May

15

May

15

Tags

Making a mom: hormones and maternal behavior

It was Mother’s Day this weekend… have you called your mom yet?

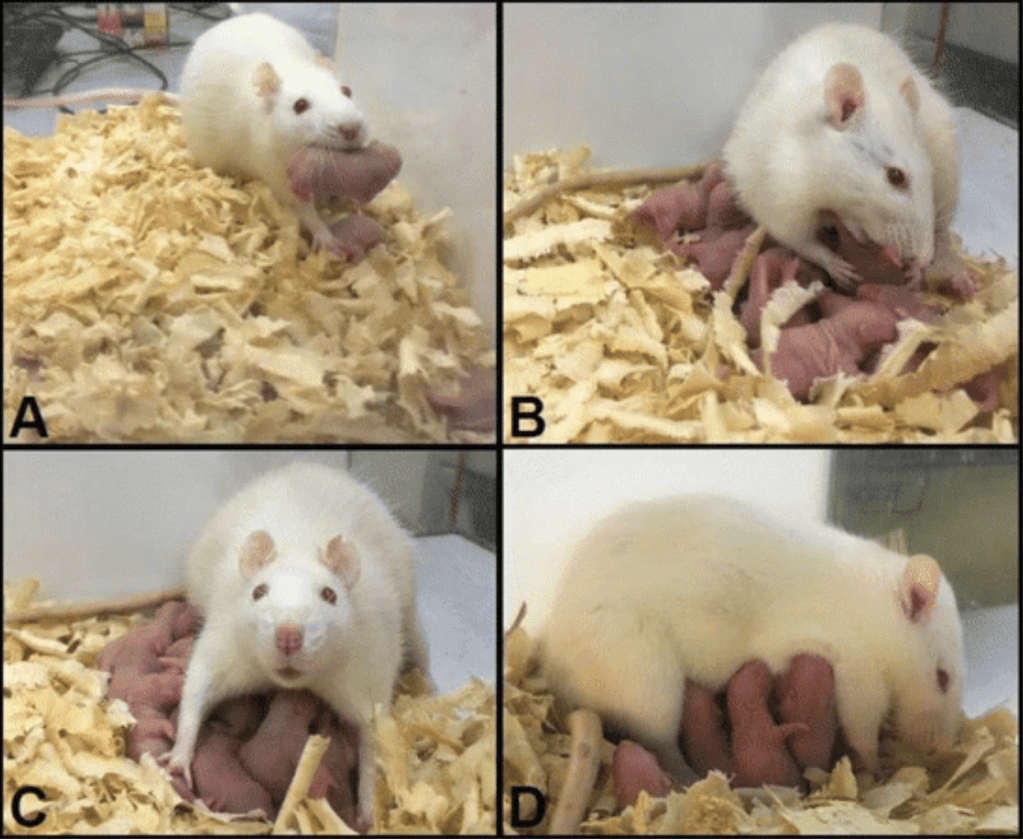

Maternal bonds are essential for the survival of the infant, as well as to encourage the mother to make sacrifices and engage in parental behaviors to care for her young. This is something that your mom probably felt as soon as she met you… or maybe even earlier (Bridges, 2015). This is not unique to humans, and is present in many species across the animal kingdom. In rodents, expectant mothers exhibit heightened levels of nest building and intruder aggression. A motivation to engage in positive maternal behaviors also occurs immediately following parturition, including pup retrieval, grooming, and nursing. For example, new rat mothers will press a lever over 100 times in one hour to have pups delivered to her nest, while virgin females will display maternal behaviors towards adopted young after as few as five days (Rilling & Young, 2014). How does this happen? What are the underlying mechanisms behind why mothers will engage in maternal behaviors and make sacrifices to protect their young?

