November

07

November

07

Tags

A Biological Time Machine

Time is a paradox; it’s both simple and complex. On the one hand—in its most literal form—time is linear, methodical, unidirectional, and can be measured in well-defined units. On the other hand, or hands, it is warped—circular even—multidimensional, and scalar, among many other properties that constitute a sometimes exciting, sometimes saddening, and sometimes maddening concept, idea, thing. An intangible thing, yet palpable, as moments of joy, love, excitement, grief, or disappointment pass us by. During these intense moments, or really after they’ve passed, we feel time, or at least perceive the feeling of it. In our bones, in our hearts, and in our brains. The passing of these moments creates a desire to relive them and all the magical feelings that accompany them. As a species, we have searched for solutions to satisfy this desire for thousands of years. From Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China, to contemporary billionaires in Silicon Valley, and so many in between, we have been searching for a solution, whether that be a fountain or a pill, to mortality—to experiencing these precious moments forever (Britannica; Tech Review). Until now, only science fiction could provide a solution.

A potential solution was born in 2006 from the revolutionary discovery of what are now called the Yamanaka Factors (Takahashi & Yamanaka, 2006). Now, you might be asking yourself, “Huh? Yamanaka Factors?” So, let’s start with some basics. The Yamanaka Factors (YFs) are named after Shinya Yamanaka, whose lab discovered factors for cellular reprogramming, a process in which an adult cell reverts to a stem cell. A stem cell is an immature cell that can differentiate into any cell type: a cell in your liver, in your skeletal muscle, in your brain, etc. How the YFs reprogram mature cells into undifferentiated baby cells is still not completely understood.

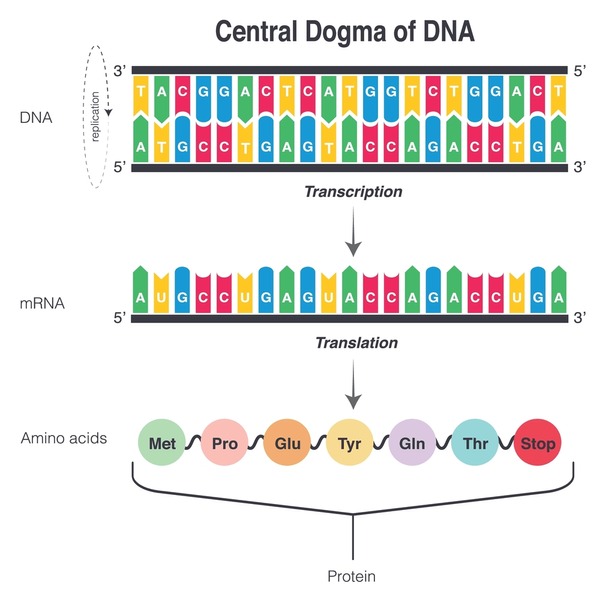

Your DNA is many long lists of letters—four letters, ATGC, to be exact—packaged into many different shapes and structures called chromatin conformations. Particular patterns of letters in our DNA represent specific genes. Genes are “read” into an intermediary strand of more letters called RNA. RNA strands are then “read” again by a biological machine—ribosomes—to make proteins. This process is called the Central Dogma of DNA (Figure 1). And these proteins do everything in your body from “reading” your genes to breaking down the nutrients you eat to building the cells that constitute your heart, veins, bones, neurons, and everything else in your body. This process is called gene expression, and there are many ways to regulate it. The YFs are believed to control processes that occur before the first “reading” of a gene, by changing the shape of chromatin, adding/removing chemical groups to/from DNA, and recruiting the gene “readers,” among other proposed mechanisms (Cipriano et al., 2024). DNA methylation is one of the most influential processes through which the YFs act. DNA methylation is the addition of a methyl group (-CH3) to certain letters on DNA. Conventionally, when methyl groups are added to a gene, it prevents gene expression. And when methyl groups are removed, the gene can then be expressed. The maintenance of proper DNA methylation patterns has proven to be important, evidenced by irregular patterns in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and aging (Kane & Sinclair, 2019). In fact, DNA methylation has become somewhat of a gold standard for measuring biological age of a cell and organism (Horvath, 2013). Got it? Good.

To discover the YFs, Yamanaka’s group curated a list of 24 genes known to help maintain a stem cell state. These scientists believed that some of these stem cell maintenance genes could also revert an adult cell to a stem cell. In other words, reverse the cell’s age. They whittled down their list of 24 by first inserting all 24 genes into an adult mouse cell to see if it would revert to a stem cell. And it worked; they could reverse the age of a cell! From there, they removed genes one at a time, observing which genes’ removal caused the adult cell to remain an adult and, therefore, signifying its importance to stem cell induction. Eventually, they shrank their list to four genes. They then tried inserting different combinations of these genes and found that inserting all four was the most effective combination (Takahashi & Yamanaka, 2006). And with that, the Yamanaka Factors—and a potential biological time machine—were born. Showing that the YFs were relevant and potentially applicable to humans as well, Yamanaka and his team reprogrammed adult human cells in a dish to stem cells with the insertion of the same four genes (Takahashi et al., 2007).

