July

27

July

27

To believe or not to believe: belief effects and the placebo.

A book called ‘The Secret’ caused a real buzz when it was released in 2006. It claimed that you could use the power of your mind to attract and ‘manifest’ all the awesome things you wanted in life. Suddenly, everyone was all about “manifesting their dreams,” as if it were a magical spell. Although most of the ideas in ‘The Secret’ had very little scientific basis, there was something intriguing about the concept that maybe, our mindset could influence our actions and help us achieve our goals.

We’ve all heard those classic lines like, “think positive, and positive things will happen,” or “mind over matter.” They’re often tossed around in a graduation speech or yelled over a microphone at a fitness class. We usually brush them off as clichés, but I wondered if there was some truth to it – if there was, surely there’s a way to use this to our advantage. Imagine if we could Jedi-mind-trick our way into accomplishing whatever we want!

It’s just a placebo…

Probably, the best example of the effect of our thoughts on the physical comes from the field of medicine where the placebo effect has been widely observed. The placebo effect arises as an outcome of the context around medical treatment. While a placebo typically refers to an inert compound/device, usually sugar/glucose, in the form of a pill, it can also occur by just believing one is about to receive treatment, sometimes triggered just by a visit to a medical office or a doctor’s white coat. The placebo was first formally used in the 1950s as a control for pharmaceutical intervention studies (Czerniak and Davidson, 2012). Clinicians observed that patients administered the placebo reported positive health outcomes and a reduction of symptoms, even in the absence of any active drug component (Wager and Atlas, 2015). Since then, the placebo effect has been one of the most robust findings of modern medicine, accounting for ~40% of the symptom relief from prescriptions (Pardo-Cabello et al., 2022). Thus, in clinical trials placebos are often used to demonstrate the efficacy of medical treatment.

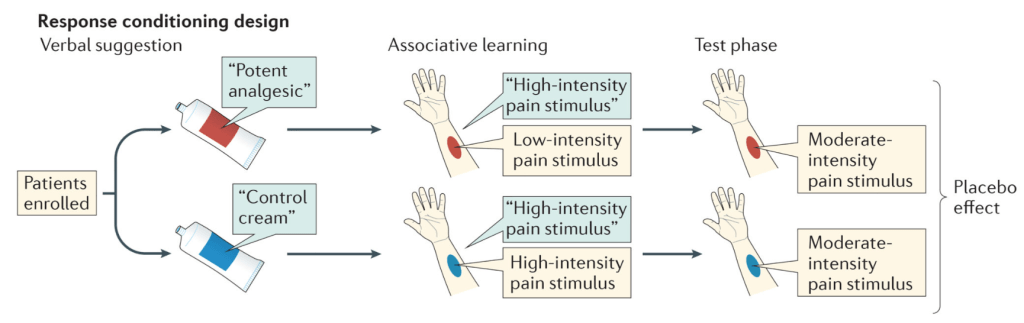

However, there is a downside: just as the placebo effect can drive positive outcomes, its evil twin the nocebo effect can also drive negative health outcomes. The nocebo effect is when patients report side effects or negative responses to treatments, even in the absence of a drug or active ingredient. The nocebo effect is associated with negative expectations from a treatment or can be linked to unintentional negative verbal or non-verbal suggestions from a doctor (Planès et al., 2016). Thus, both the placebo and nocebo effects are highly dependent on an individual’s perception of the environment in which they’re receiving treatment, and importantly, on their personal experience within that setting. Interestingly, these effects are most often observed after a period of “conditioning,” i.e., if the patient has experienced the effect of the real drug beforehand, then in subsequent administrations of the placebo (inert substance), the patient is likely to respond as if they received the drug, indicating that the physical response results in part from mechanisms that arise internally from prior experience. For instance, in a study looking at placebo responses to a painful stimulus (Nakamura et al., 2012), participants were given three identical inert creams that they believed to be of different analgesic (pain-relief) strengths (control, weak, and a strong creams). During the conditioning phase, participants were instructed to use the cream to relieve the pain, while autonomic responses that signal the degree of pain such as pupil diameter, electroencephalography (EEG) and skin conductance were recorded. These measures provided objective biological measurements of the pain experienced, allowing researchers to compare direct pain responses and placebo responses. Although all three creams were identical and inert, in the conditioning phase, each cream was paired with different intensities of the painful stimulus. This design set up expectations in the minds of the participants of the effect of each cream, such that the strong cream had the best pain relief. In a subsequent test phase, the three creams were administered with the exact same intensity of painful stimulus, the participants continued to respond as in the conditioning phase, i.e., the strong cream showed signs of better pain relief compared to the control and weak cream (Fig. 1) (Nakamura et al., 2012).

