June

22

June

22

Tags

Sounds Familiar: How music can evoke memories in healthy brains and in cases of neurodegeneration

Have you ever heard a song you’d forgotten about, and found yourself absentmindedly singing along? Perhaps you’re even transported back to a period in time where you listened to the song frequently, or you may recall a person or phenomenon that you closely associate with the song. Our senses (hearing, sight, smell, touch, and taste) allow us to receive information from the world around us – and whether it be the sound of a loved one’s voice, or the aroma of your favorite food, there is no doubt that our senses can also elicit specific emotional reactions. It is also undeniable that when it comes to auditory associations, society tends to pair momentous occasions in life with specific genres of music or specific songs and scores (1). This close association of a salient (striking and important) auditory stimulus with a particular event has been shown to strengthen one’s ability to encode and recall relevant memories (2). In fact, emotional memories, often those with sensory experiences intrinsically tied to them, have been found to be easier to recall than memories with no emotional component (2). Research has begun to parse how associations with sensory cues may enhance recall of specific types of memories, known as autobiographical memories.

How does the brain form memories and associations?

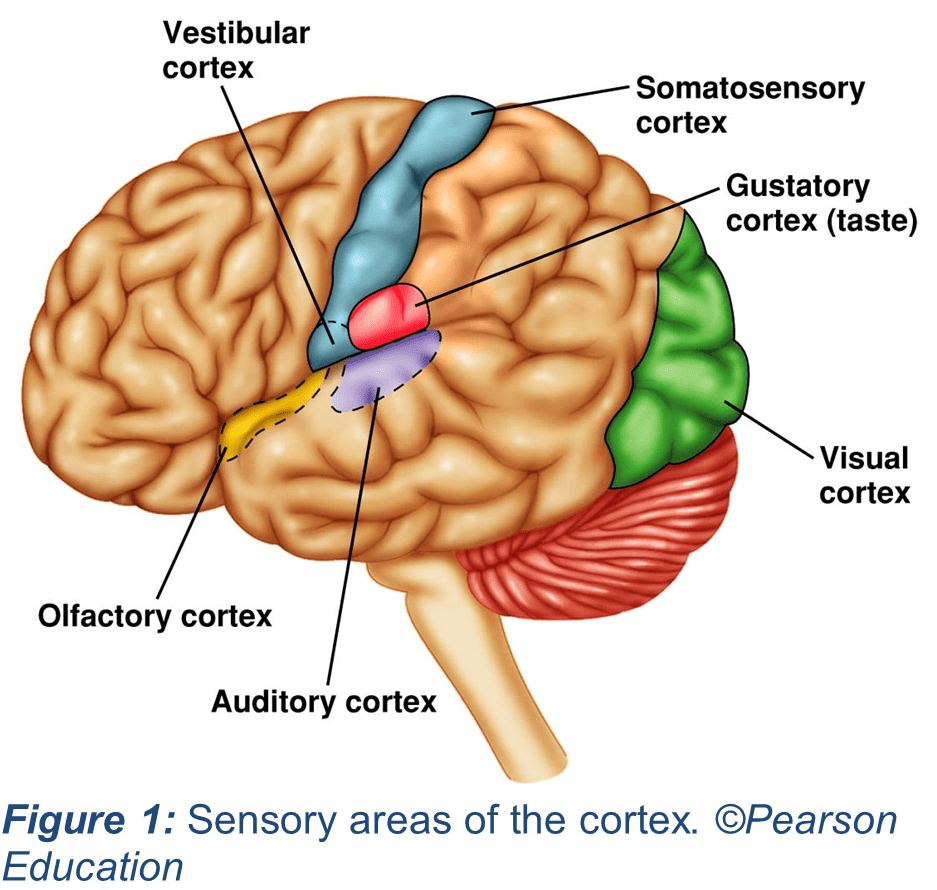

Before exploring how sensory cues can be tied to specific memories, it is important to consider the basics of how we perceive sensory information and how we form memories. For this example, imagine experiencing the rush of hearing your favorite band play a beloved song at a live event. You see them storm the stage, hear the first few notes of the opening instrumentation, and feel the vibration of the bass in your feet. All the while, your sensory processing systems are working hard to relay all this information to your brain. Specialized receptors in the skin will detect vibrotactile information and relay it from your peripheral nerves to your central nervous system, the spinal cord and brain, where it will eventually reach your cerebral cortex. The cortex is the outermost layer of your brain tissue, uniquely wrinkled with structures known as sulci and gyri to increase its surface area in primates like humans. Likewise, visual and auditory information is transmitted to specialized areas of your cortex (Figure 1).

