January

16

January

16

Tags

Under Your Skin: the Immune Science Behind Tattoos

The skin is the first major barrier to injury and harm in everyday life. In areas where clothes or hats fail to protect us, our skin protects us from the sun’s harsh UV rays. If we trip and fall, we might receive mere scrapes to the skin while our muscles and bones will remain unscathed. If one spills, say, hot coffee on themselves when they trip, it is our skin protecting everything underneath from harm. In addition to being our largest organ and protecting us from a myriad of foreign materials, our skin is teeming with helpful immune cells which are always at the ready to eliminate external threats that may enter our system when the outer layer of our skin becomes compromised. Most of the time, our skin heals from a cut or scrape with no sign of prior injury. So, what exactly happens when we decide to adorn our skin with permanent inky pops of personality – tattoos?

Tattoos have been a part of society for thousands of years. They are a traditional practice in many cultures, such as the Māori people [1]. In modern times, they are seen as a form of creativity and self-expression. At many points in history, they have also been associated with negative parts of society. Opinions and experiences with tattoos are as unique as the works themselves. Less numerous, but also in great variety, are the methods for creating tattoos. Whether it be manual or mechanical, every method has the common goal of delivering permanent ink deep into the skin using sharp force.

Immunity starts in the skin

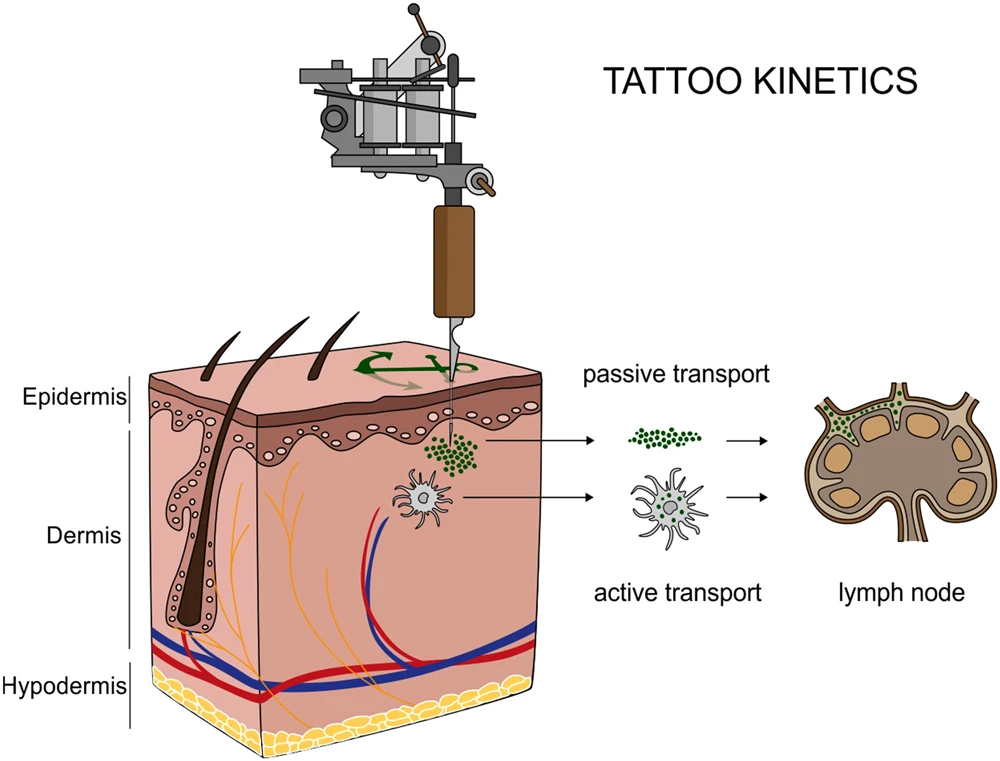

The skin is made up of three major layers; the epidermis, dermis, and a subcutaneous fatty layer, sometimes called the hypodermis (Figure 1 [2]). In this article, we will focus on the epidermis and dermis. The epidermis is the outermost layer of the skin and our first line of defense against bacteria in everyday life. The epidermis contains our melanocytes, the cells that give our skin pigment, and is constantly refreshing itself with new skin cells – keratinocytes – as we shed old ones [2]. This layer is also the locale of immune cells called Langerhans cells. When invading pathogens breach the epidermis, these cells engulf the threat and present specific antigens, which are essentially threat-specific flags, to another immune cell population called T cells [3]. T cells consist of many subtypes, but their overall function is to detect the antigens presented by other immune cells, attach to them, and kill the infection [4].

