August

13

August

13

Tags

Food for Thought: Docosahexaenoic Acid

We live in an era of self-improvement. With platforms like TikTok and Instagram readily accessible, younger generations can easily scroll through videos of influencers vouching for the next “life-changing” health hack. From pill supplements to mineral sprays, it seems that the opportunities to make a more productive, attractive version of yourself are endless. As work continues to build and the school year approaches, people eagerly seek ways in which they can change their diet to improve cognitive skills. The seemingly unlimited access to anecdotal advice, expert tips, and research studies can become overwhelming; thus, I have generated a “brain food guide” mini-series as an attempt to explain why certain nutrients can improve cognitive function.

Disclaimer: This series will only discuss direct effects of certain nutrients on brain function; however, these molecules have additional effects on the cardiovascular, muscular, and immune system that should be further considered before adding to your diet.

Feeding the Brain

Before diving in, we need to understand how the brain obtains nutrients from the food we eat. Digestive enzymes in the stomach and intestines break down foods into smaller molecules that can be absorbed into the bloodstream [1]. In order for nutrients from the bloodstream to integrate into the brain, they must be able to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB)—a semipermeable lining of cells that controls the passage of molecules between the blood and brain [2]. As we progress through the series, we will keep in mind this food-to-brain pathway to determine which source of nutrient intake is most effective for improving cognitive function.

Spotlight Nutrient: Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA)

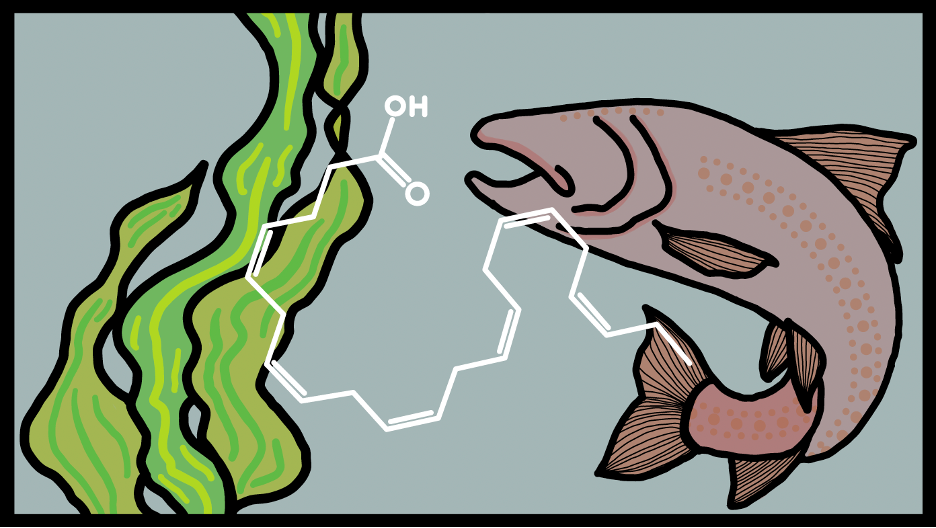

Within the world of nutrition, fatty fish such as salmon or tuna often come up as beneficial dietary additions due to their high content of omega-3 fatty acids—polyunsaturated fatty acids that are classified as “healthy fats” due to their complex molecular structure. There are three main types of omega-3 fatty acids involved in human cellular processes: a-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Of the three, DHA is the most abundant in neuronal tissue; it makes up roughly 40% of total fatty acids in the brain and is unable to be synthesized by humans, making it a critical dietary nutrient [3,4]. While ALA is found in a variety of plants, EPA and DHA are predominately synthesized in algae and plankton [5]. Therefore, fish that consume these marine organisms and contain high lipid stores are optimal sources of DHA.

