February

14

February

14

Tags

Your Love Is My Drug

“Maybe just need some rehab, or maybe just need some sleep…” Kesha wasn’t wrong in comparing love to a drug. No matter what you define as a drug, intense romantic love has intoxicating effects. Studies have shown that the brain responds to love through mechanisms similar to those of addictive substances1,2. Whether it’s the rush of infatuation or the sting of heartbreak, each phase of love is underpinned by neural circuits that fuel our most intense cravings. To celebrate Valentine’s Day, let’s explore how this potent cocktail of desire, reward, and memory can leave trails of rose petals in our brains.

To study romantic love, researchers recruit people who claim to be head over heels in love. Once in the lab, these lovebirds undergo functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to track activity across the brain in real-time. Unlike structural MRI scans which provide information about the “structure” of the brain, fMRI scans provide information about the “function” of the brain by recording which brain regions light up while people are completing tasks. In love studies, participants typically view photos of their beloved, family members, and strangers, allowing scientists to map the neural signatures of romantic love versus other types of connections (or lack thereof). These studies reveal how love travels through the brain, offering insight into why we fall for certain people and how a fleeting spark can set off a burning love.

Finding your vice

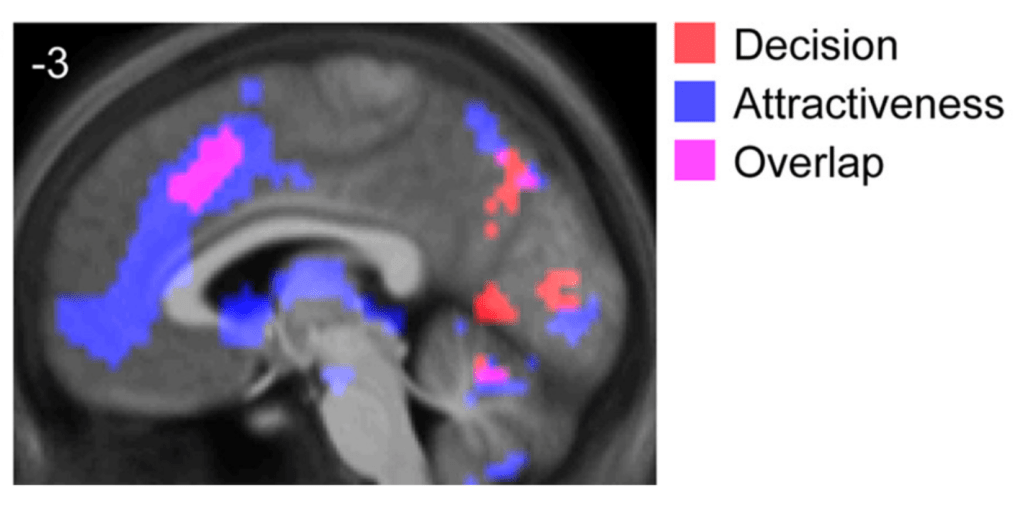

When it comes to choosing partners, there’s more than one theory at play. We’ve all heard that opposites attract, but the ‘similarity-attraction hypothesis’ is a long-standing and widely accepted theory that we choose our closest relationships (platonic and romantic) based on how similar they are to ourselves3. But what about the captivating feeling when a single glance sparks an instant connection? The phenomenon of love at first sight is thought to be housed in the part of the brain known as the frontal cortex, where some of our most important cognitive and emotional functions are controlled. Brain imaging studies have revealed the exact brain regions that choose who we pursue and reject. When evaluating a potential partner, the paracingulate cortex (the hall monitor of emotions and social interactions) considers physical beauty while the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (the guru of self-awareness) brings up your preferences based on perceived personality4 as seen in Figure 1. By mapping these neural processes, researchers have shown that our romantic decisions are anything but random. The brain seamlessly blends immediate visual appeal with deeper personality assessments, ensuring that both instant chemistry and lasting compatibility inform how we shape our close relationships.

(Cooper et al., 2012)

Getting hooked

Once the initial attraction takes hold, the brain becomes even more engaged in the process of bonding. The brain craves pleasure so much that it naturally creates and releases opioids, which enhance feelings of enjoyment. Endogenous opioid release has been linked to enjoying a delicious meal5 and laughing with friends6. It’s no surprise, then, that the brain opioid theory of social attachment suggests that endogenous opioid release is necessary to maintain social bonds7. Although direct connections to romantic love are still being explored, the natural release of opioids is especially relevant in the context of social touch8, which plays a key role in romantic interactions. A similar neurochemical process also underlies the post-workout rush of endorphins during a runner’s high9—just like the excitement you feel when brushing hands with your crush for the first time.

