November

21

November

21

Tags

Paresthesia: more than just pins & needles

It happens to us all – you doze off in a less-than-ideal position, and when you awaken, there’s a part of your body that has gone numb. It’s certainly aggravating – your limb is unusable and unresponsive for several moments, flopping about with uncomfortable tingles. Commonly, we complain that our feet, legs, fingers, or arms have ‘fallen asleep’. As the sensation begins to return, it feels like pins and needles, tingling like the human version of TV static. But what actually causes this loss of sensation?

What is paresthesia?

This sensation falls under the umbrella of paresthesia (alternate spelling paraesthesia). This phenomenon’s name has Latin and Greek roots; ‘para’ roughly translates to disordered, and ‘aesthesia’ to perception or feeling (1). Paresthesias occur most frequently in the extremities – hands, arms, legs, and feet – and is not limited to the sensation of numbness. In addition, paresthesias can manifest as tingling and prickling – the ‘pins and needles’ feeling that may ring familiar – as well as itching and burning (2).

Transient tingles

The specific case of paresthesia brought on by uncomfortable sleeping positions is known as obdormition. Simply stated, this sensation of numbness and tingling usually occurs when the blood supply to one of your extremities is cut off. While it might be annoying, the good news is that it typically fades soon after one changes their body position and removes pressure from the limb that has been receiving decreased blood flow (3).

Disrupted circulation in more acute cases – more sudden and severe – can also lead to paresthesia. In cases of arterial occlusion, when an artery is blocked by biological matter such as an embolism or thrombus (a blood clot, air bubble, or other type of obstruction), there can be an emergent need for medical intervention. In some situations, these blockages may be caused by an aneurysm, which occurs when a blood vessel becomes weakened and forms a bulge, impairing circulation (4). In these scenarios, occlusions lead to a classic array of symptoms called the five Ps; pallor (paleness), pain, pulselessness, paralysis, and paresthesia (5). In dire cases, surgical intervention is necessary.

Chronically numb

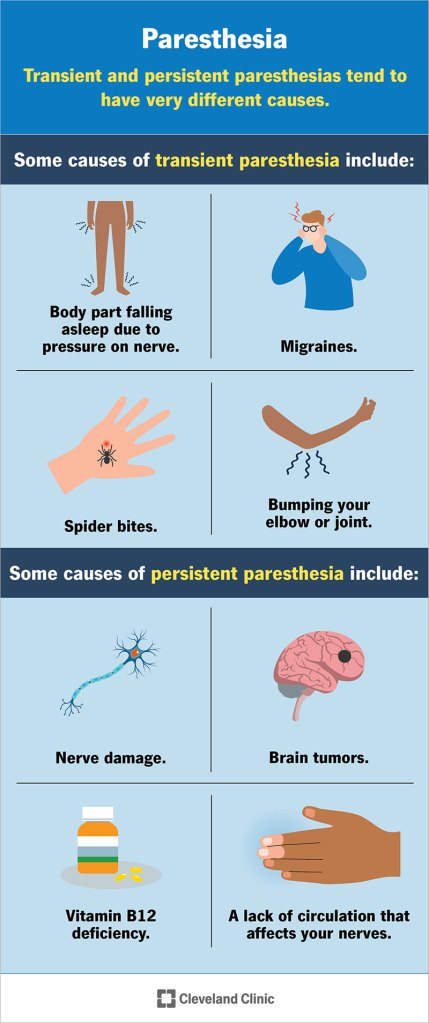

Although most common paresthesias are transient, meaning that they are temporary or fleeting, some cases can be chronic (Figure 1). In cases of chronic paresthesia, unpleasant sensations can persist for much longer periods – hours, days, even months – which can be debilitating (5).