Getting hormonal: estradiol and progesterone

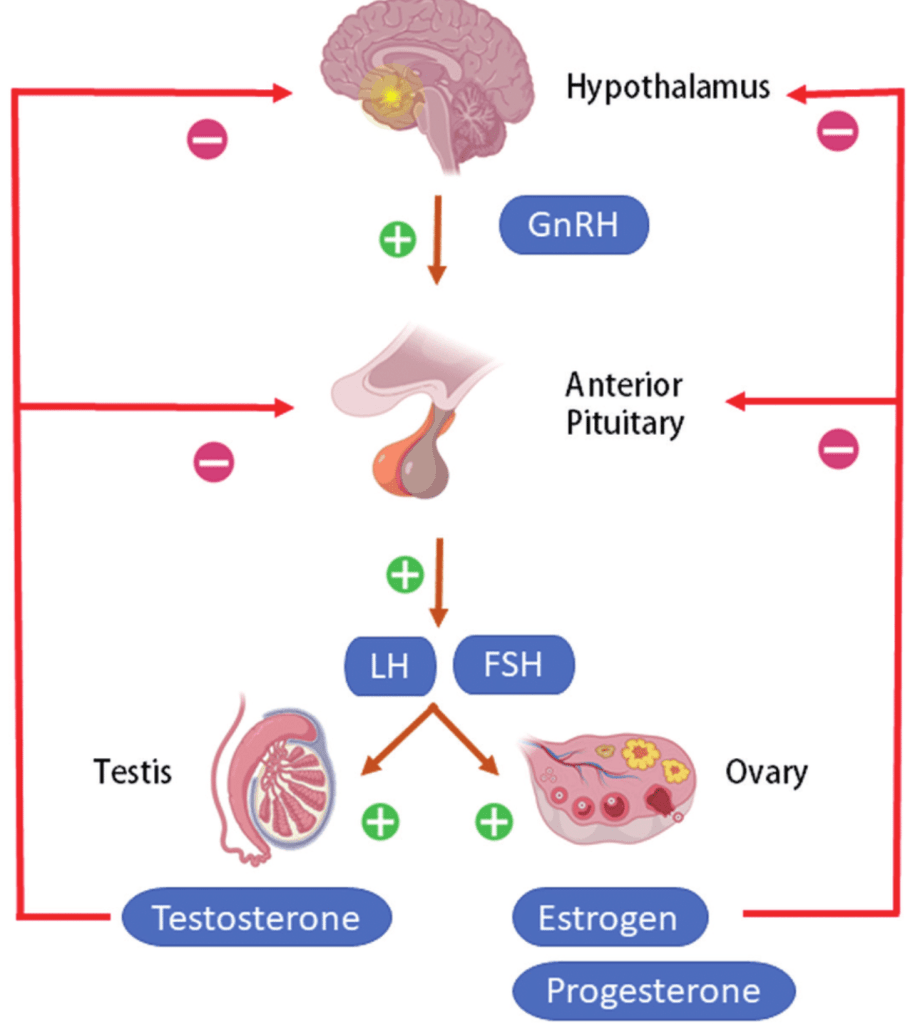

While there are many mechanisms which each lend a helping hand in preparing your mom to care for you, one key player is the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad (HPG) axis. Fertility and pregnancy are reliant upon the neural and endocrine activity within this circuit, which regulates the secretion of sex steroid hormones by the gonads. This includes estrogens and progestins, which are thought to play a role in the onset of maternal behavior (Saltzman & Meastripieri, 2011). Levels of circulating progesterone and estradiol, the most potent and prevalent member of the estrogen family in females, fluctuate dramatically during pregnancy. Estrogens and progestins are elevated throughout much of primate pregnancy, with the former remaining high throughout the second half of gestation while the latter drops prior to parturition. This pattern is thought to play a role in the onset of maternal behaviors during the later stages of pregnancy. Levels of circulating estradiol correlate with the number of interactions between stranger infants and female pigtail macaques during their last trimester, while the administration of estradiol to ovariectomized rhesus macaques, meaning their ovaries were removed, increases their infant-handling. Furthermore, it may also influence the motivation to engage in maternal behaviors following your birth. Virgin ovariectomized marmosets given treatments modeled after the endocrine milieu of late pregnancy engage in increased bar-pressing to terminate vocalizations of infant distress and view model young. Furthermore, red-bellied tamarin mothers who exhibited consistently elevated levels of urinary estradiol at the end of pregnancy were significantly more likely to engage in maternal behaviors following parturition and have infants survive beyond one week. This suggests that, from before you were even born and after you met, endogenous fluctuations of estrogens and progestins were preparing your mom to care for you.

