December

19

December

19

Tags

A 3D Camera for the Brain: The Simplified Science of MRI

Have you ever dreamed of having Superman’s power of “X-Ray Vision,” or the ability to see through solid objects? While it is uncertain if this superpower was their motivation, medical researchers and physical scientists in the 1970s were able to turn this dream into a sort of reality with the invention of the MRI scan [1].

MRI is a non-invasive method used by physicians and scientists to gain insight into the structure and function of internal organs, often to help determine the root of unexplained symptoms like chronic headaches or seizures. This procedure can sound pretty scary if you’ve never had one before, and it is common to have questions about not only how safe of a procedure it is, but what exactly is happening in the body during an MRI. Let’s talk about it!

What is an MRI?

MRI stands for magnetic resonance imaging, which means that the machine uses magnetic fields and the principle of resonance (a type of atomic spinning, detailed later) to create an image. Simply put, an MRI scanner is a magnet – a big, loud, donut-shaped magnet (Figure 1). Each MRI scanner uses a specific magnetic field, the strength of which is measured in units called “Teslas” (often just labeled as “T”). Stronger MRI scanners have an increased Tesla range, and thus can parse out smaller differences in resonance – so the higher the Tesla of the scanner, the better the image resolution. Typically, clinical MRI scanners come in 1.5T or 3T variations, with the world’s most powerful human scanner to date at 11.7T [3]. This machine acts as a 3D camera, and takes pictures of soft tissues like the brain or the spinal cord that are not visible in other forms of imaging when bones get in the way, such as a traditional X-ray scan. Perhaps Superman’s power should be renamed “MRI Vision.”

What is resonance?

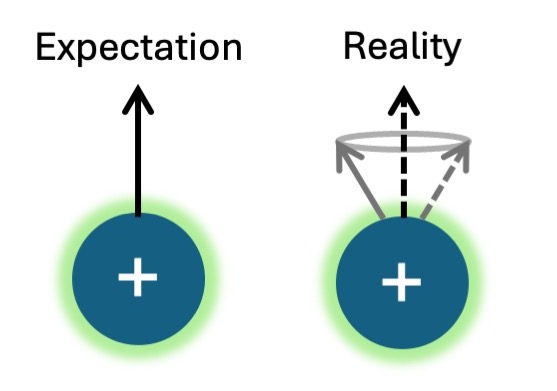

To understand resonance, we must first understand protons. Protons are the positively charged particles in an atom, and at rest, they face random directions. When protons are exposed to a magnetic field, they will turn to face the negative side of the field. However, protons are not as perfectly symmetrical as one might think, and this lop-sidedness (among other things, read more here [4]) causes the protons to spin around the intended direction rather than facing it directly (Figure 2). For simplicity, the direction of the proton is generally considered to be the direction that it spins around (or “intends” to face), rather than the exact direction based on its phase of spinning at a given time.

In the world of MRI, resonance is often referred to as the “wobble” of a proton, or the rate of this spinning. Resonance is typically measured from atoms that are not constrained by bonds in complex molecules since these bonds can affect the proton’s ability to spin naturally, thus reducing or altering the signal. The nucleus of a hydrogen atom contains a single proton, and free hydrogen atoms are abundant in both water and fat in the body. As such, hydrogen is generally the target atom of MRI scans. The resonance behavior of hydrogen is well established, and most MRI scanners are calibrated to target hydrogen protons specifically [5].

How does an MRI work?