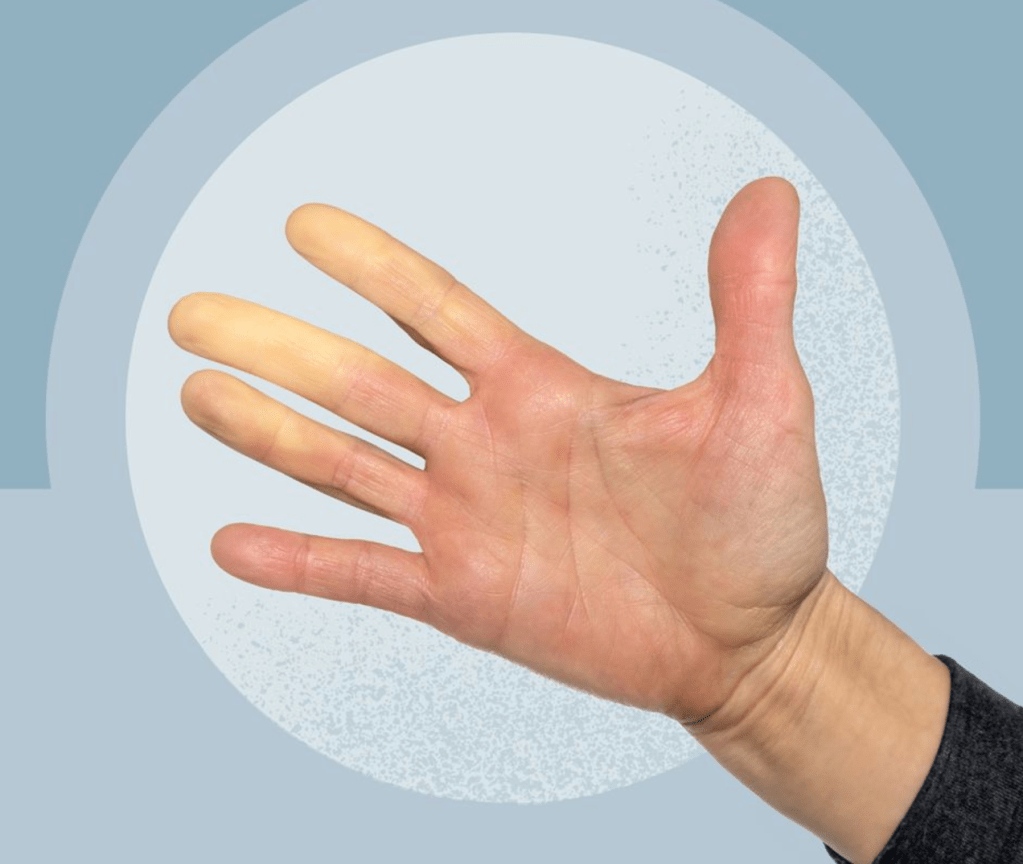

As aforementioned, paresthesia often occurs when circulation is disrupted. To that end, it is very common in circulatory disorders. In a common syndrome known as Raynaud’s disease, patients often have issues with their extremities growing cold and becoming discolored due to insufficient blood circulation (6, image). This disease affects an estimated 5-20% of women and 4-14% of men in the United States, although some studies report lower prevalence (7, 8, 9). Insufficient circulation occurs as a result of a narrowing of the blood vessels that provide blood flow to the skin and often worsens in cold temperatures. Because your fingers and toes are the furthest extremities away from your heart, these are often the body parts that suffer the poorest circulation and are most vulnerable. In addition to these symptoms, Raynaud’s often also brings about paresthesia of the fingers and toes. This can manifest as numbness, or as ‘pins and needles’. Although patients with Raynaud’s experience this paresthesia persistently, it often subsides when warmth is restored to the body.

Research on Raynaud’s disease has aimed to examine the causes underlying circulatory issues. It has been shown that decreased circulation is due to excessive vasoconstriction as a result of exposure to the cold (10). Interestingly, it is thought that this is due to issues with habituating, or changing one’s baseline, to fit changing external stimuli – mainly sensory stimuli like temperature, but interestingly, to other types of stimuli as well. To study this theory, researchers took advantage of a well characterized reaction to new and/or noxious (unpleasant, aversive) stimuli. There is a stereotyped phenotype of this startling response; imagine hearing an unexpected clattering noise – your heart may begin to race, you might even jump a bit and feel your palms start to sweat. The classic reaction importantly includes altered circulatory function dictated by the central nervous system, including an increased heart rate, vasodilation in forearm muscle (broadening of blood vessels), and vasoconstriction (narrowing) in the fingers and skin (10). It was shown that people with and without Raynaud’s both habituated over time to the startling noises at equal speeds, and reported similar levels of discomfort. However, those with Raynaud’s continued to display circulatory phenotypes of the startle response even after their self-reported discomfort had subsided. This indicated that there may be a disconnect in this population’s central nervous ability to habituate to external sensory stimuli, instead maintaining its reactive state of vasoconstriction for disadvantageous lengths of time.