Although the experiments conducted above might create a sense that your mind is playing tricks on you and cast doubt on your experiences, researchers have been able to identify underlying mechanisms in the brain associated with placebo responses. Most of the time, pain comes from an external sensory experience like pricking your finger or a paper cut, but in addition to the external sensation, the brain also modulates the experience of pain internally. While several areas of the brain are implicated in responding to pain, researchers have identified a specific pathway that originates in the periaqueductal grey (PAG) region in the midbrain. The PAG sends signals down through the brainstem to spinal cord neurons that sense painful stimuli and change their activity through neurochemicals (Wager and Atlas, 2015). Some of these neurochemicals, endogenous opioids, originate internally but are similar in structure to the drug morphine and function as internally generated pain-relief. Neuroimaging studies related to opioid activity in the brain have found increased opioid activity in the PAG associated with placebos. Additionally, placebo effects are reduced by blocking endogenous opioid activity, showing that the internal opioid system plays a key role in mediating placebo effects (Levine et al., 1978). Research on placebos and their impact on pain reveals that our thoughts and the environment surrounding medical treatment can influence our subjective experience through biological pathways. This gives some weight to the idea of mind over matter!

You gotta believe …

The conditioned responses that are observed with placebos are not restricted to the medical world. If you think about it, we all hold certain ideas or beliefs about the world around us. We predict the outcomes of any activity based on prior experience or on information available (for example, “if I run four miles, I’ll be tired”, or “if I eat a big meal, I’ll be full”). While placebos involve physical devices or drugs that come with certain expectations, a belief is simply a set of rules, expectations or the mindset we have about a concept or activity and are developed through learning. Beliefs and the physical effects of beliefs have been best studied in the mindset surrounding the effects of physical activity/ exercise and food on health.