In the brain, incoming information is learned, or encoded, by strengthening neural representations of relevant information. At the dawn of learning and memory research, a handful of neuroscience researchers helped inform the field with key principles, including Drs. Pavlov and Hebb. Ivan Pavlov, a Russian psychologist, pioneered the study of classical conditioning in dogs (you may have heard of Pavlov’s dogs; they were classically conditioned to associate the sound of a bell with their food, and would begin drooling as soon as they heard the bell ring). His work led to the observation that an association between two previously unlinked stimuli could be created by repeatedly pairing them together (3). Using this model as an example, it is not hard to imagine that semantic memory associations are also strengthened through salient (i.e., important or meaningful) associations. Semantic associations, like those formed in autobiographical memories, may be recalled with a cue much like the bell that reminds Pavlov’s dogs of their dinner; a piece of music may be tied to a specific fact, emotion, or experience. While Pavlov’s dogs’ conditioned responses can become extinct (i.e., disappear) if the bell is presented enough times without the presentation of food, our semantic associations that form autobiographical memories do not need maintenance to last.

To explore how cells in the brain work together to form associations and learn, Donald Hebb studied circuit-level neural activity. Hebb famously showed that a neuron’s repeated firing (release of electrical activity) onto another neuron strengthens their connection at the synapse (the space between two neurons). The philosophy of Hebbian learning maintains that these connections can be strengthened through consistent and causal firing patterns; in other words, neuron A must talk to neuron B consistently and cause it to fire. In the early 1990’s, notable neuroscientist Carla Shatz coined the slogan that neurons that “fire together, wire together” to simplify the phenomenon of neural connections being fortified through repeated use during Hebbian learning (4). When we recall a memory, relevant neuronal connections will fire once again, strengthening the connection and allowing us to remember.

Several regions of the brain may work together to form and encode memories. To do this, our brains convert what we observe into information that can be recalled in the future through structural and function changes in the brain (5). The brain regions that contribute to memory encoding include parts of the cortex which are separate from the areas that process incoming sensory information (noted in Fig. 1). In other words, different parts of the cortex are responsible for forming memories and for processing sensory information – it is important for a wide variety of functions. Interestingly, it is known that during the phenomenon of recalling a memory tied to sensory stimuli, parts of the cortex associated with sensory processing become active in addition to the cortical areas we typically associate with memory recall (6).