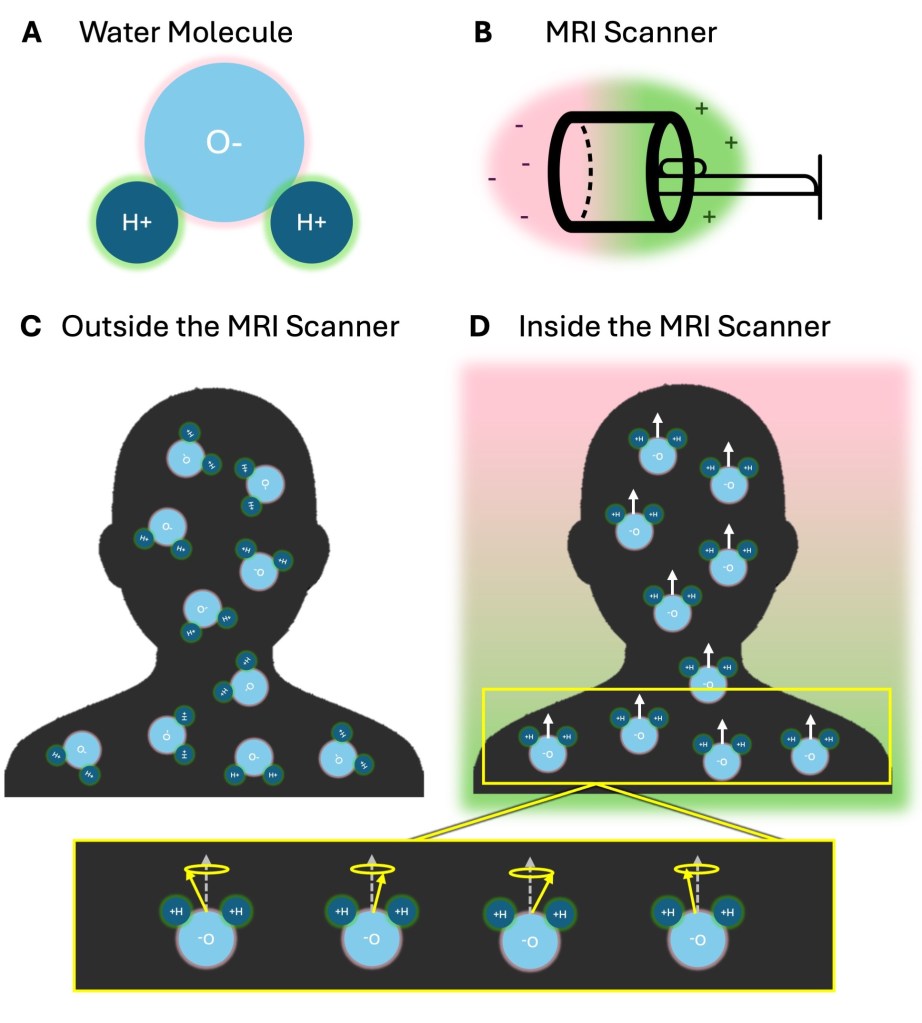

So how does this idea of resonance and strong magnetic fields come together to create pictures? To answer this question, let’s consider a water molecule (Figure 3a). Water is made up of three atoms: two hydrogens and one oxygen. In this molecule, the hydrogen atoms are positively charged and the oxygen atom is negatively charged. When water molecules are exposed to a magnetic field, the side with the positive hydrogens will turn to face the negative charge, and the negative oxygen atoms will face the positive charge.

You can think of an MRI scanner like a battery – with one side more positively charged (the green side in Figure 3b) and the other more negatively charged (the pink side in Figure 3b). Typically water molecules face random directions in the body (Figure 3c), however upon entering the scanner, all the positive hydrogen atoms will align to the magnetic field of the scanner, causing the whole water molecule to face the negative (pink) side (Figure 3d). Since only the direction of the molecule was changed at this point, all protons will be resonating at their natural frequency (as shown in yellow).

