October

02

October

02

Tags

Bioluminescence: You Glow Girl

If you’re local to Southern California, you’ve probably heard that there is a brief night or two every now and then when the ocean waves crashing on the sand seem to have a bright blue glow. If you haven’t seen this amazing phenomenon, maybe you’ve happened upon a glowing jellyfish at your local aquarium or a flickering firefly on a summer night. These are just a few examples of the natural glow we call “bioluminescence,” or the phenomenon during which living organisms produce light through a chemical reaction [1]. But how does this occur, and why? In this article, we will explore the science of bioluminescence, as well as how and why it works in different species and in the ocean’s waves.

LET’S GET CHEMICAL

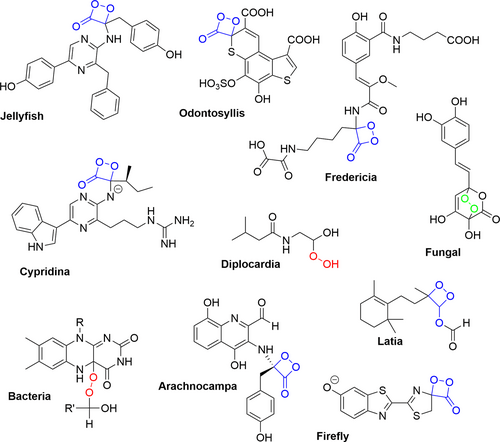

The chemical reaction that creates the emitted light we see begins with a compound called luciferin. Luciferin can vary in molecular structure across different species, however it still works in more or less the same manner (Figure 1). Luciferin reacts with oxygen, with the help of an enzyme called luciferase, to create an unstable high energy intermediate. This high energy intermediate is a type of peroxide, meaning it has a weak single bond between two oxygen atoms (represented by the pink line in Figure 2. see also the blue “O – O” sections in Figure 1). Peroxides are notoriously unstable, and thus high energy, due to this weak bond. When the bond breaks, oxyluciferin (which is just oxygen and luciferin) is released in an excited state with lots of energy. This energy is released in a burst of light as oxyluciferin returns to its natural resting state [1].

YOU GOTTA GLOW YOUR OWN WAY

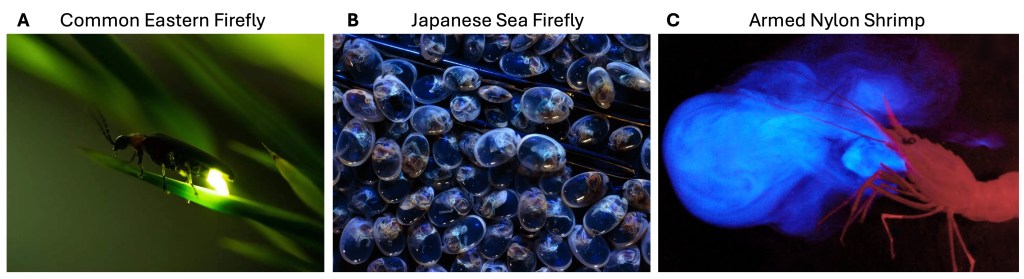

Bioluminescent species are not always glowing, even though they always have luciferin. Since the light-producing reaction requires both luciferin and oxygen, bioluminescence can be turned on or off by introducing these molecules to one another or keeping them apart, respectively. Many bioluminescent animals have luciferin stored in specific light organs that regulate the amount of oxygen being let in. This way, the animal is able to control when they light up. For example, the common firefly (Photinus pyralis, Figure 3a) typically produces light in flashes, often seen as a sort of flickering, which is linked to mating behaviors (or flickering firefly flirting, if you will) [2]. Other species, such as the Japanese Sea Firefly (Cypridina Hilgendorfii, Figure 3b) have a light organ that produces and secretes luciferin as well as a separate light reflection organ dedicated to light emission. In these species, bioluminescence is controlled by selective secretion of luciferin into the light reflection organ, which already contains oxygen [3]. Luciferin can also be secreted into the open water, such as is the case for the Armed Nylon Shrimp (Heterocarpus ensifer, Figure 3c), to react with oxygen in the external environment.