DHA deficiency has been linked to cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and other brain disorders [6]; thus, several studies have evaluated the effects of DHA supplements on memory and neuronal aging in mice and humans. AD mice that received chronic administration of DHA-containing food presented with reduced learning and memory impairments while also displaying amelioration of depression and anxiety-like behaviors [7]. In the United Kingdom, researchers conducted a randomized controlled trial of DHA intervention in healthy children that were initially underperforming in reading and found that DHA improved literary performance in the poorest reading subgroup and reduced ADHD-like symptoms [8]. Elderly populations with higher DHA consumption and serum levels have also correlated with lower risk of cognitive decline [9,10,11]. Taken together, these studies support the importance of DHA in proper brain function.

Keeping the Membrane Fluid

DHA clearly has an impact on cognitive abilities, but how does this fatty acid impact cellular function? Various cognitive functions depend on the formation and stabilization of synapses—the junctions between neuronal cells that allow for intercellular communication via chemical or electrical signals. Synaptic plasticity, or a neuron’s ability to change the strength of a given synapse, acts as a critical component of learning and memory consolidation; thus, enhancing this phenomenon can lead to improved cognitive abilities [12]. Two central mechanisms contribute to synaptic function and stability: membrane fluidity and neurotransmission.

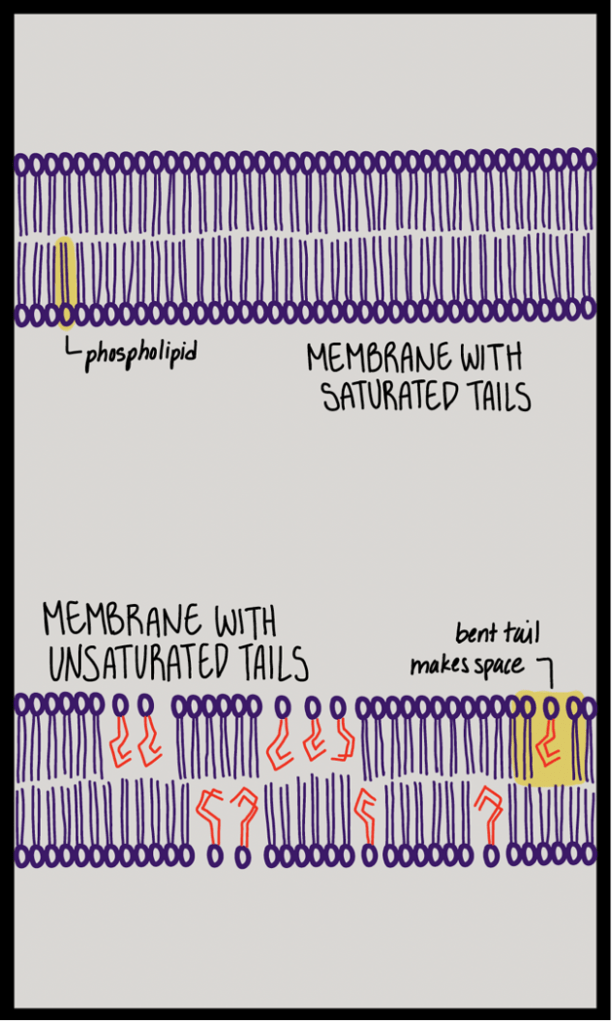

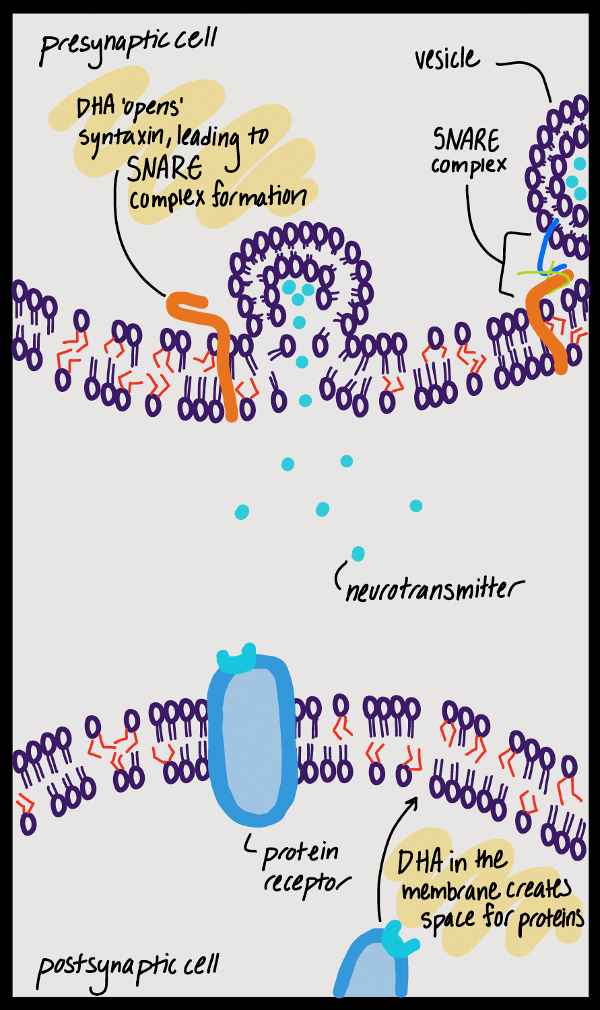

Cell membranes consist of phospholipids that control the passage of molecules and protect the cell’s internal components. Due to their molecular structure, phospholipids can alter the fluidity of membranes; if the lipid tail is larger and has more bends, then the molecules of the cell membrane cannot fit as tightly together, leaving more space for movement [Figure 1]. This becomes particularly important when considering the release and binding of neurotransmitters—signaling molecules that trigger or inhibit neuron activity. Typically, neurotransmitters are stored in vesicles that will fuse with the cell membrane, allowing for the release of its molecular components into the extracellular space. If the cell membrane is more fluid, vesicles can fuse faster, thus increasing