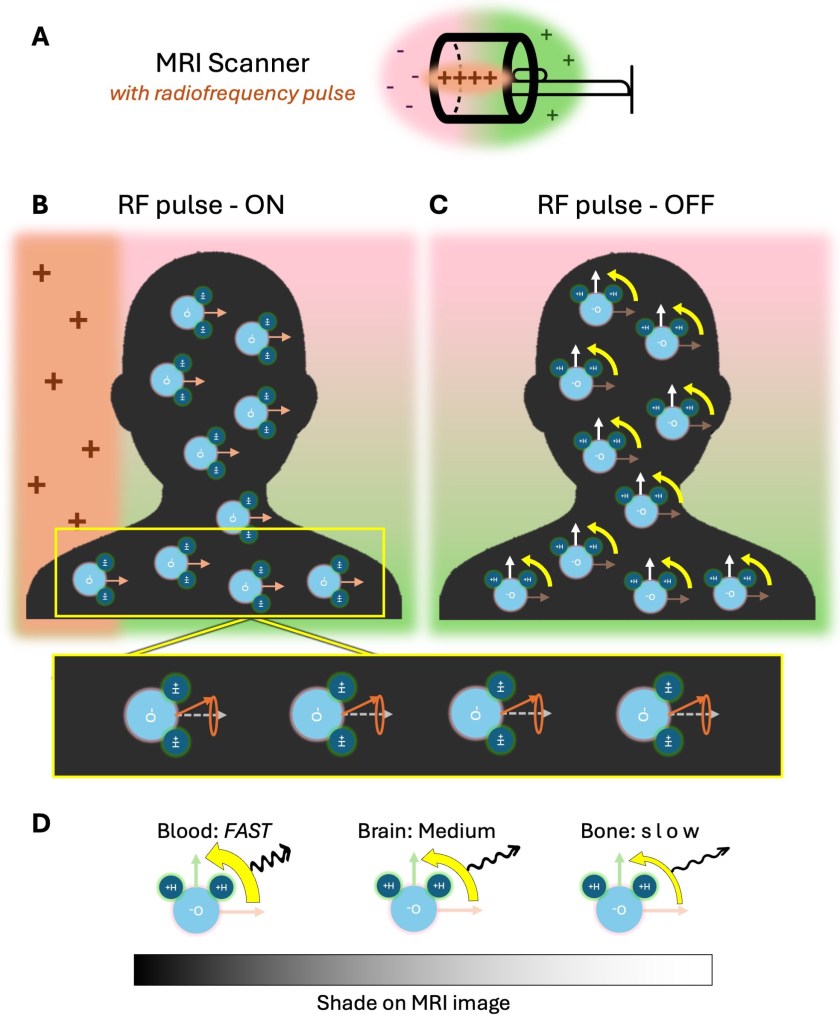

During an MRI, the scanner makes a rhythmic beating sound. This sound is a second magnetic field, called a radiofrequency (RF) pulse, being turned on and off (positive side shown as orange in Figure 4a). When this second field is on, the water molecules will align to the new direction. This RF pulse is set at a specific frequency that throws off the natural spin pattern of the protons, and causes them all to spin in phase with each other (Figure 4b) [6]. This second field is quickly turned off, and the water molecules return to face the original negative side of the scanner (Figure 4c). When water molecules perform this realignment, protons also return to their natural resonance. In doing so, the protons release a specific amount of energy dependent on how much the RF pulse frequency altered their natural resonance pattern. This energy is released in the form of a radio wave that can be measured by receivers in the scanner, the same way that a car receives radio signals to play music. Since tissues in the body have varying amounts of water, they release different amounts of energy. These small differences are picked up by the scanner, similar to a car system picking up FM 101 versus FM 102, and show up on the MRI image as different shades of gray (Figure 4d). For instance, water molecules are extremely abundant in the blood, so high levels of energy are released from areas like blood vessels or around the heart. These high-energy areas are typically represented with darker shades on an MRI scan image, but can vary by the type of scan. Organ or muscle tissue, on the other hand, contains less water, and will release less energy during realignment. These areas typically show up as lighter on an MRI scan [2, 7].

How can this be safe?

MRI scans are one of the safest medical procedures available [8].There are magnets all around us, from junkyard magnets used to lift cars (with a strength of ~1T), to the souvenir magnet on your fridge (~0.005T), to the magnetic pull of the north and south pole (~5 x 10-5 T) [9]. While the magnetic strength of an MRI scanner is much higher, extensive research has been done to confirm that there are no harmful effects of this strong magnetic field on the body. In this way, MRIs are actually much safer than other techniques used to image the human body, such as x-rays (which involve radiation risks) PET scans (which require chemicals called “contrast agents” to be injected to the bloodstream). Even the proton realignment is completely harmless- in the same way that you generally cannot feel blood moving in your body, you cannot feel water molecules changing directions either.

The only way in which the magnet strength poses a safety risk is if metallic objects are brought near the scanner, as the strong magnetic pull can cause these objects to fly into the center of the magnetic field at high speeds. This risk is why everyone entering rooms with MRI scanners is thoroughly screened for any metal, such as piercings or medical implants, multiple times and often before even entering the building.

Realistically, the biggest safety concern for most patients receiving an MRI scan is the exposure to loud sounds made by the scanner which, without earplugs, can cause hearing damage [10]. MRI scanners emit around 100 decibels of noise (ranging from 65-130), which is comparable to the noise level of a rock concert or a chainsaw [11]. Layered ear protection such as earplugs, headphones, and even foam padding around the head is the standard to help reduce exposure to this noise during the scan. Another safety concern often noted is the potential for heating [10]. The energy released when protons perform their realignment can cause conductive materials to heat up rather quickly, and in extreme cases of highly conductive materials, even cause burns. Most of the time however, this heating will be a harmless feeling of tingling or itching. This effect can be slightly amplified in materials with metallic components even if they are not inherently metal, such as the ink in some tattoos or reflective athletic clothes.

Overall, MRI scans are a safe and effective procedure to determine the structure and function of various organs inside the body in a non-invasive way. If the physics did not convince you that MRI scans are as cool as Superman’s “X-Ray Vision,” maybe this structural MRI scan showing the author of this article’s brain will!

References

[1] National Science Foundation Impacts Website. MRI: Imaging Living Tissue. https://new.nsf.gov/impacts/mri

[2] P. Lam (2023) What to know about MRI Scans. Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/146309#what-is-an-mri-scan

[3] Commissariat à l’énergie atomique et aux énergies alternatives (CEA) (2024) 11.7 Tesla: First images from the world’s most powerful MRI scanner. Healthcare in Europe News. https://healthcare-in-europe.com/en/news/11-7-tesla-first-images-world-most-powerful-mri-scanner.html

[4] E. Siegel (2017) Why Does The Proton Spin? Physics Holds A Surprising Answer. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/startswithabang/2017/04/19/why-does-the-proton-spin-physics-holds-a-surprising-answer/

[5] J.T. Bushberg et al. (2011) Essential Physics of Medical Imaging. Wolters Kluwer Health. https://www.ebrain.pitt.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/2020-01-10-mri-basics.pdf

[6] A. Berger. (2002) Magnetic Resonance Imaging. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7328.35

[8] NHS Inform Website. MRI Scan. https://www.nhsinform.scot/tests-and-treatments/scans-and-x-rays/mri-scan/

[9] Questions and Answers in MRI. (2024) How Strong is 30T? https://mriquestions.com/how-strong-is-30t.html#/

[10] S. Keevil. (2016) Safety in MRI. Medical Physics International. http://mpijournal.org/pdf/2016-01/MPI-2016-01-p026.pdf

[11] Envision Radiology. Noises to expect during an MRI. https://www.envrad.com/noises-to-expect-during-an-mri/

You must be logged in to post a comment.