Dermis design

During the process of tattooing, an artist uses a sharp needle-like tool to puncture the skin repeatedly, delivering ink to the dermis. The dermis is the largest layer of the skin, constituting 90% of its thickness [2]. The tattoo needle is coated in the desired ink, and in most cases, is part of a mechanical tattoo gun that pulses the needle very quickly at set speeds into the skin. Each time the needle pulses, it passes through the epidermis and deposits ink into the dermis. The ink reaches the upper layer of the dermis, where it pools [5]. Not all ink is absorbed during the tattooing process, which is why the artist may have to wipe the area clean while they are working – and why tattoos tend to ‘leak’ during the immediate healing process. However, it is not only ink which may leak, but also lymph fluid and some blood [6]. A tattoo is essentially a new wound – this fluid is part of our immune response. Thousands of punctures to the skin alert our immune cells to flock to the worksite to begin healing our tissue almost immediately. Lymphatic vessels, part of our bodies’ lymphatic system, are another player in this reaction. They collect small excess particles of ink and passively transport it away from the tattoo site, towards nearby lymph nodes, where it is broken down by the body (Figure 2 [7]). Interestingly, recent work has found that some of this ink may remain in the lymph nodes for many years after the initial immune response, a finding that was observed in both donor humans and mouse models [7]. As aforementioned, free lymph fluid also speeds this process up by leaking out excessive ink rather than bringing it further into the dermis.

In addition to the lymphatic response, the immune system has another component that is crucial in the formation and maintenance of tattoos: macrophages. These immune cells are aptly named for their function – their names translate from the Greek macro – big, and phage – eater [6]. Picture Kirby swallowing up an enemy (or a tasty treat), or Pac-Man gobbling up dots (gif). Macrophages are large immune cells which phagocytose, or “eat,” debris. When ink is injected into the dermis, local macrophages ingest it and remain visible beneath the epidermis. Macrophages typically break down small intruding substances such as bacteria or other foreign particulates, but interestingly, they do not break down tattoo ink droplets, which are too large to metabolize [8,9]. This fact is key to the maintenance of a visible tattoo. Since the ink remains inside the macrophage, specifically located in the skin cells which have been injected with ink, visible art remains in the dermis [8].

An inky situation

While we now know the importance of macrophages in tattooing, it was not always so clear. For a long time, people were unsure exactly how ink was processed by the skin during a tattoo. Despite determining that dermal (skin) macrophages are involved, there is still much to uncover about the maintenance and turnover of ink-laden macrophages. Additionally, we do not yet understand how other cells in the skin are involved in tattoo maintenance. Our understanding of how skin processes tattoo ink was strengthened by quantitative research, some of which was performed in laboratory mice. Yes, mice with tattoos!

