September

30

September

30

Tags

What Does Music Have to Do with Gender, Anyway?

When some people learn that there is research regarding the relationship between music and gender, the above is the question that is frequently uttered (and not in a nice way). However, even the very word music comes from the Greek Muses, the mythological goddesses of literature, science, and the arts (1). Likewise, the modern figurative usage of muse is a person who serves as a source of an artist’s inspiration. As people began to use muse in this way, it has generally been used to refer to a female figure or something feminine in nature. There are countless other examples of feminine characterizations of music in ancient Greece: from the legendary sirens, who lured sailors to their deaths with their enchanting voices, to women known as Hetairai, who were musically trained prostitutes that would seduce men at symposia. So, it seems that the answer to our question is a lot–music has a lot to do with gender. But do these examples show that music is inherently gendered?

Research shows that music plays a crucial part in the formation of our identity. This includes how we identify and express our gender, and these play a unique part in the formation of our identities as a whole. Moreover, music’s messages can have a significant impact on these aspects of ourselves, both positive and negative (2; 3). However, a lot of music’s influence on our identities and choices seems to be through music culture’s stereotypes and underlying messages. Faced with these facts, we are left to answer two questions: is there something about music’s structure that is inherently gendered, or is it a misogynistic society’s objectification of women as seductive beings that renders music a feminine subject? Does music culture form our identities by way of how we interact with and consume its stereotypical messages, especially concerning gender?

(Every subtitle has a link to a song related to the topic of the section, I urge you to check them out.)

The Fine Print

In two studies conducted by researchers Desmond Sergeant and Evangelos Himondes, study participants were asked how they perceived the gender of either the performer (4) or the composer (5). The subjects were experienced musicians and were asked by researchers to use the MASCFEM scale of perceived masculinity/femininity (range 1 to 14 by increasing femininity) to rate the perceived gender. Both studies made sure that there was an equally likely probability that the gender of the individual in question could be any. With regards to performers, this meant equal representation of sex/gender given the music genre/instrument; with regards to composers, this meant making it unlikely that the composer would be familiar to the listener.

The first study regarded what participants perceived as the sex/gender of the performers of a composition. There were three key findings based on the listening samples: 1) there is not an inherent quality of music structure that indicates sex/gender, 2) performers do not imbue the musical message with reliably detectable characteristics of their own sex/gender, and 3) any implications of gender by music are inferred by the listener in a subjective fashion.

Likewise, the second study regarded what the participants perceived the sex/gender of the composers of a music piece as, and this tested three different hypotheses. The following are the conclusions this study came to: 1) nothing in the composition of music infers sex/gender, and 2) the perception of the gendering of music is not related to the sex of the listener. The final hypothesis–that musical sounds, or the organization of sounds within a composition, infer sex or gender characteristics–was actually found to be true. However, researchers further analyzed the results and believe that this is likely caused by the gender stereotypes the listeners inferred. Based on the results of the two studies, Sergeant and Himondes came to one important conclusion: “[T]he scope of [these] studies pertains not to musicology, but to psychology.”

So we come to a possible answer to our first question: no, music does not have any inherent relation to gender. However, to get a more holistic view of music’s relation to gender, we also need to answer our second question: what of music culture’s influence on our identities through the stereotypes it conveys?

All My Best Friends are Metalheads

As it seems, a lot of recent research has found what an important part music plays in the formation of our identities (6). We use music to express ourselves and explore our identities. It helps us decide who we are and what we aspire to be by supporting the exploration and integration of our identities. Additionally, we can use music to aid in expressing these identities to others. We use music both consciously and unconsciously to demonstrate our attitudes, values, and beliefs. It also is how we can know who others are.

If we take into account how music is such an integral part of our lives, it only makes sense that it contributes to the formation of our gender identities and expression as well. Feminist scholars have researched gender’s relation to music and have concluded that the two do seem to have a link that is baked into the culture surrounding music, via stereotypes and listeners’ biases (7; 8). Interestingly, it seems most mention of women in music in ancient Greece was in relation to their seductive nature, rather than musical talent (9; 10). Most of the stories from Greek mythology are of feminine creatures that use music to seduce people to get what they want. Even in modern music culture, there are many misogynistic messages and connections between “woman” and “seductive”. Gender stereotypes run amuck in modern music culture (3; 11; 12). Think of the examples from ancient Greece mentioned before, where feminine and seductive themes are intertwined with music culture, from the myth of sirens to the very real, seductive Hetairai.