Autobiographical memories

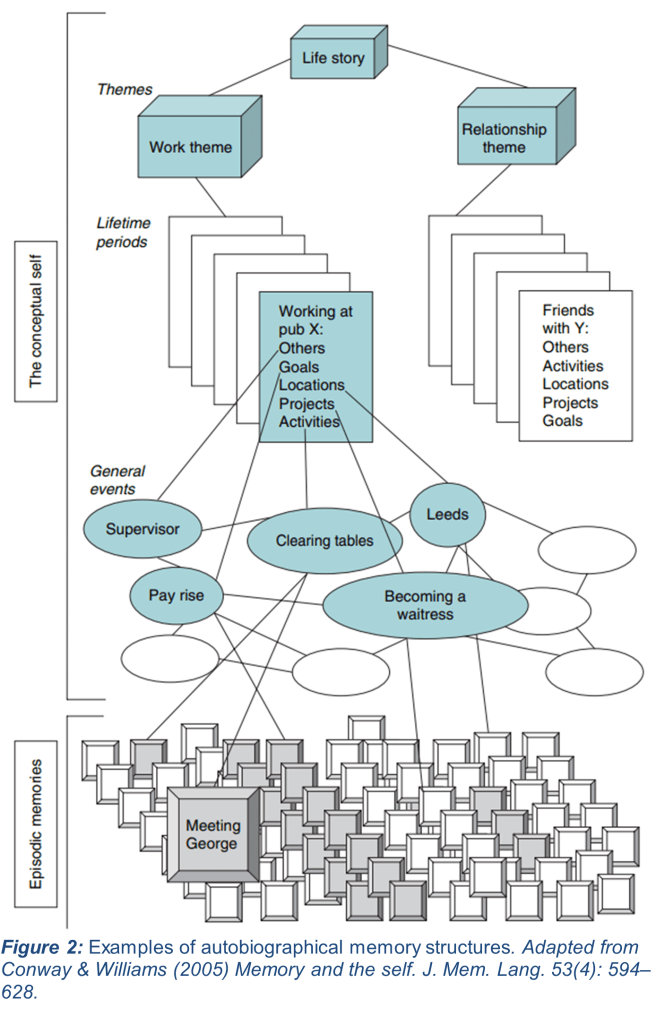

Memory, unsurprisingly, is a complicated topic. It is an umbrella term that can be parsed further into more informative subtypes. This article will focus on autobiographical memories, which are positioned between the general categories of semantic and episodic memory. Autobiographical memories are loosely defined as memories that pertain to one’s own personal history (7, 8). They can pertain to specific facts about oneself (semantics), or they may refer to the memory of specific events, or episodes, in one’s life (8). These types of information may even be intertwined (see Fig. 2 for an example of an autobiographical memory).

Some of our most salient memories pertain to ourselves and our lived experiences. The emotional aspects and individual differences in this type of memory lead to immense difficulty when trying to study its functions in a controlled laboratory environment. It is difficult to properly control external factors surrounding autobiographical memories that may influence individuals’ performance on recall tasks. As a result, there has been much more stringent research performed with semantic memory, where researchers can prod participants’ ability to recall novel, unrelated bits of information, such as a string of random words. Despite this, autobiographical memory is uniquely described as having “great feelings of vividness and rich sensory and perceptual detail,” rendering it an excellent candidate for the study of how sensory associations may affect its recall and integrity (8).

How sensory cues can elicit memories

Knowing that sensory associations can strengthen memory recall, and that autobiographical memories are some of our most vivid, researchers have begun to explore this relationship. As previously discussed, society tends to pair music with highly emotional occasions – weddings, graduations, and many more. Additionally, people in modern society tend to listen to music often and attentively, and it often evokes powerful emotional responses. For these reasons, some researchers have focused on music-evoked autobiographical memories (MEAMs) for further study.

