Tags

Learning and Concussions: a Brain Renovation

What a Wonderful World

Being human, with the brains we have, is wonderful. Our brains give us an amazing ability to learn that sets us apart from other animals. We aren’t the fastest, strongest, or biggest. But we sit at the top of the food chain, enjoying a wonderful world, because of our ability to learn. Without it, we wouldn’t have neuroscience, phones, airplanes, movies, skyscrapers, tasty recipes, highways, hot tubs, or any of the man-made things we learned to create that define our experiences. My ability to learn has always been one of my favorite things about life and about myself. I love learning. I enjoy everything about it. Doing it. Understanding better ways to do it. Watching others do it. And being in environments that promote it. I think Louis Armstrong’s “What a Wonderful World” beautifully captures this sentiment of loving learning, “I hear babies cry \ I watch them grow \ They’ll learn much more \ Than I’ll ever know \ And I think to myself \ What a wonderful world” (Genius).

As is often the case, I took my ability to learn for granted until it was impaired by my first concussion. Feeling drowsy, foggy-headed, and inattentive reminded me how much I love learning. I wrote this article to remind people of our special capability to learn and how it can be altered in the blink of an eye. In detailing what we know is going on in the brain during a concussion, I will focus on the impact–pun intended–a concussion has on synaptic plasticity, the proposed molecular correlate of learning, as well as on cognitive outcomes. I will use the following analogy: a concussion is an unwanted, semi-planned house renovation, where your brain is the house. I recognize that this analogy has its limitations, but I think it will help readers learn the important aspects of the detailed mechanisms that dictate the outcome of a concussion.

Demolition – the impact

In this hypothetical, unwanted—key word—house renovation, a demolition team abruptly shows up, sets C4 explosives in your living room, and blows them up. This is the impact to your head that causes the concussion. And just as a C4 explosion would clear out the center of the living room by scattering furniture into clusters of debris, burst pipes, and damage walls in an uncontrolled, chaotic manner, focal head trauma jostles and, consequently, damages neurons at the site of impact and causes blood vessels to rupture or become permeable. Upon impact, the force applied to your head is transferred to neurons’ cytoskeletal components, mainly microtubules—the support beams inside a wall in this analogy. These strong scaffolds that line your axons break apart, causing structural instability and, more importantly to synaptic health, swelling along the axons. Microtubules are multifunctional support beams that also facilitate the transport of proteins and molecules along the axon. When microtubule structure is disrupted from the C4 explosion, transport is disrupted, or even halted, as well. This lack of intracellular transport is detrimental to synaptic plasticity and synapses, in general, as receptors, channels, anchoring proteins, and signal transducers that localize to the synapse cannot perform their function if they don’t make it to there (Chen et al., 2009; Jamjoom et al., 2020). Thus, think of this axonal swelling as your clusters of debris in the living room.

