April

24

April

24

Tags

This brainless blob might outsmart you

In the spring of 2017, Hampshire College welcomed a new faculty member, one without a brain or even a nervous system. Physarum polycephalum, a species of slime mold, joined the campus not just as a scientific curiosity but as a non-human thinker. As the college put it, this organism “researches important problems from a non-human perspective and enhances intellectual life on campus by helping students and colleagues think about the world without human biases.” Psysarum Mold has an office that students can come visit in their science center.

Slime molds (from phylum Myxomycetes) are single-celled organisms with no neurons, no synapses, and no centralized control. Yet, their behavior is anything but simple. From solving mazes to optimizing complex networks, these blobs routinely perform feats that challenge our assumptions about how intelligence emerges. The more we learn from them in the lab, the more we’re confronted with deeper philosophical questions about what it means to be conscious.

What are slime molds?

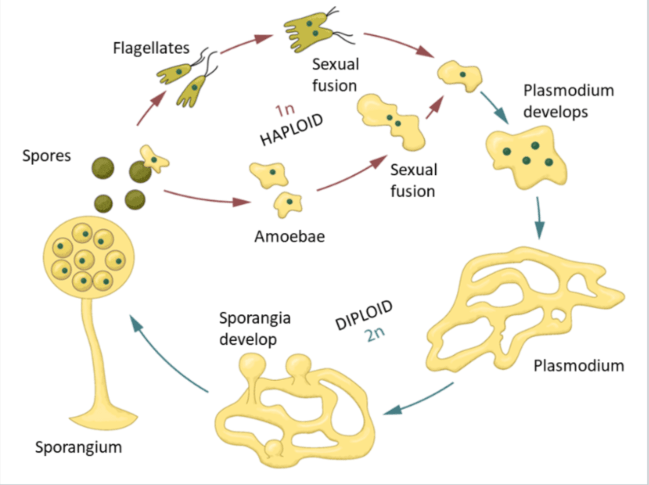

Slime molds have long puzzled biologists. During one phase of their life cycle, they form spore-producing structures that look slimy and mushroom-like (Fig. 1), which led scientists to once classify them as fungi [1]. However, slime molds aren’t fungi, plants, or animals. They belong to an entirely different group of organisms: the protists.

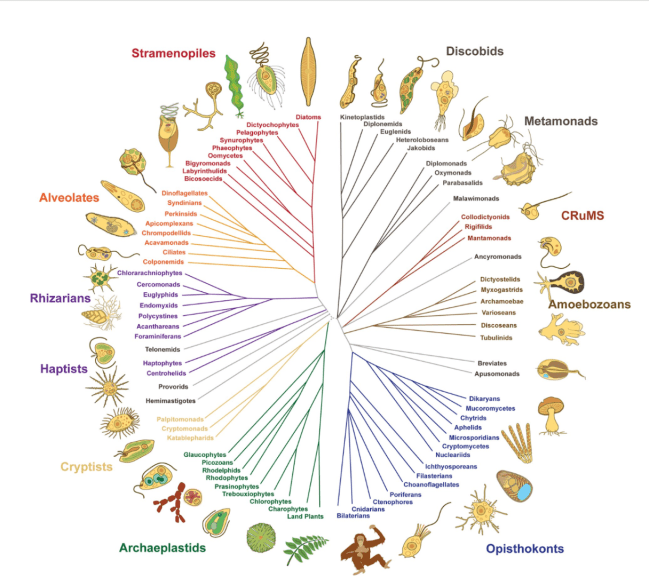

Protists are a diverse, catch-all category for eukaryotic organisms that don’t fit neatly into the other kingdoms (Fig 3). That means they have complex cells with nuclei, like animals and plants, but they don’t follow the typical rules of those groups. In fact, most life on Earth is neither plant, animal, nor fungus but something else entirely, often lumped into this “protist” bucket. Protists include things as different as slime molds, algae, and the single-celled predators that swim through pond water. Our familiar categories of plants, animals, and fungi actually only capture a very narrow slice of Earth’s biodiversity.

Slime molds are especially ancient members of this group. Fossil evidence suggests they’ve barely changed in hundreds of millions of years [3]. You might say these veterans of Earth might have already reached peak performance and no longer need to keep evolving. They also play a vital role in ecosystems, breaking down decaying matter and cycling nutrients, helping to maintain the balance of life in forests, soils, and wetlands.

There is a lot of diversity of being within slime molds. Some live out their lives as solitary cells, others form colonies, and some shift between solitude and cooperation, coming together with fellow molds when it’s time to forage or reproduce. Slime molds offer a striking example of collective intelligence both in solitude and in their cooperative phase. Without a brain or nervous system, they still manage to coordinate movement, solve problems, and make decisions as a group. These organisms make us rethink what it means to be conscious and where intelligence emerges.