So, researchers found the solution to immortality, right? We can just express the YFs in our bodies and never grow old? Not quite. These first experiments were conducted in cells living in a dish—a model far from a highly evolved organism with many organs made up of thousands of cell types, all communicating through several modalities. Researchers have, however, demonstrated that the YFs can prevent several age-related deficits in mice.

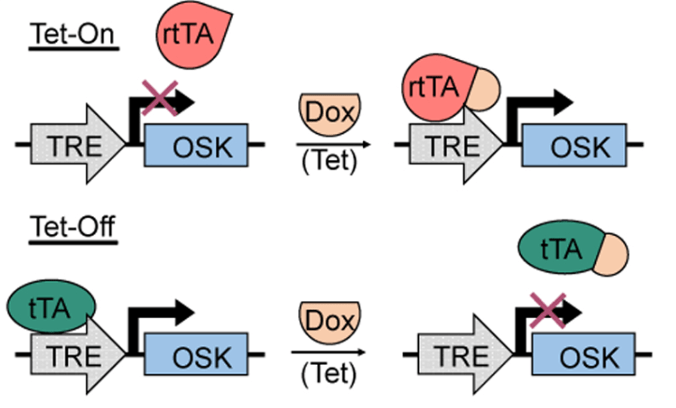

Before moving onto the experiments, let’s establish an important method that will be used throughout the studies: the Tet-On/Tet-Off systems (Figure 2). These systems allow researchers to control the expression of their genes of interest. In the Tet-On system, a synthetic transcription factor (rtTA), whose ability to bind to DNA requires first binding to a drug called doxycycline (Dox), is introduced into a cell. Then another set of genes are introduced into that same cell, and they are only expressed when the transcription factor is bound to Dox and, therefore, able to facilitate the “reading” of the genes of interest. In the Tet-Off system, the transcription factor (tTA) is slightly modified so that it can bind DNA in the absence of Dox, and when Dox is present, it cannot, effectively turning off the expression of the gene(s) of interest (Lu et al., 2020). These designs allow researchers to induce and stop the expression of genes of interest simply by giving mice doxycycline, typically in their drinking water. With this method down, let’s move onto the fun part.

When researchers initially induced YF expression in living mice, they observed high mortality rates and tumors throughout the body due to mass cellular dedifferentiation. To prevent these outcomes, they shortened the duration of YF expression, resulting in partial reprogramming of cells and, consequently, preventing mass dedifferentiation and tumor formation (Abad et al., 2013; Ohnishi et al., 2014). With these problems solved, several groups have used the YFs to turn back the biological clock and started trying to solve some of the biggest age-related phenomena in mouse models.

Everyone experiences age-related cognitive decline to some extent, and it is one of the hardest things to accept and deal with as we age. The YFs may be able to help with this menacing inevitability. Using Tet-On in a subpopulation of excitatory neurons in the brain, scientists treated mature adult mice with Dox three days a week for six months, at which point the mice performed three behavioral tests for anxiety, short-term memory, and spatial memory. In contrast to untreated mice, the YF mice performed significantly better in all three tests. Consistently, genes involved in nervous system development, regulation, and plasticity were enriched in the YF mice compared to normally aged mice (Antón-Fernández et al., 2024). While this study could have been improved by conducting baseline behavioral tests or comparing the aged YF mice to healthy young mice to see if cognitive decline could be reversed, it did show that cyclical YF expression could improve cognitive abilities relative to age-matched controls. It will be interesting to see if these results can be reproduced in models of neurodegeneration, in addition to normal brain aging.

Another age-related issue we face is vision loss. Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) causes irreversible blindness and affects nearly 200 million people worldwide. Mice also lose vision with age, although in a different way than AMD, and the YFs have been shown to prevent this effect. After only four weeks of cyclical YF expression, the visual abilities of aged mice did not change while their age-matched controls declined significantly, as measured by a visual acuity task and electroretinograms. Not only did YF expression prevent age-related vision loss, but it also reversed vision loss caused in a mouse model of glaucoma, a leading cause of blindness due to increased intraocular pressure, and regenerated the optic nerve after complete severance (Figure 2) (Lu et al., 2020).

Another incredible demonstration of the YFs ability to partially reprogram cells to a younger state and improve health outcomes was shown in a mouse model of Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS). In humans, HGPS causes premature aging, with the average lifespan being 14.5 years, due to a mutation in the protein Lamin A, which has a number of functions related to chromatin organization, accessibility, and stability (Kane & Sinclair, 2019). Amazingly, cyclical treatment with Dox improved spine curvature, intestinal architecture, epidermal thickness, spleen shrinkage, kidney atrophy, and epithelial thinning in the stomach, among other mouse HGPS hallmarks, compared to untreated HGPS mice. Preventing these age-related symptoms likely contributed to the 9-week extension of maximum lifespan seen in the YF/HGPS mice. HGPS mice that typically die in about 21 weeks lived to 30 weeks—a 43% increase in lifespan (Ocampo et al., 2016). Even inhealthy mice, cyclical YF expression, starting in the human equivalent of our 80s, extended the maximum lifespan by 10 weeks compared to untreated mice—almost a decade in human years (Macip et al., 2024).