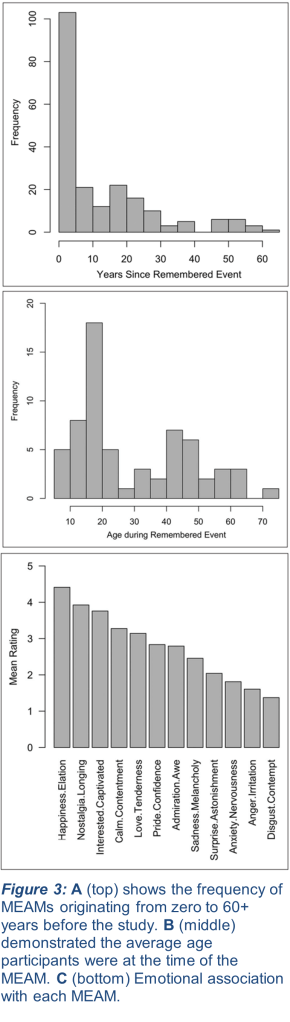

While some research has assessed the effect of MEAMs cued in a laboratory with a selection of musical pieces selected by experimenters, a team led by researchers from the Department of Music at Durham University took a different approach. To assess a more naturalistic experience, where participants would experience MEAMs in everyday life, they requested those enrolled in the study to record their music listening habits and track any MEAMs they experienced. They rated the vividness of the relevant memory, the emotion(s) it elicited, and the type of memory (be it a period of time in their life, a specific event, or a person or thing) (9). Interestingly, they found that some of their oldest participants were able to experience detailed MEAMs spanning back more than 60 years, though the frequency of recent memories for all partakers was much higher (Fig. 3A). Their finding that most MEAMs corresponded with memories from when participants were aged 10-30 also corroborates past research in laboratory environments (Fig. 3B; 10). Lastly, they received reports of a wide range of emotions tied to each MEAM (Fig. 3C). This study showcased the variability of music-evoked emotional memories, while emphasizing the prevalence of autobiographical memories cued by sensory stimuli with which individuals had forged a semantic association. Recall the Pavlov analogy here; participants’ MEAMs were created similarly to the association between the dogs’ food and the sound of a bell. Participants recalled strong autobiographical memories (the food) when exposed to a piece of music (the bell), despite the two stimuli being unrelated except by previous experience.

How music may unearth memory in cases of neurodegeneration

A topic that still perplexes neuroscientists today is neurodegeneration. While we have a better understanding of how memories are formed and preserved in the brain, as well as how this occurs in the aging brain, we still don’t know how to prevent age-related deficits in memory recall and encoding. Similar to the work done above, researchers have assessed MEAMs in those with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD, a neurodegenerative disease that leads to memory problems, and the most common cause of dementia) as well as non-AD dementia. Specifically, they assessed the second-most prominent type of non-AD dementia, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (Bv-FTD). “Frontotemporal” refers to the regions of the brain affected by this disease, the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. Bv-FTD related dysfunction in these areas leads to a loss of behavioral inhibitions (leading to a decline in ability to maintain proper behavioral conduct in social situations), as well as issues with memory (11, 12). By comparing this population to those with AD, whose frontotemporal lobes were unaffected by neurodegeneration, researchers hoped to parse differences in sensory and emotional memory recall to improve future treatment and potentially implicate specific regions of the brain in recalling MEAMs.