Not only do the species capable of bioluminescence look very different from each other, but the luciferin molecules themselves vary quite a bit between species (Figure 1). Scientists believe that this is due to how the different species evolved to use luciferin [4]. When molecules have a similar overall structure with some minor differences, this typically suggests that they were derived from the same original molecule and each adapted to fit their own circumstances (in the same way that siblings often look similar to each other, as well as to their parents, but with some individual differences). On the other hand, molecules like luciferin that are vastly different across species are thought to have evolved separately and somehow ended up having the same function (in the same way that people can look quite similar even with no family relation whatsoever). The theory that different luciferin molecules evolved independently suggests that bioluminescence is an easy adaptation from an evolutionary standpoint, which is reinforced by the large number of marine species capable of bioluminescence. The reason for the adaptation of bioluminescence is still debated among scientists, however it seems to serve many functions including defense against predators, attracting prey, and inter-species communication (like the flickering firefly flirting; see Figure 4 for some underwater examples) [4].

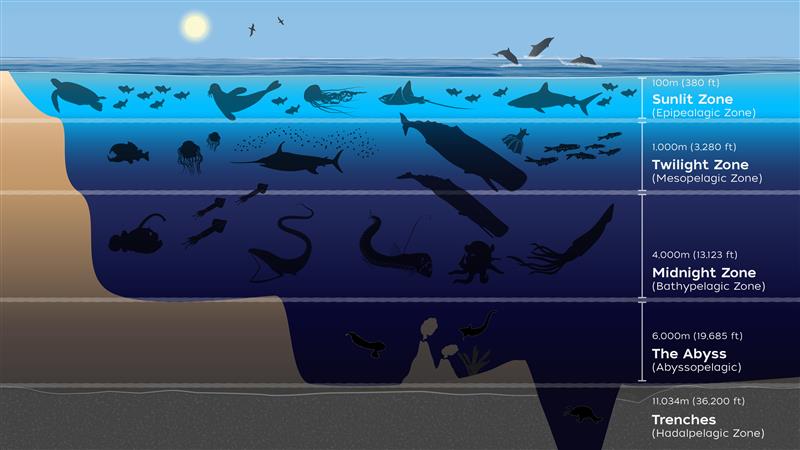

Other than fireflies, the number of bioluminescent species we encounter as land-roaming humans is rather limited. It turns out that most of Earth’s glowing creatures live in the depths of our dark oceans. In fact, scientists estimate that around 76% of marine species have bioluminescent capabilities [5]. The proportion of bioluminescent species relative to non-bioluminescent species also increases the deeper into the ocean you look (Figure 5). Bioluminescence seems to be particularly important for deep ocean species since sunlight can only penetrate the ocean so far. After about 1,000 meters, animals in the ocean live in complete darkness. The only light that occurs past the Twilight Zone (Figure 6) is bioluminescent light, making it critical for most anything that requires vision [5]. In fact, most deep ocean animals have highly precise monochromatic vision with maximal absorbance around 474 – 490 nanometers, meaning they are able to see quite well, but only in shades of blue and green [6]. Most types of bioluminescent light have a wavelength around 470 nanometers, which results in a corresponding green/blue color [4]. So not only are deep sea creatures most likely to be bioluminescent, they are also best suited to see it!

ONE TIDE, TWO TIDES, RED TIDES, BLUE TIDES

Now that we know how different organisms are able to glow, how is it that the tides can? The bioluminescent tides as we see them are actually caused by masses of dinoflagellate plankton (Figure 7), or single-celled microalgae [7] that float near the ocean’s surface and glow when the waves crash. Crashing waves involve a large influx of oxygen into the water, causing a burst of bioluminescent light because oxygen hits the whole group of dinoflagellates on that wave simultaneously. Additionally, the water itself acts as an amplifier by reflecting the light that is emitted. Despite it being too bright out to see this bioluminescence during daytime, the dark red color of large groups of dinoflagellates makes the waves appear red. This is commonly referred to as “red tide,” which is a type of harmful algal bloom where dinoflagellate plankton grow out of control. Among all algal species that produce harmful blooms, ~75% are dinoflagellates [8]. Red tides present a major environmental concern because these masses of algae release toxins and consume large amounts of the oxygen in the water, both of which can be harmful to other marine species. Some of the toxins produced by red tides that are particularly poisonous for marine life include paralytic shellfish toxins, amnesic shellfish toxins, diarrhetic shellfish toxins, neurotoxic shellfish toxins, ciguatera finfish toxins, azaspiracid toxins, and karlotoxins [7]. So, while the bioluminescent waves are quite beautiful to see, they are actually rather harmful to the environment.