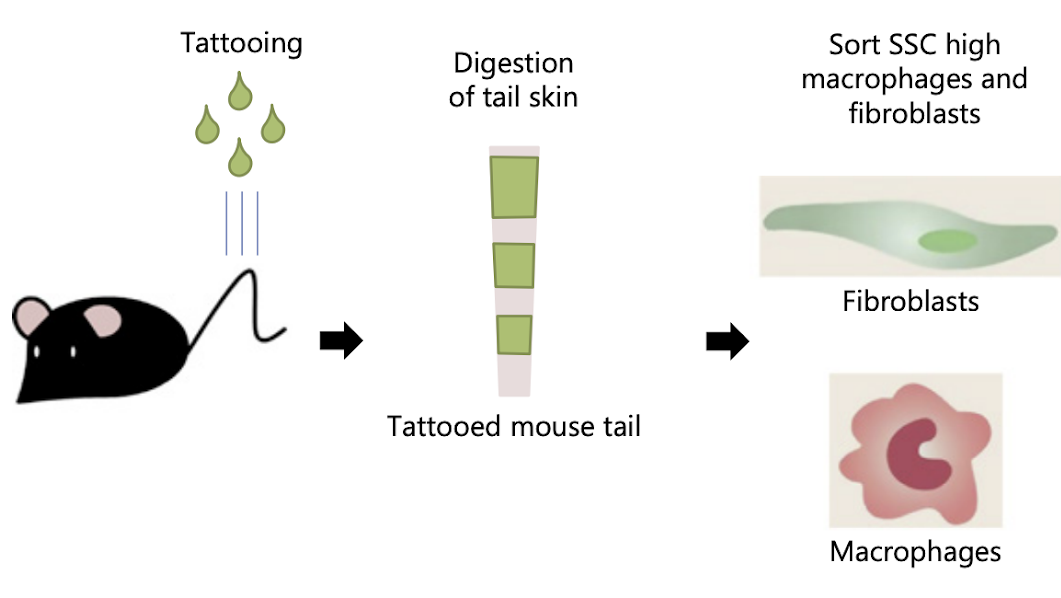

In one study, mice were tattooed uniformly on their tails with green ink. After a period of healing, the tattooed skin was analyzed, specifically assessing present macrophages and another type of skin cell called fibroblasts, which are a part of connective tissue and not involved in the immune response (Figure 3 [8]). Although fibroblasts are not immune cells, they are important for scar formation and healing due to their role in constructing and deconstructing collagen structures that strengthen the dermis. This study utilized a tool which inactivated macrophages in tattooed skin during the healing period. The goal of this depletion experiment was to assess the effect of losing most macrophages’ ability to engulf ink. Would the tattoo fade, or would other cells step in to hold onto the ink? This study found that in skin samples where macrophage activity was depleted, a slightly higher percentage of fibroblasts contained tattoo ink (Figure 4 [8]). So, although fibroblasts did not completely step in to fill the shoes of the macrophages, they did in fact appear to be part of a compensatory response which resulted in the tattoo remaining intact. This study opens up interesting directions for future study to further elaborate on other skin cells which might help cling to ink when macrophages let it go.

Aftercare

Considering that macrophage depletion did not cause tattoos to disappear, it is safe to say that macrophages are not the only types of cells involved in tattoo maintenance, but their role is not to be disparaged. In fact, macrophages are thought to be part of why tattoo removal is so difficult. Although macrophages do eventually die, they have relatively long lifespans, living anywhere from several months to several years [10]. When they die and release their inky contents, new macrophages are always ready and able to eat up the ink expelled by their dying comrades. Alas, some ink may be lost during each transfer, and some believe this may contribute to why inky art tends to fade over time – eventually, ink particles may become small enough for a macrophage to break down, no longer simply holding onto it [9]. Even so, do not fret – your ink can be clean and crisp for a very long time, thanks to the work of your skin cells.

Citations

[1] Tāmoko: Traditional Māori Tattoo: 100% pure New Zealand. 100% Pure New Zealand. (n.d.). https://www.newzealand.com/us/feature/ta-moko-maori-tattoo/

[2] Cleveland Clinic. (2021, October 13). Skin: Layers, structure and function. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/10978-skin

[3] Monnot, G. C., Wegrecki, M., Cheng, T.-Y., Chen, Y.-L., Sallee, B. N., Chakravarthy, R., Karantza, I. M., Tin, S. Y., Khaleel, A. E., Monga, I., Uwakwe, L. N., Tillman, A., Cheng, B., Youssef, S., Ng, S. W., Shahine, A., Garcia-Vilas, J. A., Uhlemann, A.-C., Bordone, L. A., … de Jong, A. (2022). Staphylococcal phosphatidylglycerol antigens activate human T cells via cd1a. Nature Immunology, 24(1), 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-022-01375-z

[4] Cleveland Clinic . (2024, September 10). T cells: Types and function. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/24630-t-cells

[5] Grant, C. A., Twigg, P. C., Baker, R., & Tobin, D. J. (2015). Tattoo ink nanoparticles in skin tissue and fibroblasts. Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology, 6, 1183–1191. https://doi.org/10.3762/bjnano.6.120

[6] Wilhelm, M. (2018, March 8). Tattoo you: Immune system cells help keep ink in its place. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/03/08/591315450/tattoo-you-immune-system-cells-help-keep-ink-in-its-place

[7] Schreiver, I., Hesse, B., Seim, C., Castillo-Michel, H., Villanova, J., Laux, P., Dreiack, N., Penning, R., Tucoulou, R., Cotte, M., & Luch, A. (2017). Synchrotron-based ν-XRF mapping and μ-ftir microscopy enable to look into the fate and effects of tattoo pigments in human skin. Scientific Reports, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11721-z

[8] Strandt, H., Voluzan, O., Niedermair, T., Ritter, U., Thalhamer, J., Malissen, B., Stoecklinger, A., & Henri, S. (2020). Macrophages and fibroblasts differentially contribute to tattoo stability. Dermatology, 237(2), 296–302. https://doi.org/10.1159/000506540

[9] Amgen Foundation. (2022, April 12). Tattoos and the immune system: More than skin deep. Tattoos and the Immune System: More Than Skin Deep | Amgen Biotech Experience. https://www.amgenbiotechexperience.com/tattoos-and-immune-system-more-skin-deep %5B10%5D Parihar, A., Eubank, T. D., & Doseff, A. I. (2010). Monocytes and macrophages regulate immunity through dynamic networks of survival and cell death. Journal of Innate Immunity, 2(3), 204–215. https://doi.org/10.1159/000296507

You must be logged in to post a comment.