October

31

October

31

Tags

The Double-Edged Sword of Cellular Senescence

To Divide or Not to Divide, That is the Question

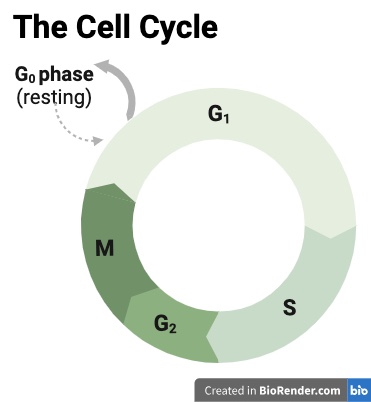

You might remember learning about the cell cycle in high school biology class. This is the process where cells in the human body divide to reproduce.

This cycle contains four distinct phases, which you can see in the image to the right. In the first, called G1, the cell grows in size; in the second, called Synthesis, it makes copies of its DNA, the genetic instructions for making more cells; in the third, called G2, it prepares to divide; and in the fourth, called Mitosis, it splits into two identical daughter cells [1].

Some cells in our bodies stay in this cycle of constant renewal throughout our lives, such as those in the skin or the intestines. Things we touch and eat often damage these tissues, so they must constantly produce new cells to regenerate. In other parts of our bodies, cells do not reproduce at all once they reach maturity. This includes the neurons that send information across our brains and bodies, and the cardiomyocytes that enable the contracting and relaxing of our beating hearts. These mature cells are called post-mitotic cells since they will no longer undergo mitosis.

There are other reasons, too, that a cell may leave the cell cycle temporarily or permanently. This includes quiescence [2-3], which can be thought of as a waiting phase, where the cells do not actively divide but can quickly re-enter the cell cycle if needed. Cells also leave the cell cycle if they are subject to damage or stress. If the damage is repairable, cells can temporarily pause the cell cycle to mend, then re-enter it and continue to divide.

When the harm is too severe to repair, such as when the DNA is significantly damaged or reactive molecules have wreaked havoc on cellular components, cells may undergo one of two processes: apoptosis, a form of pre-programmed cell death, or enter senescence, a permanent non-dividing state. Whether a cell undergoes apoptosis or senescence depends on various factors, including the severity of the damage, the type of cell it is, and whether specific cellular stress pathways are activated.

Senescence has become a hot topic in scientific research in recent decades because of both its positive and negative implications for aging, health, and disease development.

Too Stressed, Gotta Senesce

Leonard Hayflick first identified senescence in the 1960s. While growing human cells in a petri dish, he observed that the dividing cells could only replicate so many times before they stopped being able to.

Upon further investigation, he found that the ends of their DNA, a region called the telomeres, get shortened each replication. This is because the cellular machinery responsible for replicating the DNA in preparation for cell division does not allow the entire molecule to be copied. Instead, the DNA loses around 50-200 base pairs (the individual DNA units) from the telomere region at every replication [5]. Eventually, the telomeres become too short, and the cell enters senescence. This phenomenon, which is that human cells have a limited capacity to divide, after which they become senescent, is called the Hayflick limit [6].