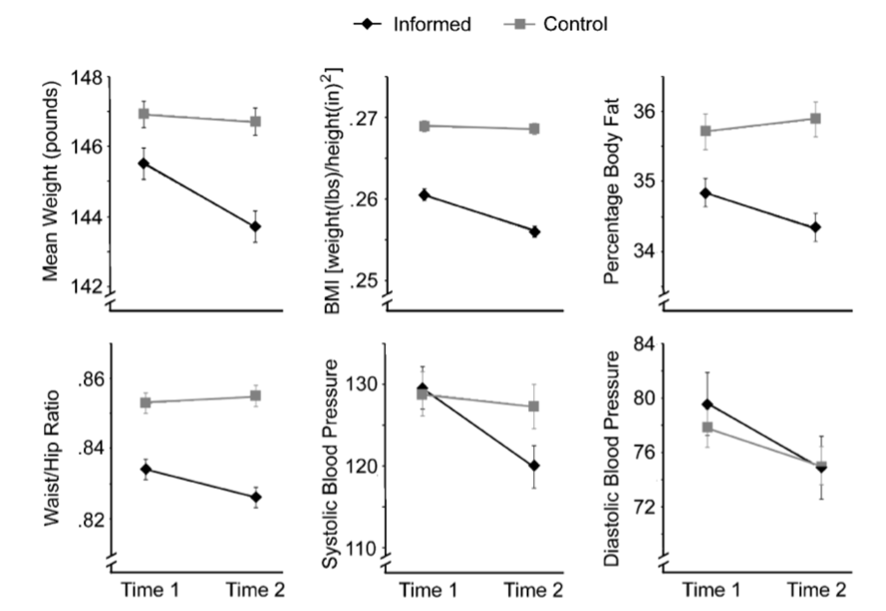

The impact of mindset on the benefits gained from exercise was studied in a group of female hotel attendants (Crum and Langer, 2007). Participants were measured on physiological health variables such as weight and blood pressure. The participants were divided into two groups: the informed condition and the control condition. In the informed condition, participants were given examples of how their day-to-day job provides them with exercise and fulfils the weekly recommendation for physical activity. The control group was not provided this information. Participants were then assessed after four weeks. While the level of activity, as reported by the participants and measured in terms of hours worked, did not change in either group, the informed group perceived themselves to be exercising and compared to controls, showed a decrease in weight, blood pressure, percentage body fat, waist-to-hip ratio, and body mass index (Fig. 2) (Crum and Langer, 2007). In addition to the actual physical activity that these participants performed, their expectations of its effects played a significant role in the health outcomes observed. A caveat to this study is that the actual physical activity was not objectively measured and further research that uses activity trackers are required to confirm the effect. Still, the study does demonstrate that like the placebo, the effects of exercise are influenced by the beliefs surrounding its impact, implying that believing a program will work is a key determinant to success in a fitness program.

Mind over milkshake …

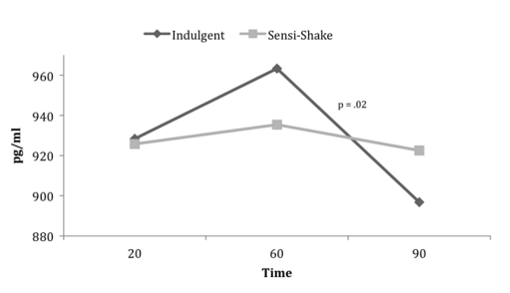

In another study from the same group, beliefs about nutrition and how it influences hunger and satiety were addressed (Crum et al., 2011). The gut-peptide ghrelin is a hunger hormone that increases as you get hungry and rapidly declines after meals with satiety. In this study, participants were given a milkshake on two separate occasions. On one occasion participants were told that the milkshake was a highly indulgent 620 Calorie shake, while on the other occasion they were told it was a healthy 140 Calorie shake. In reality, the milkshake was a standard 380 Calories. Participants’ ghrelin levels were measured before and after the shake. Surprisingly, when participants consumed what they thought was the high calorie shake, their ghrelin levels showed a dramatic steep decline. With the healthy shake, their levels stayed steady and produced a relatively flat curve even though the shake itself didn’t change (Fig. 3) (Crum et al., 2011). This study revealed that participants considered the indulgent shake to be more satiating compared to the healthy one and their perception of the nutritional properties of the shake could change their biological response to it.

Due to the broad nature of its downstream effects, the mechanisms through which mindset influences biological outcomes are hard to define. However, the research described above underscores that our beliefs, expectations, and mindset have far-reaching effects in various aspects of life. Just like the conditioned response to placebos, where prior experiences shape our reactions to inert substances, our beliefs about exercise and nutrition can profoundly influence their actual effects on our bodies. Belief effects and the placebo effect are a fascinating demonstration of how our minds shape our reality, leaving us wondering about the untapped potential of mind over matter. So, while we may not have Jedi-like powers to bend the universe, the impact of our thoughts on our experiences remains a powerful force to explore and harness through life!

References:

- Crum, A.J., Corbin, W.R., Brownell, K.D., and Salovey, P. (2011). Mind over milkshakes: mindsets, not just nutrients, determine ghrelin response. Health Psychol 30, 424-429; discussion 430-421.

- Crum, A.J., and Langer, E.J. (2007). Mind-set matters: exercise and the placebo effect. Psychol Sci 18, 165-171.

- Czerniak, E., and Davidson, M. (2012). Placebo, a historical perspective. European Neuropsychopharmacology 22, 770-774.

- Levine, J.D., Gordon, N.C., and Fields, H.L. (1978). The mechanism of placebo analgesia. Lancet 2, 654-657.

- Nakamura, Y., Donaldson, G.W., Kuhn, R., Bradshaw, D.H., Jacobson, R.C., and Chapman, R.C. (2012). Investigating dose-dependent effects of placebo analgesia: A psychophysiological approach. PAIN 153.

- Pardo-Cabello, A.J., Manzano-Gamero, V., and Puche-Cañas, E. (2022). Placebo: a brief updated review. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 395, 1343-1356.

- Planès, S., Villier, C., and Mallaret, M. (2016). The nocebo effect of drugs. Pharmacol Res Perspect 4, e00208.

- Wager, T.D., and Atlas, L.Y. (2015). The neuroscience of placebo effects: connecting context, learning and health. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 16, 403-418.

Image credit:

You must be logged in to post a comment.