August

22

August

22

Tags

The Science of Sensitivity

Insights from the Neuroscience of Highly Sensitive People

I am driving home as the sun beams through the windshield and straight into my face. It’s beautiful: the orange glow of the golden hour sky, the demanding brightness seen through squinted eyes. But it also adds to my dread about the half-an-hour of incoming stop-and-go traffic. Clutch break. Gas. Clutch break. Gas. My mind is stirring, darting around to the tasks and worries and conversations from the day. The drum of the music in the car next to me feels like it’s beating inside my head. Clutch break. Gas. I adjust the sun visor. I think about how it feels like it’s been too long since I’ve last called to catch up with old friends in other cities and how I really should do that to show that I care. Drum drum. My mind flashes to – Clutch break. Gas – that meeting I had earlier (dang, it’s bright in here), going over all the to-dos, and the have-dones – drum drum – and how I tripped in the hallway walking to the printer, maybe I should …

Rest.

I first heard the term “Highly Sensitive People” in therapy. I clearly remember the moment of recognition that I am one of these people. Someone who has a higher sensory processing sensitivity. This means that a person’s central nervous system responds at a lower threshold to stimulation than most people. This makes them more sensitive to environmental stimuli, both positive (like praise from a teacher or an extra soft blanket) and negative (such as car horns honking their disapproval and ill-fitting shoes).

High sensitivity is not a diagnosis but rather a temperament. It is something you walk through life with that affects what you pay attention to and how you interpret and process the world around you. Notably, it’s not all that rare. 15-20% [1] of people are Highly Sensitive.

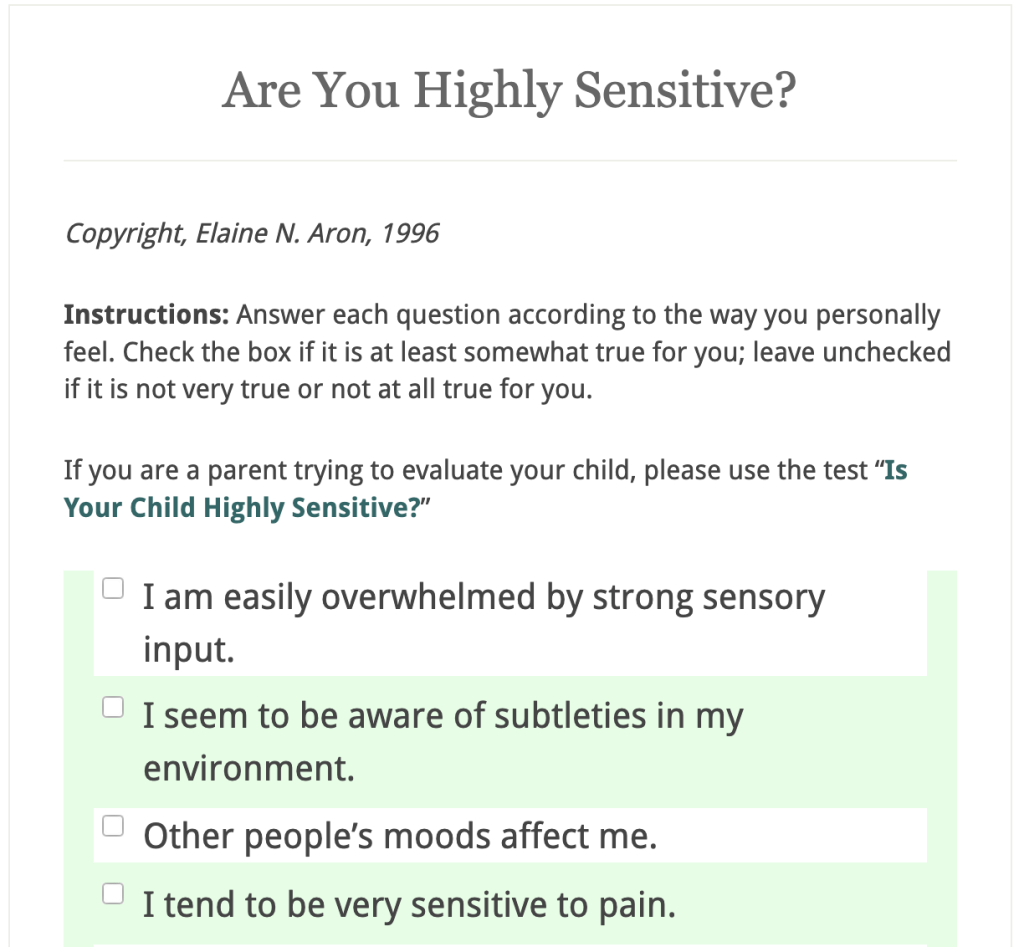

Psychologist and author Dr. Elaine Aron has dedicated her career to researching and discussing the trait of high sensitivity. She describes Highly Sensitive People (HSP) as having four distinct characteristics [1]:

1) Increased depth of processing: HSPs tend to think deeply about the meaning of life, find making decisions difficult, are perfectionistic, and are highly conscientious.