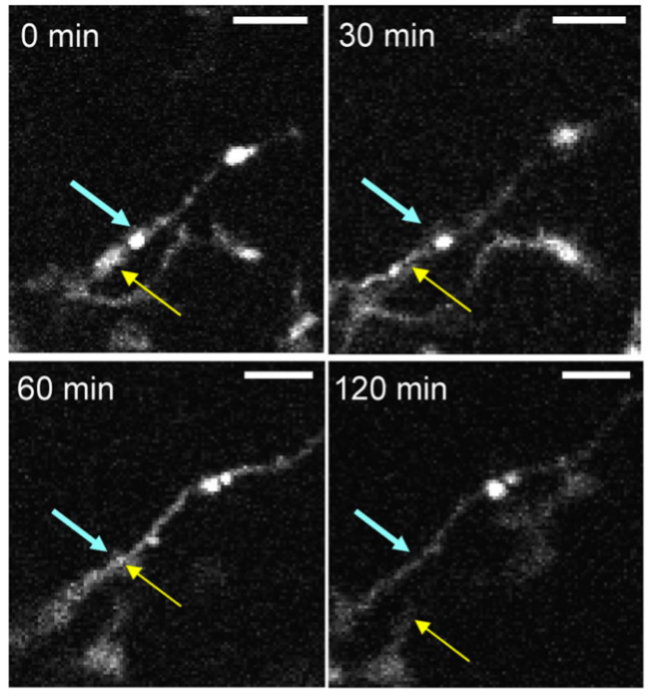

The bursting pipes and resultant flooding in our renovation analogy can manifest in two main phenomena during a concussion. The first, and most obvious, is leaking blood vessels—the pipes. The mechanical force of the head impact can disrupt contacts between cells that maintain the ultratight blood-brain-barrier that strictly regulates the flow of nutrients between the brain and blood in a healthy individual. The second is the damaged neurons and glial cells that “flood” the extracellular space with intracellular components such as nucleic acids, heat shock proteins, and other molecules that signal to surrounding cells that they are in trouble. These two pipe bursts result in a recruitment of peripheral immune cells into the brain and an activation of resident immune cells. These immune cells constitute our hands-on demolition team who sledgehammers remaining structures, cleans up trash, and calls for more backup if needed. These cells include neutrophils, macrophages, T and B cells, microglia, and astrocytes, along with many others (Jamjoom et al., 2020; Jarrahi et al., 2020). Neutrophils, macrophages, and microglia are the garbage men, mainly phagocytosing cellular debris. However, specific immune signals also cause microglia to phagocytose synapses (Wake et al., 2009). T cells mainly kill invading pathogens and dying neuronal, glial, and endothelial cells—they are our sledgehammer-wielding guys. All of these immune cells together act as recruiters, secreting cytokines and chemokines that signal the need for backup to other immune cells (Jarrahi et al., 2020). In relation to synapses and plasticity, one of the secreted cytokines, TNFa, induces overexpression of calcium-permeable receptors that add to the excitotoxicity discussed below and kills synapses (Stellwagen et al., 2005).

The impact of a concussion causes another type of pipe burst regarding neurons. In addition to the neuron flooding the extracellular space, mechano-sensitive sodium channels open, allowing a massive influx of sodium into the neuron. The resulting depolarization initiates two detrimental cascades: 1) voltage-gated calcium channels open, allowing massive influxes of calcium into that neuron and 2) excitatory neurons release glutamate, depolarizing their neighboring neurons and starting an unexpected, excessive wave of activity called excitotoxicity (Jarrahi et al., 2020; Romeu-Mejia et al., 2019; Wolf et al., 2001). In our analogy, excitotoxicity is like the living room’s electrical circuit being short-circuited; it’s supercharged in the short-term, but if left like that for too long, it damages the circuit’s components and eventually shuts the circuit down. One way excitotoxicity can damage the brain’s circuits is the massive influx of calcium into neurons. Calcium activates a number of enzymes that have detrimental effects when they are not tightly regulated. One example is nitric oxide synthase (NOS), which produces reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS have an unpaired electron, so they zip around stealing electrons from important proteins and lipids, changing the shape and, therefore, function of these macromolecules and making them dysfunctional (Jamjoom et al., 2020). ROS are like neighborhood hooligans that explore and vandalize vacant, renovated houses. Calcium also overloads mitochondria, making them dysfunctional, furthering the energy crisis in which a post-concussion neuron already exists (Szydlowska & Tymianski, 2010).

To refocus on synapses and plasticity, all of these early events of a concussion either drive the cell into a state where it cannot support the maintenance of synapses, ultimately causing synaptic dysfunction, or the synapse is directly removed, as in the case of microglial phagocytosis. In fact, these aforementioned mechanisms are believed to be the cause of the 40-70% reduction in synapses at the site of injury seen in the first 7 days after a concussion (Jamjoom et al., 2020). The remaining synapses, especially in the hippocampus, often show reduced LTP and enhanced LTD for 30 days, and sometimes longer, after an injury in animals and humans (De Beaumont et al., 2012; Eyolfson et al., 2024). So, this house renovation is pretty bad so far, huh? The good news is that our brains are very plastic even as adults, so the rest of the renovation should be promising.

Renovation – tissue replacement

After about 7-10 days of inflammation, oxidative stress, and excitotoxicity—sledgehammers, hooligans, flooding, and short-circuiting—the injury caused by the concussion is contained and under control, and it is time for our architects, interior designers, and carpenters to step in. As for these labels, they are oversimplified but make it easier to understand how this minor brain injury is cleaned up. Our architects are astrocytes, which elongate and form a border around damaged tissue to protect the uninjured neurons from inflammation and oxidative stress (Burda & Sofroniew, 2014). Emerging evidence suggests that astrocytes can coordinate the repair response by recruiting other cell types into the injury site and preventing other cell types from exiting (Burda & Sofroniew, 2014; Shen et al., 2024). Endothelial progenitors act as plumbers by proliferating and eventually differentiating into endothelial cells that make up the new blood vessels. They will supply water to the renovated room. Cells from a fibroblast lineage act as carpenters that produce connective tissue to provide structure and hold everything in place. These connective tissues are the support beams in our new room’s walls. Another specialty carpenter are neuronal progenitors that occupy the area outside of the astrocytic border (Burda & Sofroniew, 2014). Now, with the right materials in place, it is time to remodel the new room in our house. I will focus on the role of these specialized carpenters—neuronal progenitors—and how they may play a crucial role in synaptic plasticity and regaining cognitive function after a concussion.