Smart without a spine

Slime molds do not have a brain or a nervous system. However, studies in the lab have shown that they can exhibit complex behavior that suggests hallmarks of intelligence. Classically, slime molds have been shown to efficiently explore mazes to find food in the form of oats. Instead of blindly spreading out in search of their food reward, over a couple hours, the slime mold connected two food sources at different ends of a U-shaped maze via the shortest possible route and retracted the branches of their body from the dead ends of the maze. retracted branches from dead ends [4]. This shows that slime molds are able to solve hard problems and maximize resources.. In a more useful demonstration of ability, researchers constructed the layout of food to match the map of cities surrounding Tokyo, for which the slime mold recreated a strikingly similar network to the actual railway system [5]. The network they created was efficient, redundant, and optimized for traffic flow, all being solutions we typically associate with intelligent design. Despite not having a brain, nor a degree in city planning, the slime mold was able to recreate in a day something that took a team of engineers months.

Slime molds also exhibit signs of memory and decision-making. In studies where environmental conditions were varied in regular intervals, the slime mold began to anticipate when the next change would occur, pausing its movement in sync with the rhythm. Other experiments haveshown that Physarum can “learn” to avoid unpleasant stimuli. When faced with uncertain conditions, it makes trade-offs that balance risk and reward, reallocating its growth depending on available nutrients or stressors [7]. Sensing, adapting, and deciding are all hallmarks of intelligence. Maybe intelligence is not a property of brains alone, but rather an adaptive behavior in context.

No nervous system, no problem

While we still have much to understand about how slime molds are able to reach such intelligent solutions, we do know a little about how they work. Slime molds are able to coordinate movement and information flow across the cell through something called cytoplasmic streaming, which is a rhythmic pulsing of their inner fluid. Because there is no central command station, their behavior emerges from a distributed, decentralized process where they rely on chemical signaling and spatial feedback. They are able to leverage these tools to reinforce successful paths by flowing more strongly towards the nutrient-rich areas and retracting from those that are less promising.

Wrestling with what it means to have a mind

Exploring all that slime molds are capable of forces us to reconcile with what a mind is. Is having a mind substrate-dependent–is a brain and nervous system required, or is the mind an emergent phenomenon from some other end? What defines intelligence, and can intelligence arise from the interaction of some body and the environment alone? The brain is one solution in biology to interact with the environment, but cognition may not require representation or self-awareness like we traditionally may think it does. Learning more about what the boundaries are of non-human intelligence begs the question of whether something could be intelligent without subjective experience. Understanding the way a single-celled organism can do things that we traditionally think requires a brain will help us disrupt the traditional hierarchies of intelligence, where we place human intelligence at the top and all other living things below us. In reality, human intelligence is special and unique in its own way, but many other organisms, animals or not, are able to thrive and succeed in ways we still do not have the tools to understand. How are we to say we are the smartest living things when we still do not even have the correct tools or vocabulary to measure other organisms? Slime molds open the door to non-neural, embodied, decentralized models of cognition. If a blob of slime can think, maybe the mind is not where we thought it was.

References:

[1] Stephenson, Steven L. “The Myxomycetes: Nature’s Quick-Change Artists.” American Scientist, Sigma Xi, https://www.americanscientist.org/article/the-myxomycetes-nature%E2%80%99s-quick-change-artists. Accessed 24 Apr. 2025.

[2] Keeling, Patrick J., and Yana Eglit. “Openly Available Illustrations as Tools to Describe Eukaryotic Microbial Diversity.” PLOS Biology, vol. 21, no. 11, 21 Nov. 2023, e3002395. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002395.

[3] Kooser, Amanda. “Scientists Find Astounding Slime Mold Trapped in Amber for 100 Million Years.” CNET, 13 Nov. 2019, https://www.cnet.com/science/scientists-find-astounding-slime-mold-trapped-in-amber-for-100-million-years/.

[4] Tero, Atsushi, et al. “Rules for Biologically Inspired Adaptive Network Design.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 107, no. 17, 2010, pp. 7635–7639. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0911742107.

[5] Dussutour, Audrey, and David Latty. “Amoeboid Organisms Use Extracellular Secretions to Make Rational Decisions.” Behavioral Processes, vol. 88, no. 1, 2011, pp. 84–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2011.08.003.

[6] McRae, Mike. “Slime Mould Builds a Replica of Tokyo’s Rail Network.” National Geographic, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/slime-mould-attacks-simulates-tokyo-rail-network. Accessed 24 Apr. 2025.

[7] Reid, Chris R., et al. “Slime Mold Uses an Externalized Spatial ‘Memory’ to Navigate in Complex Environments.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 109, no. 43, 2012, pp. 17490–17494. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1215037109.

[8] Brain, Marshall. “10 Fascinating Facts About Slime Mold.” HowStuffWorks, https://science.howstuffworks.com/life/biology-fields/slime-mold-facts.htm. Accessed 24 Apr. 2025.

You must be logged in to post a comment.