2) Overstimulation: They need more downtime to recover from a highly stimulating day and need decreased stimulation to perform. Their optimal level of arousal is lower than that of the average person.

3) Emotional responsiveness: They tend to have greater empathy and feel emotions before other people do.

4) Sensitiveness to subtleties: They are more aware of subtle environmental cues, such as scents, beautiful scenes, and emotional cues. They are intuitive and observant.

Dr. Aron developed the “HSP Scale” questionnaire to determine whether someone is highly sensitive. You can preview the assessment to the right and take it yourself here [2].

Reading Dr. Aron’s description of an HSP resonated with me. I could see myself in these questions and recognize that many more people function the same way that I do. This was a satisfying realization, but it also raised many more questions.

How can the same environmental cues—an identical shout from a friend across the street or bright fluorescent light in a lecture hall—cause different responses for highly sensitive and not-highly sensitive folks? Do their brains actually respond differently? Are there observable biological explanations?

Highly Sensitive Brains

It so turns out that there are distinct physiological differences in the brain function of Highly Sensitive People.

One way researchers characterize brain function is through functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a noninvasive neuroimaging technique that measures changes in blood flow as a marker for neural activity. Several studies have used this technique to investigate differences in neural activity in HSP individuals. One study had participants view images of their romantic partner and a stranger, making positive, neutral, and negative facial expressions. The scientists found that people who scored higher on the HSP scale showed increased activation in brain regions involved in awareness, integration of sensory information, empathy, and action planning compared to those who scored lower on the scale [3]. The authors emphasized that activation of regions involved in attention and action planning, namely the cingulate cortex and the premotor area, are positively associated with HSP scores across all conditions in the study. They replicated this result in a second scan a year later. This provides evidence that highly sensitive brains are primed to attune to and respond to sensory stimuli of any valence, such as a partner laughing or a stranger scowling. Highly sensitive brains even respond differently to changes in visual scenes. A study from 2011 showed that individuals with a higher HSP score showed greater activation in brain regions involved in high-order visual processing [4]. In other words, their visual system was more responsive than other individuals to the same visual cues. These two studies show distinct functional differences associated with high sensitivity and provide evidence that awareness and responsiveness are innate features of highly sensitive brains.

Functional differences have also been observed using electroencephalography or EEG, which measures electrical activity within the brain. Of the 115 participants in the study, the lowest and highest 30% of HSP scores were compared. The researchers found that the high-HSP group had increased brain activity during a resting state (including higher beta power, gamma power, and global EEG power) compared to the low-HSP group while subjects had their eyes open [5]. Interestingly, while subjects had their eyes closed, there was no difference in activity. This study supports the central hypothesis that HSPs have enhanced information processing since their brains are more active during a resting state.

It is important to note that the high-sensitivity field is relatively young, and there is still so much unknown about how highly sensitive brains differ, including what specific genes or biological processes contribute to the trait. One twin study (which are often used to compare the genetic and environmental influence on traits) found that genetic influences account for 47% of environmental sensitivity [6]. It is still unclear, however, which specific genes may contribute to the high sensitivity trait, and how this mechanism promotes different neural responses.

As a whole, these studies point to general brain regions that should be further investigated, and provide evidence for increased physiological activity in HSP brains. There are still relatively few studies investigating high sensitivity, and many of the ones that do have fairly small sample sizes, or are affected by other limitations such as biological sex of subjects (some studies had more women in the high-HSP category and more men in the low-HSP category). More women than men identify as highly sensitive, and it is unclear the relative weight of biological and social context on this distribution. There is still so much to learn about the biology and the psychology that plays into the complex trait of sensitivity.

Cultural Context of High Sensitivity

It is impossible to talk about sensitivity as a trait without acknowledging that it is viewed and developed differently depending on cultural context. For instance, Western and more individualistic cultures tend to value high-arousal emotions and extraversion compared to Eastern and more collectivist cultures. This means that HSPs growing up in a Western culture might be more encouraged to hide aspects of their sensitivity.

It is important to say, though, that sensitivity is not the same as introversion. There are many possibilities for combinations of traits including sensitivity, sensation-seeking, and extraversion or introversion. Maybe you are highly sensitive but seek high intensity sensations and experiences, for example climbing mountains. You can enjoy the sensation, the effort of the climb and the hot sun on your face and the grit that it takes to trudge up and up and up … the stimulation and the arousal. But you can also enjoy the solitude and introversion of the experience, the rustle of the leaves, the stillness, the silence that emphasizes every breath you take. The high sensitivity may lead to greater reflection upon and meaning derived from the experience [7].