Remodeling – synaptic plasticity and circuit rewiring

I want to emphasize that while remodeling in a home renovation may occur after building new structures, the human brain does not operate in this step-by-step process. Instead, renovation and remodeling occur somewhat simultaneously. Thus, starting at 7 days post-injury, the number and health of dendritic spines and synapses increases in humans and animals (Nahmani & Turrigiano, 2014). While the exact mechanisms of this resurgence in synapses is not completely understood, we have some hints. The first contributors are our lovely neuronal progenitor carpenters. In particular, neurogenesis, the birth of new neurons, has been observed in two locations after a concussion: the hippocampus, an area of the brain crucial for learning and memory, and the injured cortical area (Sun et al., 2007; Zheng et al., 2013). In fact, several groups have shown in animal models that these progenitors multiply, mature, and then mingle with existing neurons so that they integrate into the circuitry (Hastings & Gould, 1999; Sun et al., 2007). So, maybe these neural progenitors are less specialized than we think, acting as carpenters and electricians. These new neurons are one source of additional synapses seen in the plasticity phase of recovery from a concussion.

Another potential source is the growth of new synapses from existing neurons. Extending out from the injured area, astrocytes become less and less “reactive,” meaning they are less concerned with injury clean up and more concerned with their normal duties such as helping neurons be healthy neurons. One of the ways they do this is through gliotransmission, which is when the astrocytes that live at the synapse secrete molecules that aid in synaptic firing. One of these molecules, D-serine, binds to one of the main receptors for excitatory neurotransmission. In other words, D-serine from astrocytes can induce the strengthening of a synapse by helping the neurons it neighbors to fire together and, therefore, wire together. After a concussion, increases in D-serine levels have been observed in the perilesion area (Burda & Sofroniew, 2014; Halassa & Haydon, 2010). Thus, the coordinated activity of astrocytes, existing neurons, and new neurons can rewire the brain’s circuitry and increase the number of synapses—plasticity!

More neurons and synapses do not necessarily mean improved cognitive functioning, or improved learning ability. These synapses need to do something, help the organism solve problems, learn. Evidence suggests that these neurons do do that. The timing of these carpenters/electricians performing their duty aligns with the functional improvement in memory-related tasks in rodents (Sun et al., 2007). Depleting the neuronal progenitors before they ever become neurons also reduces the functional recovery seen in wildtype animals (Jin et al., 2010). This is causal evidence that neurogenesis and circuit rewiring contribute to rodents’ recovery of learning and memory capabilities. These studies are ethically and technically impossible to do in humans, but one could imagine that this is also the case in humans, as post-mortem tissue shows that neurogenesis and synaptic formation occurs after a concussion in humans, too. Furthermore, when humans experiencing cognitive decline after a concussion deliberately train their brain in tasks of speed and accuracy of processing, they improve dramatically compared to active controls (Mahncke et al., 2021). Again, it is impossible to directly attribute this recovery to synaptic plasticity, but it almost has to be the case that synaptic plasticity is at work for these people to improve their ability to learn.

A New Home

While the renovation certainly was not wanted, and finding the positives in enduring a concussion is hard to do, I hope after reading this article that you’ve realized how incredible our brains are. Before a concussion, we have this amazing ability to learn. After a concussion, we may have lost some cognitive function for the time being, but we still maintain this incredible plasticity, meaning we can get back and even exceed the cognitive level we held prior to the injury. It is critical to highlight that this article is about concussions, mild traumatic brain injuries. The severity of the injury, along with other factors such as age and the number of injuries, influence the amount of injury to our brains and, consequently, the cognitive level to which that plasticity will allow us to climb after the injury. With that being said, if you’ve suffered a mild traumatic brain injury and are nervous about your brain’s long-term wellbeing as I was, don’t be scared. Do yourself a favor and train your brain. Play a part in the renovation so that your new home is one that allows you to enjoy this “Wonderful World.”