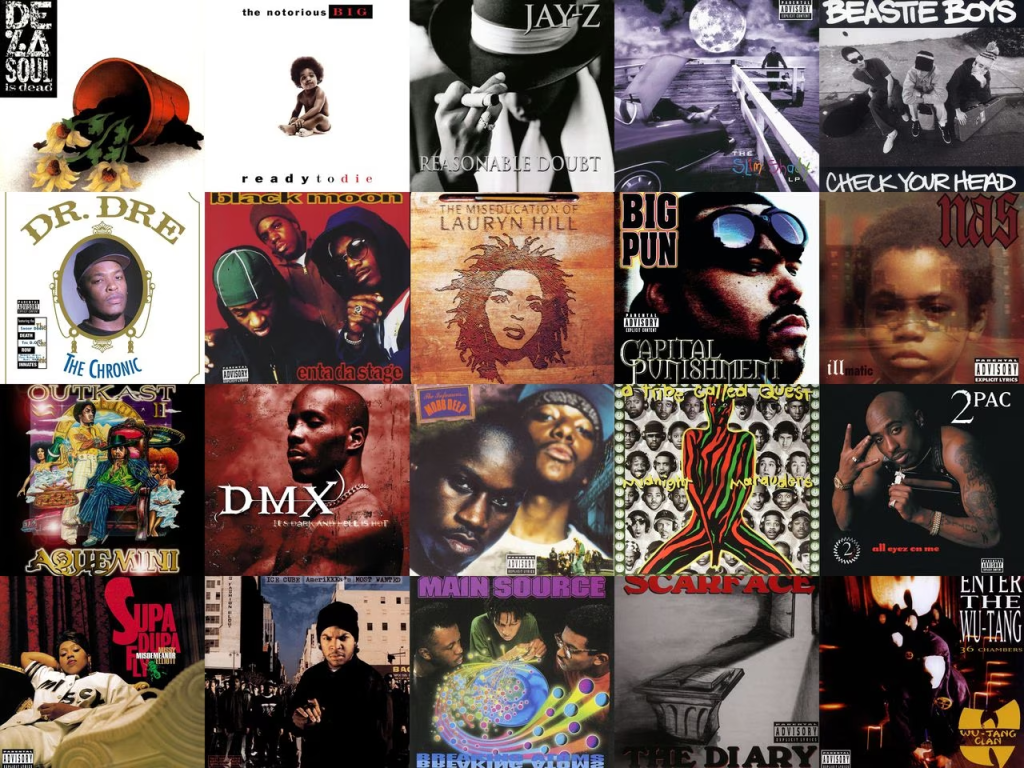

Detractors, however, criticize those who research the connection between gender and music by claiming “…that gender studies and gender equality politics have gone ‘too far’ and may even be a conspiracy”, or that “…research should be separated from political thought [so that it] can be objective.” (11). Yet, author Ann Werner states, there seems to be a lot of research focused on how youth interact with music based on their gender, already. This, like most things in our society, unfortunately, is biased towards studies of young men. Although research was not to elucidate music’s connection to gender, studies in the past regarding media consumption have factored in gender. Werner notes how public debate in the past focused on topics such as how heavy metal bands were seductive and destructive to young girls in the 1980s and how hip-hop of the 1990s “destroyed” black North American youth because it was viewed as misogynistic and violent (11).

However, this was public debate–which only looked at biased consumer trends and stereotypes of music consumption–not formal research. We have since realized that music can actually have important, and sometimes disastrous, effects on how we view ourselves, through research. In today’s society, much of our media and music is heteronormative–i.e. it assumes the consumer is heterosexual and cisgender (i.e. identify with one’s biological sex). Although there certainly can be negative consequences of music’s influences on heterosexual and cisgender individuals, music may be especially damaging to the development of those in the LGBTQ+ community because of its heteronormative nature (3). This is because, as some researchers point out, music can “change the way people feel about themselves or even understand themselves” (3). Thus, music that contains homophobic or transphobic messages may have serious consequences on an individual’s development of their sense of self and/or mental health (3).

MASCULINITY

Children also learn to express their genders through what is known as “gender-typing”: because there are gender stereotypes based on the biological, children infuse what is appropriate for them into who they are based on their biological sex (12). Since music is generally regarded as a ‘feminine’ subject for kids in school, children absorb these gender stereotypes through gender-typing, and we see marked differences regarding what instruments children play based on gender.

One way gender-typing seems to play a role in music is how we expect children to interact with music (Yes, there are gender stereotypes regarding what gender should play a particular instrument). In one study, the specific gender differences in instrument preference were studied, and research on children 9 to 10 years old found that boys were more likely to prefer instruments such as drums, guitars, and trumpets, whereas girls were more likely to prefer flute, piano, and violin (12); although recently, researchers have found this trend is changing due to the introduction of music technology in classrooms, such as drums and electronic instruments.

However, these stereotypes seem to only matter at certain ages: younger children seemed to have no differences in the instruments they preferred, regardless of gender stereotypes (in this study, “young” was defined as age 5 years old). However, children aged 10 years old did show a significant difference in instrument choice (12). Although gender typing plays a big role in children conforming to these stereotypes of their own accord, there is also evidence from these studies that parents may be encouraging their children to choose the instruments due to their ideas of gender stereotypes. Gurl, just let the music play.

Rebels

I hope that you now can see how much music and gender are linked; or rather, how much we have made it about gender. As the final study shows, nothing in the performance or composition of a music piece reliably infer gender. However, in some of the studies mentioned, it’s clear that some people want music to infer gender, and the gender stereotypes abound in music exemplify that. Although music doesn’t inherently have anything to do with gender, music in the context of gender has already been studied for decades. Nevertheless, just because music doesn’t inherently have anything to do with gender doesn’t mean that it can’t be connected in a meaningful way. Music undeniably aids in identity formation. Music can help people going through hard times, such as those in the LGBTQ+ community, and those experiencing gender dysphoria. It can help people explore their gender and form their gender identity. Music can even help people become aware of and express their gender.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muses

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0305735613515943

- https://www.proquest.com/openview/04587c7ff0900863184b5483b876205a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3997045/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4815278/

- https://books.openbookpublishers.com/10.11647/obp.0292.pdf

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/popular-music/article/broadening-research-in-gender-and-music-practice/179D11BF93D57C3CB069F6ED51D673BD

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00411/full

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/jnr.25175

- https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/culture-magazines/women-ancient-music

- https://periodicos.ufmg.br/index.php/permusi/article/view/5266/11910

- https://6jornadesmusicologia.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/nicola-dibben.pdf

You must be logged in to post a comment.