ANOTHER KIND OF NATURAL GLOW

Bioluminescence is not the only way that things in nature can glow. While there are a very limited number of species that produce the amazing glow we see in dinoflagellates or fireflies, almost all living organisms actually emit a very small amount of light. Rather than a result of combining luciferin and oxygen, this type of glow is spontaneous and is thought to be a by-product of other chemical reactions. These reactions involve a similar release of light when a peroxide molecule moves from a high energy state (after a broken single oxygen bond) to a resting state [9]. While the process is similar, these reactions do not involve luciferin and are thus not considered bioluminescence. This type of glow is called “ultraweak photon emission,” and can only be detected by specialized cameras with single-photon resolution (approximately 1000 times that of the human eye) [10].

Interestingly, a recent study [10] found that ultraweak proton emission in humans seems to cycle depending on the time of day, with peak photon emission occurring around 4:00PM. The authors expected to see a relationship between light emission and body temperature, however to their surprise there was no connection. Instead, they found that photon emission was inversely correlated with cortisol levels, which are known to vary along with circadian rhythm. As such, the authors speculate that the differences in photon emission seen across a day are driven by changes in energy production related to the circadian rhythm. Further research in this area is needed, however studies of ultraweak photon emission are limited due to the difficulty of collecting data on such a fine resolution.

GLOW ON

Bioluminescence is a rare and beautiful phenomenon that we are still just beginning to understand. There are lots of cool applications of this natural glow, such as linking luciferin to other proteins so we can easily detect them under a microscope. This can even open doors to study other biological processes, such as circadian rhythms [11]. So even if chemistry is not your thing, hopefully this article could shed some light on bioluminescence!

REFERENCES

[1] Schramm S, Weiß D. Bioluminescence – The Vibrant Glow of Nature and its Chemical Mechanisms. Chembiochem. 2024;25(9):e202400106. doi:10.1002/cbic.202400106

[2] Timmins GS, Robb FJ, Wilmot CM, Jackson SK, Swartz HM. Firefly flashing is controlled by gating oxygen to light-emitting cells. J Exp Biol. 2001;204(Pt 16):2795-2801. doi:10.1242/jeb.204.16.2795

[3] Huvard AL. Ultrastructure of the light organ and immunocytochemical localization of luciferase in luminescent marine ostracods (Crustacea: Ostracoda: Cypridinidae). J Morphol. 1993;218(2):181-193. doi:10.1002/jmor.1052180207

[4] Haddock SH, Moline MA, Case JF. Bioluminescence in the sea. Ann Rev Mar Sci. 2010;2:443-493. doi:10.1146/annurev-marine-120308-081028

[5] Martini S, Haddock SH. Quantification of bioluminescence from the surface to the deep sea demonstrates its predominance as an ecological trait. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45750. Published 2017 Apr 4. doi:10.1038/srep45750

[6] Douglas, R.H. and Partridge, J.C. (1997), On the visual pigments of deep-sea fish. Journal of Fish Biology, 50: 68-85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.1997.tb01340.x

[7] Deng, Y., Wang, K., Hu, Z. et al. Toxic and non-toxic dinoflagellates host distinct bacterial communities in their phycospheres. Commun Earth Environ 4, 263 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00925-z

[8] Smayda Theodore J. , (1997), Harmful algal blooms: Their ecophysiology and general relevance to phytoplankton blooms in the sea, Limnology and Oceanography, 42, doi: 10.4319/lo.1997.42.5_part_2.1137.

[9] Cohen S, Popp FA. Biophoton emission of human body. Indian J Exp Biol. 2003;41(5):440-445.

[10] Kobayashi M, Kikuchi D, Okamura H. Imaging of ultraweak spontaneous photon emission from human body displaying diurnal rhythm. PLoS One. 2009;4(7):e6256. Published 2009 Jul 16. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006256

[11] Martin-Burgos B, Wang W, William I, et al. Methods for Detecting PER2:LUCIFERASE Bioluminescence Rhythms in Freely Moving Mice. J Biol Rhythms. 2022;37(1):78-93. doi:10.1177/07487304211062829

Images included in this article:

http://www.mesophotic.org/photos/101

https://www.whoi.edu/ocean-learning-hub/ocean-topics/how-the-ocean-works/ocean-zones/

https://www.britannica.com/science/dinoflagellate

You must be logged in to post a comment.