Symptoms of substance addiction often accompany the early phases of a new relationship. From euphoria when you’re with that special someone to developing emotional and physical dependence, these experiences are indicative of the brain’s activated reward system. As attachment grows, a loved one becomes a source of comfort, making separation feel like a form of withdrawal. Neuroimaging studies during the early stages of romantic love2 show that falling in love triggers the same brain circuits tied to motivation, compulsive behavior, and cravings seen in addictive disorders. Fixation on a partner resembles compulsive drug-seeking behavior while the escalating desire for their presence mirrors the development of tolerance. So what drives love’s addictive pull? The answer lies deep in the brain’s reward circuitry where an intricate dance of neurochemicals keeps us hooked on love.

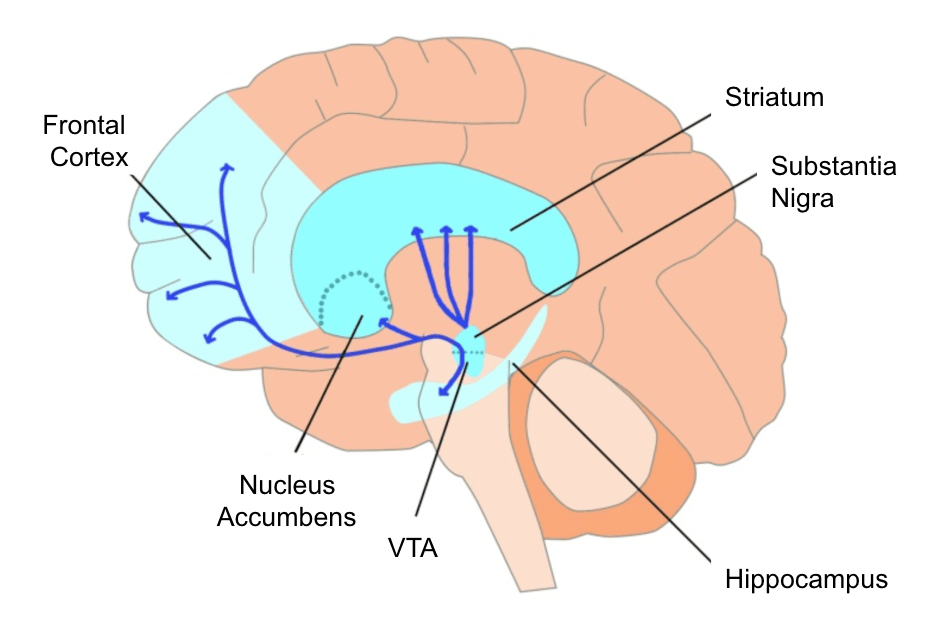

Love involves many brain regions, but a key player is the ventral tegmental area (VTA) where oxytocin and dopamine create all those warm and fuzzy feelings10 that keep us coming back for more. The VTA is typically responsible for motivation, reinforcement learning, and responses to pleasurable experiences like food and social interactions. The neurons in this region then tell their friends (other neurons) in different areas (see Figure 2) like the striatum (the habit-forming hub), nucleus accumbens (the pleasure center), and hippocampus (the memory organizer) all about this lovin’ feeling. The caudate region within the striatum (associated with goal-directed behavior and learning) is highly activated in the early stages of romantic love, but this activity tends to diminish as the relationship progresses2. As relationships mature, regions within the substantia nigra and cortex that are more involved in care and attachment are activated alongside the VTA11,12, similar to activation seen when studying maternal love. Although the initial intensity may fade, many enduring relationships experience a rekindling of neural activity in those reward circuits, reflecting a sustained and evolving form of love.

The dark side of desire: more than a gut feeling

Unfortunately, all good things must come to an end. Whether it’s rejection or a messy breakup, the feelings of heartbreak can be just as intense as the feeling of falling in love. In a heartbroken brain, the VTA still exhibits heightened activity as reward-expecting neurons prolong their activity, yearning for the lost connection13. Neural circuits within the dopaminergic reward system that respond to both gains and losses are also activated. Interestingly, this activity is strikingly similar to the reaction to a major gambling loss. Viewing photos of the person who rejected them stimulates activity in areas associated with drug cravings, fueling those obsessive thoughts about an ex. But heartbreak isn’t just in our heads, it’s deeply connected to the rest of the body.

The gut-microbiota-brain axis describes the complex relationship between the microorganisms living in your gastrointestinal tract and their influence on the brain. A healthy gut microbiota is characterized by a stable and diverse community of microorganisms, which has been linked to better immunity, infection resistance, and reduced inflammation. In contrast, reduced diversity in the gut microbiota has been associated with conditions like obesity, cardiac disease, type 2 diabetes, and inflammatory disorders14. Couples often share similar microbiota profiles from kissing, sharing meals, and even direct skin contact–and this is especially true for couples that live together. When you’re in a happy romantic relationship, your gut microbiota is pretty diverse, but when stress and/or sadness kick in, like after a breakup, that diversity tends to drop. Heartbreak doesn’t just mess with your mental health, but it may also have consequences on your physical health.