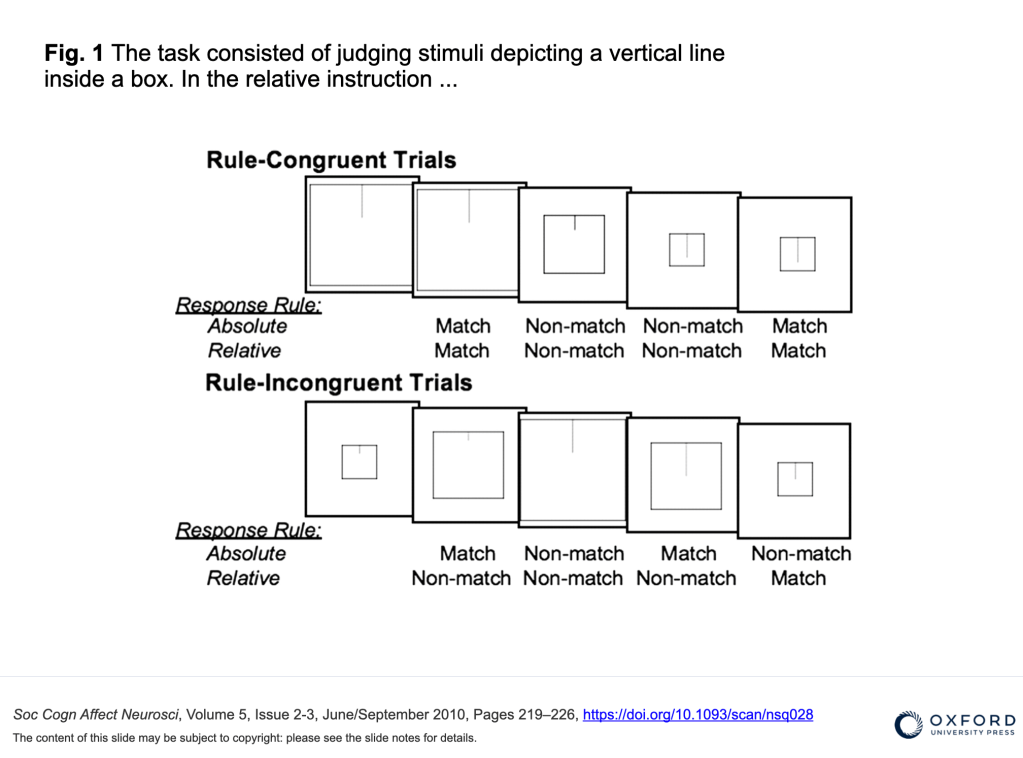

High sensitivity can also impact culturally dependent neural responses. A study from 2008 [8] identified a cultural difference in neural response to a context-dependent or context-independent visual task. The study showed that European-American subjects typically found the context-independent task easier, while East Asians typically found the context-dependent task easier. The context-dependent (relative) task involved judging whether a box and line combination matched the proportional scaling of the preceding combination. The context-independent (absolute) task involved judging whether the current line matched the previous line. Both groups showed increased neural activation while performing the culturally non-preferred task. This indicates that cultural background influences the neural activity behind cognitive tasks. Fascinatingly, when data from this study was re-analyzed to investigate how high sensitivity influences the results, researchers found that those with higher HSP scores had little cultural difference in neural response compared to low HSP scores, who had large differences in cultural response. This finding indicates that some people’s neural activity is less influenced by cultural context. The researchers suggested that this is because HSPs process all stimuli more thoroughly; therefore, their judgments may be more heavily based on the actual stimuli than for others without the trait [9].

Promoting Well-being for HSPs

Like most traits, high sensitivity has both positive and negative aspects. Just as honesty can make one trustworthy and brutal, sensitivity can make one empathetic and easily hurt. Ultimately, the goal is to acknowledge your temperament and learn how to exercise your skills and manage your struggles, whatever they may be.

A qualitative study interviewing many HSPs about their well-being found some specific practices and perspectives to help HSPs thrive. They emphasized harmony across many dimensions of life as essential. They described the importance of pursuing “low-intensity positive emotion, self-awareness, positive social relationships balanced with times of solitude, connecting with nature, contemplative practices, emotional self-regulation, practicing self-compassion, having a sense of meaning, and hope/optimism” [10]. I have found that incorporating these practices in my own life has helped me cope in a stimulating environment and made my life so much richer and more meaningful.

High sensitivity might lead to a richer internal world and life experience, but it can also lead to increased struggles with overstimulation. It is important to remember that high sensitivity or not, both types of people are essential and important to our world and offer valuable and unique skills and perspectives.

References

- https://hsperson.com/

- https://hsperson.com/test/highly-sensitive-test/

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/brb3.242

- https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/sbp/sbp/2016/00000044/00000002/art00002

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2023.1200962/full

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-020-0783-8

- https://www.goodlifeproject.com/podcast/elaine-aron-phd-highly-sensitive-people/

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02038.x?casa_token=MtvbO6mXrPwAAAAA%3AkiqaLWkdgykQewFMkq1qbkU8IgVz9MwyBsR6YhyfQ43HQZpbmn0ne1vaN43jKKpmERyAVWDriIBy0Q

- https://academic.oup.com/scan/article/5/2-3/219/1659287

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-020-0482-8

You must be logged in to post a comment.