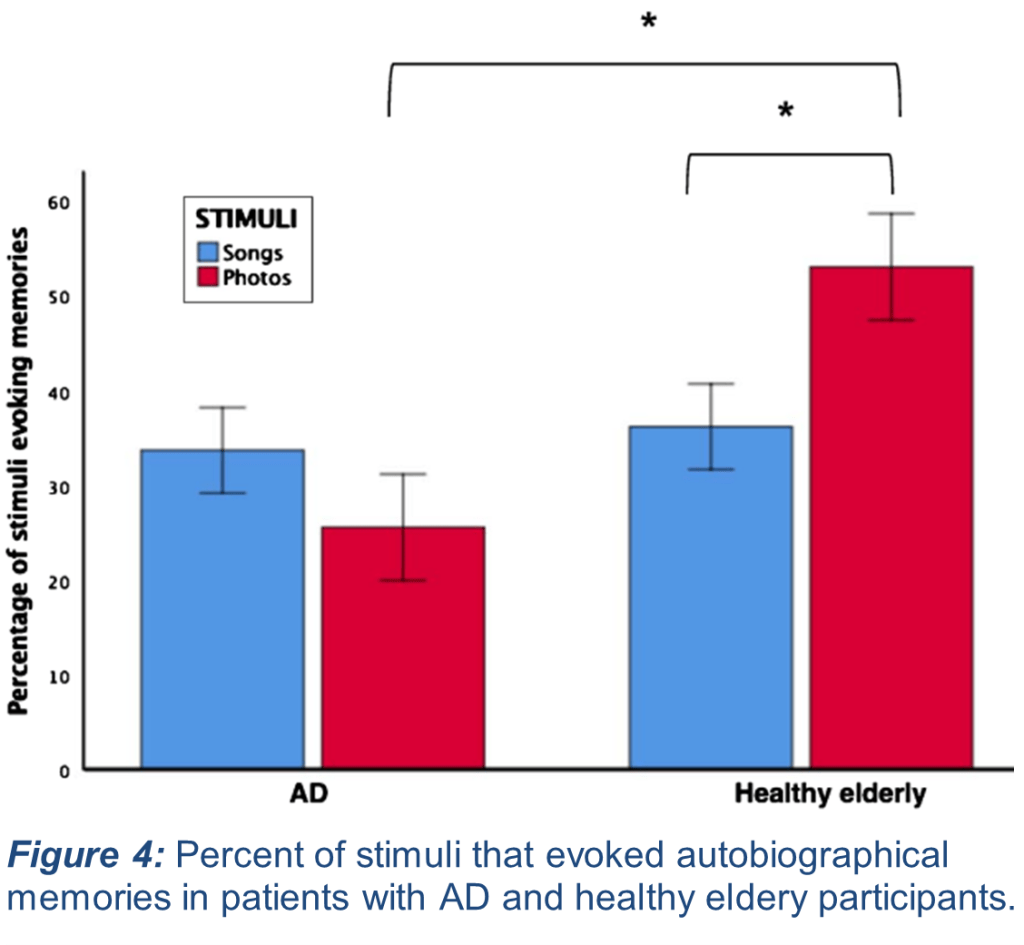

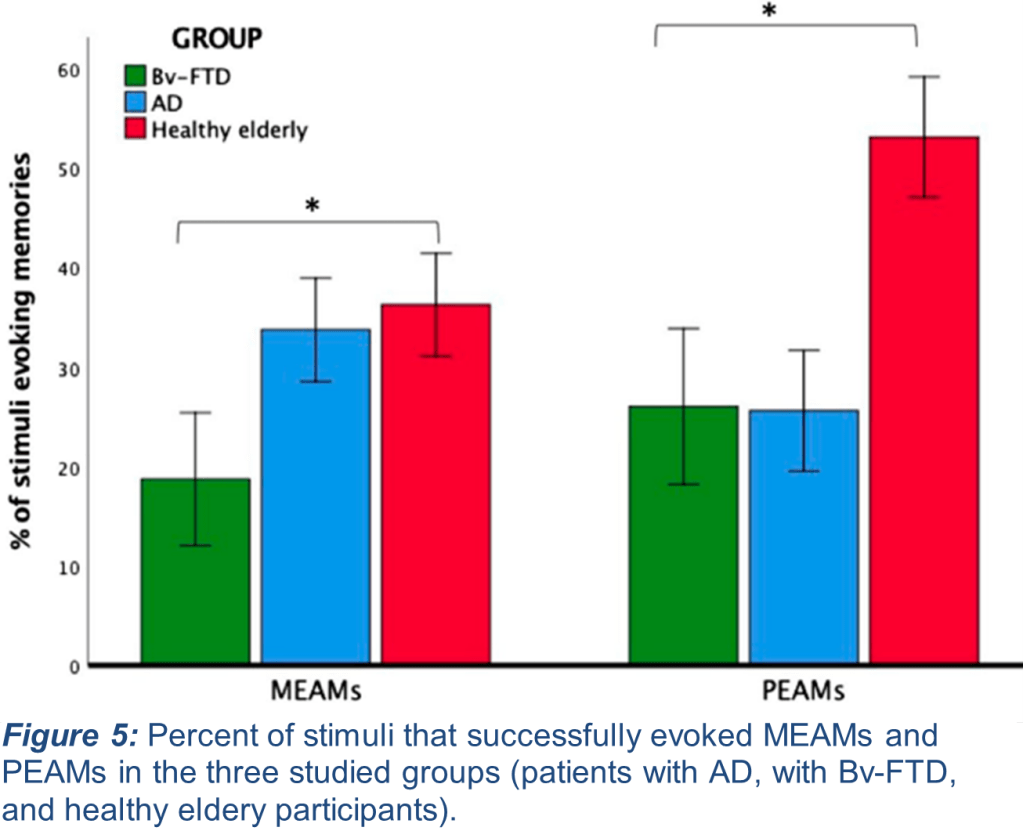

Researchers compared the frequency of MEAM recall to photograph-evoked autobiographical memories (PEAMs). In previous work, it was found that those with AD displayed a lower frequency of PEAM recall compared with healthy elderly controls, while their MEAM recall did not differ (Fig. 4). By comparing these two different sensory modalities, they hoped to further dissect the role of the same brain areas affected by Bv-FTD in specific recall of music-evoked memory. The behavior of participants with AD in this follow-up study recapitulated their prior findings, and new results indicated that participants with Bv-FTD indeed experienced significantly fewer MEAMs than did healthy controls (Fig. 5). Importantly, there was no difference in performance between those with AD and with Bv-FTD in PEAM recall. This is important because it emphasizes that the brain regions affected by Bv-FTD (the frontotemporal lobe) are necessary for MEAM recall. These findings contribute new insight into the variety of experiences those with neurodegenerative diseases persist through when attempting to recall autobiographical memories and shed light on potential strategies to better assist those with Bv-FTD in memory recall using different types of sensory stimuli as a tool.

Why this matters

Although the concept of autobiographical memories remains difficult to investigate in a laboratory environment, these studies have begun to define how MEAMs can be prompted for more naturalistic study. By proposing a role for the frontotemporal region of the brain’s cortex in recalling music-evoked memories, we may better tailor music-related interventions to patients with types of AD and non-AD dementia that will respond to these interventions, rather than attempting to use ineffective tactics to reach patients whose dementia affects necessary regions of the brain. Although there is much more work to be done, music-evoked (and other sensory-evoked) memories stand to provide interesting insight into how emotion and experience contribute to memory recall and maintenance.

References

- Merriam, A. P (1964). The anthropology of music. Northwestern University Press.

- Buchanan, T. W. (2007). Retrieval of emotional memories. Psychological Bulletin, 133(5), 761–779. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.761