Ultimately, love is a rollercoaster of intense highs and lows that leave their mark on the brain. Following similar neural pathways as addiction, love could be considered a potent substance, one that shapes our behaviors and emotions. But love’s addictive pull doesn’t have to be a negative force, it has the potential to be a positive addiction and may inform new methods for treating substance use disorders. Scientists have proposed using romantic love as a reward replacement for addictive substances, offering a healthier alternative that provides similar emotional rewards. Love can be just as powerful as any drug, with great potential to heal and transform, offering a more fulfilling and lasting kind of addiction. ❤

References

- Fisher, H. E., Xu, X., Aron, A., & Brown, L. L. (2016). Intense, Passionate, Romantic Love: A Natural Addiction? How the Fields That Investigate Romance and Substance Abuse Can Inform Each Other. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00687

- Yang, Y., Wang, C., Shi, J., & Zou, Z. (2024). Joyful growth vs. compulsive hedonism: A meta-analysis of brain activation on romantic love and addictive disorders. Neuropsychologia, 204, 109003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2024.109003

- Barelds, D. P. H., & Barelds-Dijkstra, P. (2007). Love at first sight or friends first? Ties among partner personality trait similarity, relationship onset, relationship quality, and love. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24(4), 479–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407507079235

- Cooper, J. C., Dunne, S., Furey, T., & O’Doherty, J. P. (2012). Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortex Mediates Rapid Evaluations Predicting the Outcome of Romantic Interactions. The Journal of Neuroscience, 32(45), 15647–15656. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2558-12.2012

- Tuulari, J. J., Tuominen, L., Boer, F. E. de, Hirvonen, J., Helin, S., Nuutila, P., & Nummenmaa, L. (2017). Feeding Releases Endogenous Opioids in Humans. Journal of Neuroscience, 37(34), 8284–8291. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0976-17.2017

- Manninen, S., Tuominen, L., Dunbar, R. I., Karjalainen, T., Hirvonen, J., Arponen, E., Hari, R., Jääskeläinen, I. P., Sams, M., & Nummenmaa, L. (2017). Social Laughter Triggers Endogenous Opioid Release in Humans. The Journal of Neuroscience, 37(25), 6125–6131. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0688-16.2017

- Inagaki, T. K., Ray, L. A., Irwin, M. R., Way, B. M., & Eisenberger, N. I. (2016). Opioids and social bonding: Naltrexone reduces feelings of social connection. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(5), 728–735. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsw006

- Nummenmaa, L., Tuominen, L., Dunbar, R., Hirvonen, J., Manninen, S., Arponen, E., Machin, A., Hari, R., Jääskeläinen, I. P., & Sams, M. (2016). Social touch modulates endogenous μ-opioid system activity in humans. NeuroImage, 138, 242–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.05.063

- Mosko, J. (2024). Chasing a runner’s high. Neuwrite San Diego. https://neuwritesd.org/2024/01/25/chasing-a-runners-high

- Aron, A., Fisher, H., Mashek, D. J., Strong, G., Li, H., & Brown, L. L. (2005). Reward, Motivation, and Emotion Systems Associated With Early-Stage Intense Romantic Love. Journal of Neurophysiology, 94(1), 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00838.2004

- Shih, H.-C., Kuo, M.-E., Wu, C. W., Chao, Y.-P., Huang, H.-W., & Huang, C.-M. (2022). The Neurobiological Basis of Love: A Meta-Analysis of Human Functional Neuroimaging Studies of Maternal and Passionate Love. Brain Sciences, 12(7), 830. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12070830

- Acevedo, B. P., Aron, A., Fisher, H. E., & Brown, L. L. (2011). Neural correlates of long-term intense romantic love. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(2), 145. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsq092

- Fisher, H. E., Brown, L. L., Aron, A., Strong, G., & Mashek, D. (2010). Reward, Addiction, and Emotion Regulation Systems Associated With Rejection in Love. Journal of Neurophysiology, 104(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00784.2009

- Chuang, J.-Y. (2021). Romantic Relationship Dissolution, Microbiota, and Fibers. Frontiers in Nutrition, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.655038

- Dunne, T. (2017). Not just a four-letter word: The role of neuroendocrine factors in romantic love. British Association of Psychology. https://www.bap.org.uk/articles/not-just-a-four-letter-word/

You must be logged in to post a comment.