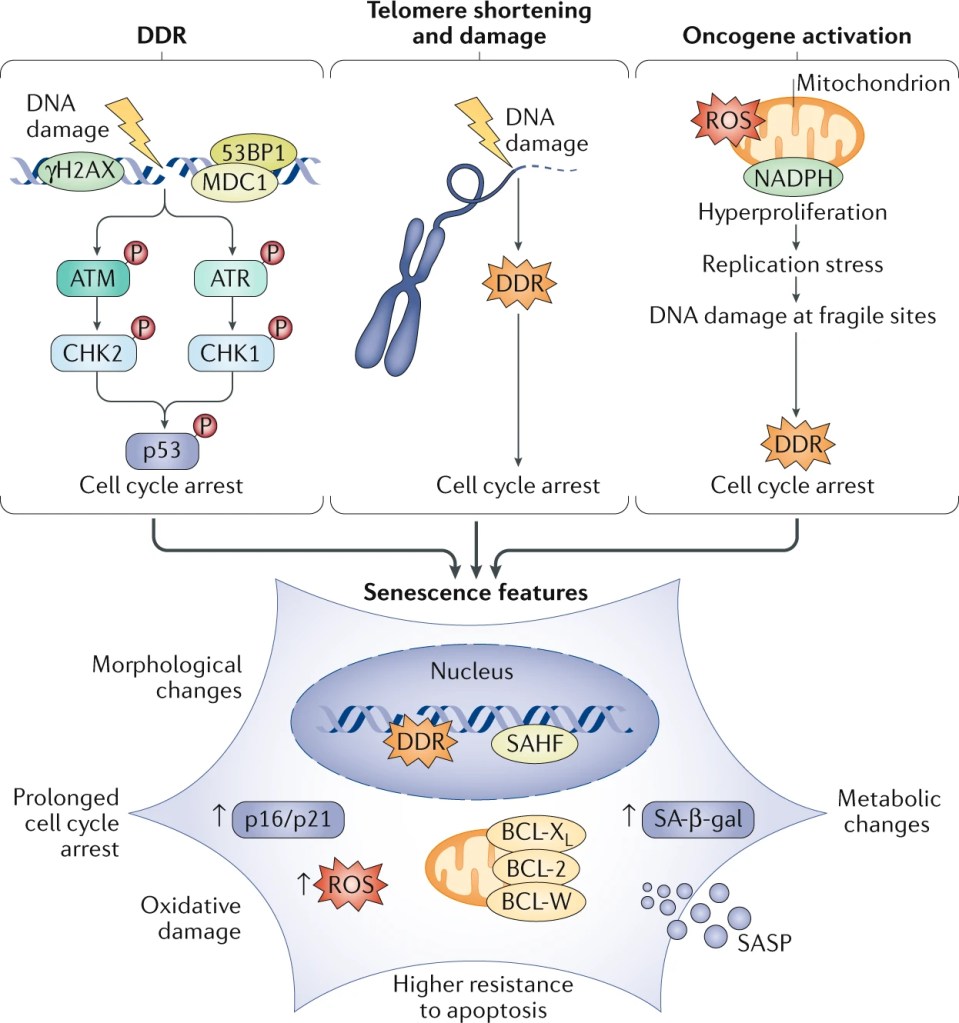

Telomere shortening isn’t the only reason that cells enter senescence, though. Cells that have undergone severe stress, such as damage to their DNA or activation of certain cancer-causing genes called oncogenes, often enter senescence as well.

Senescence is a preserved cellular process with specific features:

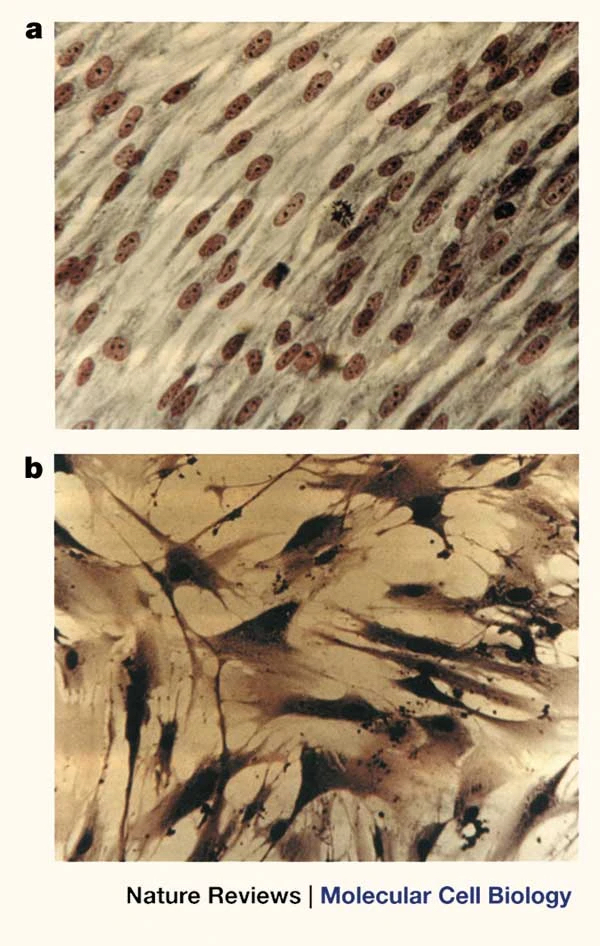

- Changes in shape: Cells appear large and flat.

- Cell cycle arrest: Cells stop dividing.

- Loss of physiological function: Organelles or cellular compartments providing essential functions, such as the energy-producing mitochondria and the digestive lysosome, become dysfunctional.

- Secretory response: Cells release molecules that influence the inflammatory response, the immune system, and architecture of body tissues called the Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) [4].

While it was first assumed that only dividing cells could enter senescence, scientists more recently figured out that post-mitotic cells that undergo stress, such as the neurons and cardiomyocytes described earlier, can also enter senescence [7].

Senescence as a Healer

Senescence is a double-edged sword with positive and negative implications for human health. On the bright side, senescence contributes to wound healing and regeneration.

Imagine you are hiking in the forest, trip over a tree root, and cut your knee on a rock. Your immune system and wound healing response kick into high gear. This includes many cellular processes, including swelling to increase blood flow to the wounded area and white blood cells infiltrating the tissue, cleaning up debris and intruding microorganisms. As the days go by and the cut undergoes the healing process, skin cells, called fibroblasts, must replicate to repair the wound.

There is a limit to the amount of replication before the fibroblasts produce an overabundance of sticky proteins that live in the space between cells. This replacement of functional tissue with excess fibrous connective tissue is called fibrosis [8]. Fibrosis can lead to extreme consequences such as organ failure. To prevent this, some fibroblasts in the wound-healing environment are triggered to enter senescence. Not only does this reduce the excess accumulation of cells that lead to fibrosis (since senescent cells no longer undergo cell division), but the senescent fibroblasts also release inflammatory molecules through the SASP response that help attract immune cells to the wound site and promote the formation of new blood vessels [9], all of which contribute to proper wound healing.

Senescence also plays an essential role in tissue regeneration and embryonic development [10]. Studies in diverse animals, from fish and amphibians to mammals, have identified roles of senescent cells [11]. In fish, for example, senescent cells are necessary to regenerate an amputated fin [12]. Senescent cells are also essential for embryonic development, where they help control growth and patterning in the placenta of mammals and shape body growth in amphibians [4].

One of the other centrally recognized roles of cellular senescence is cancer prevention. Cells with DNA damage are more likely to become oncogenic (cancer-causing), and entering senescence forces these cells to exit the cell cycle, thus preventing uncontrolled cell division and tumor initiation [3].

In these circumstances, cellular senescence is part of normal development, repair, and maintenance of healthy body tissues. But senescent cells have a dark side as well.

Senescence as a Harmer

Senescence is infamous for contributing to aging and age-related diseases. In fact, it has been studied far more extensively in its disease-associated roles than in its contributions to healthy body function.

Even in the case of cancer, as described above, it’s not all rainbows and butterflies. While the exit from the cell cycle prevents tumor initiation, the chronic inflammation driven by the SASP response has been shown to support tumor growth [13].

As humans age, the body’s tissues tend to become more inflamed. This increased presence of angry inflammatory molecules circulating in the blood due to aging, also called inflammaging [14], is a risk factor for many age-associated diseases such as cancer, neurodegeneration, and cardiovascular disease.