References

Burda, J. E., & Sofroniew, M. V. (2014). Reactive Gliosis and the Multicellular Response to CNS Damage and Disease. Neuron, 81(2), 229–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.034

Chen, X.-H., Johnson, V. E., Uryu, K., Trojanowski, J. Q., & Smith, D. H. (2009). A Lack of Amyloid β Plaques Despite Persistent Accumulation of Amyloid β in Axons of Long-Term Survivors of Traumatic Brain Injury. Brain Pathology, 19(2), 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00176.x

De Beaumont, L., Tremblay, S., Poirier, J., Lassonde, M., & Théoret, H. (2012). Altered Bidirectional Plasticity and Reduced Implicit Motor Learning in Concussed Athletes. Cerebral Cortex, 22(1), 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhr096

Eyolfson, E., Suesser, K. R. B., Henry, H., Bonilla-Del Río, I., Grandes, P., Mychasiuk, R., & Christie, B. R. (2024). The effect of traumatic brain injury on learning and memory: A synaptic focus. The Neuroscientist, 10738584241275583. https://doi.org/10.1177/10738584241275583

Halassa, M. M., & Haydon, P. G. (2010). Integrated Brain Circuits: Astrocytic Networks Modulate Neuronal Activity and Behavior. Annual Review of Physiology, 72(Volume 72, 2010), 335–355. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135843

Hastings, N. B., & Gould, E. (1999). Rapid extension of axons into the CA3 region by adult-generated granule cells. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 413(1), 146–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19991011)413:1<146::AID-CNE10>3.0.CO;2-B

Jamjoom, A. A. B., Rhodes, J., Andrews, P. J. D., & Grant, S. G. N. (2020). The synapse in traumatic brain injury. Brain, 144(1), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaa321

Jarrahi, A., Braun, M., Ahluwalia, M., Gupta, R. V., Wilson, M., Munie, S., Ahluwalia, P., Vender, J. R., Vale, F. L., Dhandapani, K. M., & Vaibhav, K. (2020). Revisiting Traumatic Brain Injury: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Interventions. Biomedicines, 8(10), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines8100389

Jin, K., Wang, X., Xie, L., Mao, X. O., & Greenberg, D. A. (2010). Transgenic ablation of doublecortin-expressing cells suppresses adult neurogenesis and worsens stroke outcome in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(17), 7993–7998. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1000154107

Mahncke, H. W., DeGutis, J., Levin, H., Newsome, M. R., Bell, M. D., Grills, C., French, L. M., Sullivan, K. W., Kim, S.-J., Rose, A., Stasio, C., & Merzenich, M. M. (2021). A randomized clinical trial of plasticity-based cognitive training in mild traumatic brain injury. Brain, 144(7), 1994–2008. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awab202

Nahmani, M., & Turrigiano, G. G. (2014). Adult cortical plasticity following injury: Recapitulation of critical period mechanisms? Neuroscience, 0, 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.04.029

Romeu-Mejia, R., Giza, C. C., & Goldman, J. T. (2019). Concussion Pathophysiology and Injury Biomechanics. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 12(2), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-019-09536-8

Shen, Z., Feng, B., Lim, W. L., Woo, T., Liu, Y., Vicenzi, S., Wang, J., Kwon, B. K., & Zou, Y. (2024). Astrocytic Ryk signaling coordinates scarring and wound healing after spinal cord injury (p. 2024.10.16.618727). bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.10.16.618727

Stellwagen, D., Beattie, E. C., Seo, J. Y., & Malenka, R. C. (2005). Differential Regulation of AMPA Receptor and GABA Receptor Trafficking by Tumor Necrosis Factor-α. Journal of Neuroscience, 25(12), 3219–3228. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4486-04.2005

Sun, D., McGinn, M. J., Zhou, Z., Harvey, H. B., Bullock, M. R., & Colello, R. J. (2007). Anatomical integration of newly generated dentate granule neurons following traumatic brain injury in adult rats and its association to cognitive recovery. Experimental Neurology, 204(1), 264–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.11.005

Szydlowska, K., & Tymianski, M. (2010). Calcium, ischemia and excitotoxicity. Cell Calcium, 47(2), 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceca.2010.01.003

Wake, H., Moorhouse, A. J., Jinno, S., Kohsaka, S., & Nabekura, J. (2009). Resting Microglia Directly Monitor the Functional State of Synapses In Vivo and Determine the Fate of Ischemic Terminals. Journal of Neuroscience, 29(13), 3974–3980. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4363-08.2009

Wolf, J. A., Stys, P. K., Lusardi, T., Meaney, D., & Smith, D. H. (2001). Traumatic Axonal Injury Induces Calcium Influx Modulated by Tetrodotoxin-Sensitive Sodium Channels. Journal of Neuroscience, 21(6), 1923–1930. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01923.2001

Zheng, W., ZhuGe, Q., Zhong, M., Chen, G., Shao, B., Wang, H., Mao, X., Xie, L., & Jin, K. (2013). Neurogenesis in Adult Human Brain after Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, 30(22), 1872–1880. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2010.1579

You must be logged in to post a comment.