the speed a presynaptic neuron can manipulate postsynaptic neurons. Once neurotransmitters are released, they bind with proteins embedded in postsynaptic neuron membranes to generate a downstream response. Neurons can change the density of these proteins depending on the frequency and strength of neurotransmitter release. If the membrane is more fluid, speed of protein insertion and removal increases, leading to heightened levels of plasticity. DHA is incorporated into phospholipids that make up the cell membrane and increases the overall phospholipid content of synaptic plasma membranes, leading to increased membrane fluidity at the synapse [13]. Transmembrane DHA also enables the formation of SNARE complexes, molecular structures that facilitate the fusion of synaptic vesicles to cell membranes, allowing for faster neurotransmitter release [Figure 2; 14]. Thus, this fatty acid acts as an active component of synapse function and can enhance synaptic plasticity in brain circuits associated with learning and memory.

Mode of Consumption

As mentioned prior, nutrients must be able to pass through the BBB to access the brain. Many DHA supplements convert to free DHA by pancreatic enzymes and are absorbed as triacylglycerol (TAG) by adipose tissue, whereas the brain preferentially absorbs DHA in the form of lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) [15]. When mice were treated with LPC-DHA versus free DHA, the mice receiving LPC-DHA had higher enrichment of DHA in brain tissue and displayed enhanced spatial learning and memory compared to mice receiving free DHA [15]. Thus, DHA supplements containing LPC may be more effective at improving cognitive function while free DHA supplements may be more effective at improving cardiovascular health. Natural sources of LPC-DHA include fatty fish and seafood (salmon, herring, oysters, etc.), while supplements in the form of fish and krill oils with added LPC are only available for preclinical studies. Algae oils can function as a vegan-friendly DHA source; however, these do not contain added LPC. As additional research involving the cognitive effects of free DHA versus LPC-DHA progresses, access to a greater variety of supplement options will likely ensue.

Up Next…

You have likely heard the term antioxidant when considering improving nutrition…but what does this mean? Stay tuned to learn more about this family of nutrients and their biochemical implications on neuronal health.