Stuck in a pinch

While circulatory disorders and temporarily deadened circulation account for a majority of transient and chronic paresthesias, another subset of cases of chronic paresthesia can be attributed to peripheral neuropathy. Broadly stated, neuropathy can be defined as damage or disease of the nerves (2). Peripheral specifically refers to nerve damage affecting the peripheral nervous system, the nerves that extend from our spinal cord to innervate our trunk and limbs. Carpal tunnel syndrome is a perfect example of syndromic neuropathy which leads to paresthesia. Carpal tunnel syndrome is the most common type of ‘entrapment neuropathy’ (5) and has been reported as being responsible for up to 90% of neuropathy cases (11). Entrapment neuropathy refers to the phenomenon of a nerve becoming compressed by surrounding bone, which often occurs to the median nerve, running through the carpal bone near the wrist and innervating one’s hand and fingers (Figure 2). In moderate to severe cases of carpal tunnel syndrome, compression can lead to demyelination of the nerve. Nerves are surrounded by a layer of fatty cells called a myelin sheath, responsible for insulating electrical signals through a neuron (12). When this sheath is damaged by demyelinating diseases, a decrease in insulation can cause issues in neural transmission and contribute to sensory and motor issues, such as numbness, ‘pins and needles’, and more (Figure 3).

Chronically frustrating

While carpal tunnel syndrome is highly prevalent and can be difficult to live with, a myriad of other rare types of neuropathy also plague patients with chronic paresthesia. A recent clinical study aimed to assess improvement of paresthesia symptomology following surgical treatment of degenerative cervical myelopathy (DCM; 13). DCM is the most common form of spinal cord nerve dysfunction in adults, and occurs when aging-related changes in bone lead to compression of the spinal cord, particularly in the cervical (neck) region (14). Before and after patients underwent surgery, they were surveyed to assess their experience with paresthesia. Unfortunately, a whopping 45% of patients continued to experience severe paresthesia-related pain one year after surgery (13). This indicated to researchers and clinicians that, even though there were some improvements in the root cause of the DCM, painful paresthesias may require medication and separate treatment if they are not fully addressed by surgical intervention – and it does appear they are often not.

While it may seem like there is a deep breadth of knowledge about paresthesia, our understanding of how to prevent it clinically is actually rather shallow. While scientists and clinicians have characterized its role in many chronic health disorders and conditions, the root causes are quite variable and manifest with varying degrees of severity. Hopefully, with increased understanding of what underlies paresthesia and when it may manifest, improved diagnosis and treatment of chronic cases will become a reality.

Citations

- Online Etymology Dictionary. (2020, August 18). Paraesthesia (n.). Paraesthesia. https://www.etymonline.com/word/paraesthesia

- National Institutes of Health. (2024, August). Glossary of neurological terms. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/glossary-neurological-terms

- NHS. (2024, January). Pins and needles. NHS . https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pins-and-needles/#:~:text=What%20is%20pins%20and%20needles,the%20nerves%20is%20cut%20off

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (2024). Aneurysm. Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/aneurysm

- Sharif-Alhoseini, M., Rahimi-Movaghar, V., & R., A. (2012). Underlying Causes of Paresthesia. InTech. doi: 10.5772/32360

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2024, November 16). Raynaud’s disease. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/raynauds-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20363571

- Temprano K. K. (2016). A Review of Raynaud’s Disease. Missouri medicine, 113(2), 123–126.

- Pope, J. (2014). Primary Raynaud Phenomenon. Am Fam Physician. 90(6):403-404.

- Ling SM, Wigley FM. Raynaud’s phenomenon in older adults: diagnostic considerations and management. Drugs Aging. 1999;15:183. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199915030-00002.

- Cooke, J. P., & Marshall, J. M. (2005). Mechanisms of Raynaud’s disease. Vascular medicine (London, England), 10(4), 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1191/1358863x05vm639ra

- Sevy JO, Sina RE, Varacallo M. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Oct 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448179

- Morell P, Quarles RH. The Myelin Sheath. In: Siegel GJ, Agranoff BW, Albers RW, et al., editors. Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. 6th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK27954/

- Tamai, K., Terai, H., Iwamae, M., Kato, M., Toyoda, H., Suzuki, A., Takahashi, S., Sawada, Y., Okamura, Y., Kobayashi, Y., Nakamura, H. (2024). Residual Paresthesia After Surgery for Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: Incidence and Impact on Clinical Outcomes and Satisfaction. Spine, 49(6):p 378-384, DOI: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000004907

- Milligan, J., Ryan, K., Fehlings, M., & Bauman, C. (2019). Degenerative cervical myelopathy: Diagnosis and management in primary care. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien, 65(9), 619–624.

- Miller, R. H., Fyffe-Maricich, S., & Caprariello, A. C. (2017). Animal models for the study of multiple sclerosis. Animal Models for the Study of Human Disease, 967–988. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-809468-6.00037-1

You must be logged in to post a comment.