What do all of these results mean? The YFs produce a consistent story: we can slow down, prevent, and even reverse some of the most debilitating hallmarks of aging. In mice. With additional studies in mice, non-human primates, and, of course, humans, it is not unreasonable to think that we could someday drink doxycycline starting at the age of 30 and extend our healthspan and lifespan for a significant amount of time. We could stave off certain cancers, neurodegenerative diseases, vision loss, metabolic disease, frailty—the list goes on! And why shouldn’t we? Living in a world without these ailments sounds a hell of a lot better than one where we continue to accept the inevitable decline that comes with time.

So, I ask again: why shouldn’t we aim to extend our lifespans? Among the myriad of moral and ethical considerations, perhaps the answer lies in the wisdom of Ferris Bueller, “Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.” In such a simple way, he alludes to the most important properties of time and the paradox they create. Time—our time—is fleeting, finite, and unstoppable. The paradox is that these properties add beauty and meaning to our lives but create fear of running out of time to experience that beauty, making us want more time. But if we had more time, we might not experience the same beauty. What if Ferris Bueller had said, “Don’t worry about missing out. You’ve got an eternity to experience it.”? Now, imagine a simple pleasure: watching the sun slip behind a mountain range, hugging a friend, eating your favorite meal. Do you see the soft light of the sun? Do you feel the warmth of the hug? Can you taste the salt? Feel the beauty of each moment. Now imagine you could experience moments like those forever. Would they still be as beautiful?

References

Abad, M., Mosteiro, L., Pantoja, C., Cañamero, M., Rayon, T., Ors, I., Graña, O., Megías, D., Domínguez, O., Martínez, D., Manzanares, M., Ortega, S., & Serrano, M. (2013). Reprogramming in vivo produces teratomas and iPS cells with totipotency features. Nature, 502(7471), 340–345. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12586

Antón-Fernández, A., Roldán-Lázaro, M., Vallés-Saiz, L., Ávila, J., & Hernández, F. (2024). In vivo cyclic overexpression of Yamanaka factors restricted to neurons reverses age-associated phenotypes and enhances memory performance. Communications Biology, 7(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06328-w

Cipriano, A., Moqri, M., Maybury-Lewis, S. Y., Rogers-Hammond, R., de Jong, T. A., Parker, A., Rasouli, S., Schöler, H. R., Sinclair, D. A., & Sebastiano, V. (2024). Mechanisms, pathways and strategies for rejuvenation through epigenetic reprogramming. Nature Aging, 4(1), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-023-00539-2

Horvath, S. (2013). DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biology, 14(10), 3156. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115

Kane, A. E., & Sinclair, D. A. (2019). Epigenetic changes during aging and their reprogramming potential. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 54(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409238.2019.1570075

Lu, Y., Brommer, B., Tian, X., Krishnan, A., Meer, M., Wang, C., Vera, D. L., Zeng, Q., Yu, D., Bonkowski, M. S., Yang, J.-H., Zhou, S., Hoffmann, E. M., Karg, M. M., Schultz, M. B., Kane, A. E., Davidsohn, N., Korobkina, E., Chwalek, K., … Sinclair, D. A. (2020). Reprogramming to recover youthful epigenetic information and restore vision. Nature, 588(7836), 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2975-4

Macip, C. C., Hasan, R., Hoznek, V., Kim, J., Lu, Y. R., Louis E Metzger, I. V., Sethna, S., & Davidsohn, N. (2024). Gene Therapy-Mediated Partial Reprogramming Extends Lifespan and Reverses Age-Related Changes in Aged Mice. Cellular Reprogramming, 26(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1089/cell.2023.0072

Ocampo, A., Reddy, P., Martinez-Redondo, P., Platero-Luengo, A., Hatanaka, F., Hishida, T., Li, M., Lam, D., Kurita, M., Beyret, E., Araoka, T., Vazquez-Ferrer, E., Donoso, D., Roman, J. L., Xu, J., Esteban, C. R., Nuñez, G., Delicado, E. N., Campistol, J. M., … Belmonte, J. C. I. (2016). In Vivo Amelioration of Age-Associated Hallmarks by Partial Reprogramming. Cell, 167(7), 1719-1733.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.052

Ohnishi, K., Semi, K., Yamamoto, T., Shimizu, M., Tanaka, A., Mitsunaga, K., Okita, K., Osafune, K., Arioka, Y., Maeda, T., Soejima, H., Moriwaki, H., Yamanaka, S., Woltjen, K., & Yamada, Y. (2014). Premature Termination of Reprogramming In Vivo Leads to Cancer Development through Altered Epigenetic Regulation. Cell, 156(4), 663–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.005

Takahashi, K., Tanabe, K., Ohnuki, M., Narita, M., Ichisaka, T., Tomoda, K., & Yamanaka, S. (2007). Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors. Cell, 131(5), 861–872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019

Takahashi, K., & Yamanaka, S. (2006). Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors. Cell, 126(4), 663–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024

You must be logged in to post a comment.