References

[1] Kiela, P. R., & Ghishan, F. K. (2016). Physiology of Intestinal Absorption and Secretion. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology, 30(2), 145–159. 10.1016/j.bpg.2016.02.007

[2] De Rus Jacquet, A., Layé, S., & Calon, F. (2023). How nutrients and natural products act on the brain: Beyond pharmacology. Cell Reports Medicine, 4(10), 101243. 10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101243

[3] Tanaka, K., Farooqui, A. A., Siddiqi, N. J., Alhomida, A. S., & Ong, W.-Y. (2012). Effects of Docosahexaenoic Acid on Neurotransmission. Biomolecules and Therapeutics, 20(2), 152–157. 10.4062/biomolther.2012.20.2.152

[4] Dighriri, I. M., Alsubaie, A. M., Hakami, F. M., Hamithi, D. M., Alshekh, M. M., Khobrani, F. A., Dalak, F. E., Hakami, A. A., Alsueaadi, E. H., Alsaawi, L. S., Alshammari, S. F., Alqahtani, A. S., Alawi, I. A., Aljuaid, A. A., & Tawhari, M. Q. (2022). Effects of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Brain Functions: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 10.7759/cureus.30091

[5] Omega-3 Fatty Acids. (2023, February 15). National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS). https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Omega3FattyAcids-HealthProfessional/#en3

[6] Bazan, N. G., Molina, M. F., & Gordon, W. C. (2011). Docosahexaenoic Acid Signalolipidomics in Nutrition: Significance in Aging, Neuroinflammation, Macular Degeneration, Alzheimer’s, and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases. Annual Review of Nutrition, 31(1), 321–351. 10.1146/annurev.nutr.012809.104635

[7] Xiao, M., Xiang, W., Chen, Y., Peng, N., Du, X., Lu, S., Zuo, Y., Li, B., Hu, Y., & Li, X. (2022). DHA Ameliorates Cognitive Ability, Reduces Amyloid Deposition, and Nerve Fiber Production in Alzheimer’s Disease. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9, 852433. 10.3389/fnut.2022.852433

[8] Richardson, A. J., Burton, J. R., Sewell, R. P., Spreckelsen, T. F., & Montgomery, P. (2012). Docosahexaenoic Acid for Reading, Cognition and Behavior in Children Aged 7–9 Years: A Randomized, Controlled Trial (The DOLAB Study). PLoS ONE, 7(9), e43909. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043909

[9] Kalmijn, S., Van Boxtel, M. P. J., Ocké, M., Verschuren, W. M. M., Kromhout, D., & Launer, L. J. (2004). Dietary intake of fatty acids and fish in relation to cognitive performance at middle age. Neurology, 62(2), 275–280.

[10] Gao, Q., Niti, M., Feng, L., Yap, K. B., & Ng, T. P. (2011). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplements and cognitive decline: Singapore longitudinal aging studies. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 15(1), 32–35. 10.1007/s12603-011-0010-z

[11] Otsuka, R., Tange, C., Nishita, Y., Kato, Y., Imai, T., Ando, F., & Shimokata, H. (2014). Serum docosahexaenoic and eicosapentaenoic acid and risk of cognitive decline over 10 years among elderly Japanese. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 68(4), 503–509. 10.1038/ejcn.2013.264

[12] Goto, A. (2022). Synaptic plasticity during systems memory consolidation. Neuroscience Research, 183, 1–6. 10.1016/j.neures.2022.05.008

[13] Shahdat, H., Hashimoto, M., Shimada, T., & Shido, O. (2004). Synaptic plasma membrane-bound acetylcholinesterase activity is not affected by docosahexaenoic acid-induced decrease in membrane order. Life Sciences, 74(24), 3009–3024. 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.028

[14] Walczewska, A., Stępień, T., Bewicz-Binkowska, D., & Zgórzyńska, E. (2011). Rola kwasu dokozaheksaenowego w czynności komórek nerwowych. Postępy Higieny i Medycyny Doświadczalnej, 65, 314–327. 10.5604/17322693.945763

[15] Sugasini, D., Thomas, R., Yalagala, P. C. R., Tai, L. M., & Subbaiah, P. V. (2017). Dietary docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) as lysophosphatidylcholine, but not as free acid, enriches brain DHA and improves memory in adult mice. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 11263. 10.1038/s41598-017-11766-0

You must be logged in to post a comment.