- Rehman I, Mahabadi N, Sanvictores T, & Rehman, C. (2022). Classical Conditioning. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470326/

- Keysers, C., & Gazzola, V. (2014). Hebbian learning and predictive mirror neurons for actions, sensations and emotions. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 369(1644), 20130175. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0175

- Memory encoding: Memory processes storage & retrieval. The Human Memory. (2022, May 20). https://human-memory.net/memory-encoding/#Structures_serving_to_encode

- Wheeler, M. E., Petersen, S. E., & Buckner, R. L. (2000). Memory’s echo: Vivid remembering reactivates sensory-specific cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(20), 11125–11129. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.97.20.11125

- Robinson, J. A. (1976). Sampling autobiographical memory. Cognitive Psychology, 8(4), 578–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(76)90020-7

- Holland, A. C., & Kensinger, E. A. (2010). Emotion and autobiographical memory. Physics of life reviews, 7(1), 88–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plrev.2010.01.006

- Jakubowski, K., & Ghosh, A. (2021). Music-evoked autobiographical memories in Everyday Life. Psychology of Music, 49(3), 649–666. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735619888803

- Baird, A., Brancatisano, O., Gelding, R., & Thompson, W. F. (2018). Characterization of Music and Photograph Evoked Autobiographical Memories in People with Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 1–14. doi:10.3233/jad-180627

- Rascovsky, K., Hodges, J. R., Knopman, D., Mendez, M. F., Kramer, J. H., Neuhaus, J., van Swieten, J. C., Seelaar, H., Dopper, E. G., Onyike, C. U., Hillis, A. E., Josephs, K. A., Boeve, B. F., Kertesz, A., Seeley, W. W., Rankin, K. P., Johnson, J. K., Gorno-Tempini, M. L., Rosen, H., Prioleau-Latham, C. E., … Miller, B. L. (2011). Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain : a journal of neurology, 134(Pt 9), 2456–2477. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr179

- Baird, A., Brancatisano, O., Gelding, R, & Thompson, W. F. (2020). Music evoked autobiographical memories in people with behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Memory, DOI: 10.1080/09658211.2020.1713379

Pingback: The Magic of a Memory Model | NeuWrite San Diego