The accumulated stress that cells in your body undergo throughout time drives more cells into senescence as you age. These cells that are initially stressed and enter senescence produce the SASP response, which can also trigger other cells to enter senescence, visualized by the image to the right. The amplification of this response is thought to contribute to chronic inflammation [15] and metabolic dysfunction, ultimately accelerating frailty and disease.

One study even found that senescent cells cause frailty and reduced lifespan by putting senescent cells into mice and observing increased tissue dysfunction and shortened lifespan compared to mice that received non-senescent cells [16].

Senescent cells are also known to contribute to neurodegeneration, such as Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuroinflammation, or inflammation in the brain, is a hallmark feature of the disease. In a paper published by scientist (and NeuWrite writer!) Joe Herdy [17] showed that there is a higher proportion of senescent neurons in the brains of individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease than in similarly aged healthy adults. This study shows that this increased proportion of senescent cells in Alzheimer’s brains provides a greater than-normal source of brain inflammation, contributing to the progression of the disease.

In the Clinic

Due to their impact on many diseases, senescent cells have become a popular target while developing new clinical treatments. Scientists developed senolytic therapies to remove senescent cells.

These drugs disable the survival mechanisms that senescent cells use to protect themselves from their own harmful inflammatory environment. With their shield removed, the senescent cells succumb to their own sword and undergo apoptosis [14].

This has led to clinical trials, such as one that began in 2016 [18] that used the senolytic drugs Dasatinib + Quercetin to remove senescent cells in patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, a chronic lung disease. Fourteen patients received nine doses of the drug over three weeks. The results showed some initial evidence that the senolytics might alleviate physical dysfunction, shown through meaningfully improved performance on physical tasks like walking and standing from a chair, but there were no clear improvements in pulmonary function and there was one adverse event [19].

Researchers are planning to perform a larger trial soon, and there are over 20 others that are ongoing or planned [20]. Drugs targeting senescent cells are really in their infancy, and there is a lot more to learn about how the potential side-effects and clinical results of senolytics.

Evolution of Senescence

Senescence appears to be a tightly regulated cellular state. To become so prominent in our bodies, senescent cells must have served some evolutionary purpose and offered some advantage. Attributing senescence as a mechanism to avoid cancer by opting damaged cells out of the cell cycle doesn’t entirely explain it, since senescent cells can also contribute to tumor growth through their SASP response.

Perhaps its functions in wound healing and development were the greater drivers for its evolution. In these processes, senescence appears temporarily and is highly controlled. However, if too many of these cells accumulate or stay around too long, they can lead to severe consequences [21].

The immune system needs to identify senescent cells and get rid of them quickly after they have served their designated purpose. When purging senescent cells from the body, the immune system must ultimately balance missing some senescent cells and killing off too many healthy, non-senescent cells.

Understanding this balance could be the key to harnessing senescence for therapeutic benefit—eliminating senescent cells where they cause harm and maintaining the essential body functions that they support.

References:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7888710/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41581-022-00601-z

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41580-020-00314-w

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2726829/#:~:text=Because%20of%20the%20unidirectional%20nature,and%20De%20Lange%2C%202004).

- https://www.nature.com/articles/35036093

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7821432/

- https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2019.10.004

- https://www.nature.com/articles/ncb2070

- https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(13)01359-7?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS0092867413013597%3Fshowall%3Dtrue

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34181964/

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/acel.13052

- https://www.cell.com/cancer-cell/fulltext/S1535-6108(18)30264-2?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS1535610818302642%3Fshowall%3Dtrue

- https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06651.x

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s43587-021-00121-8

- https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA572757804&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=fulltext&issn=10788956&p=AONE&sw=w&userGroupName=ucsandiego&aty=ip

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36459967/

- https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02874989

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30616998/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-022-01923-y

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0047637421001007?via%3Dihub

Images

You must be logged in to post a comment.