Your mom’s hard work taking care of you may make you a better parent

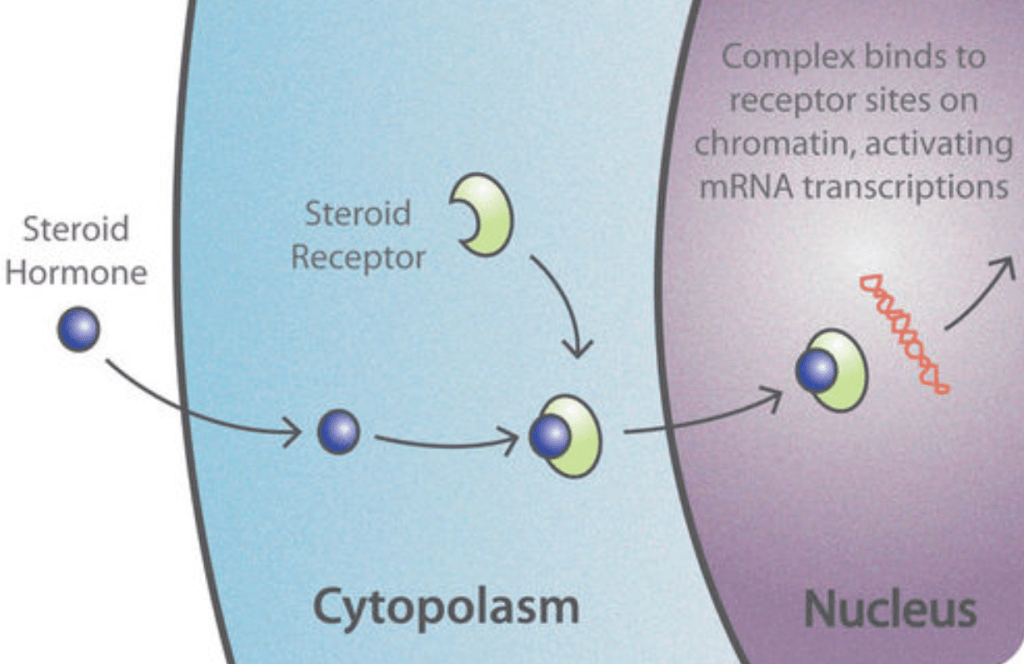

Steroid hormones, such as estradiol, are lipophilic, meaning they can dissolve in lipids or fats. This allows them to cross the cell membrane and act on intracellular receptors which act as nuclear transcription factors, in addition to their ability to bind to transmembrane receptors (Tuohimaa et al., 1996). Nuclear transcription factors can mediate gene expression and the transcription of DNA into mRNA by targeting specific enhancer regions known as steroid response elements. These short DNA sequences enhance the transcription of nearby genes.

In particular, much research into the effects of estradiol on maternal behavior have been conducted on the transcription factor ERɑ (ESR1). Mouse mothers who engage in high rates of grooming and pup licking express elevated levels of ESR1 expression in the medial preoptic area (MPOA) of the hypothalamus, a key region involved in the stimulation of maternal care (Bridges et al., 2015; Champagne et al., 2006). Furthermore, this is passed down to their offspring, both biological and adopted, who exhibit similar patterns of ESR1 MPOA expression and demonstrate a greater engagement in maternal behaviors towards their own pups. But how does this happen? In humans, the ER gene is transcribed by two promoters, or DNA sequences that initiate the transcription of downstream genes and can be bound to by transcription factors. Promoter A has no known functional murine counterpart. On the other hand, the human B promoter is more than 70% homologous to the rat ER promoter, as observed following sequencing of the gene’s exon 1b region. Exons can be defined as coding regions of DNA. They are preserved in mature mRNA following transcription and contain important information about the amino acid sequence of the protein, playing an important role when it is translated by ribosomes. Elements within exon 1b are therefore thought to potentially play a role in the transcriptional regulation of ESR1, and have a subsequent downstream effect on maternal behavior. CpG sites, sequences of DNA containing a cytosine followed by a guanine nucleotide, can be modified via a process associated with decreased gene expression known as DNA methylation, in which a methyl group is added to the cytosine base. Mothers who engage in greater rates of maternal behavior demonstrate significantly lower levels of methylation in ESR1 promoters, especially within the MPOA.

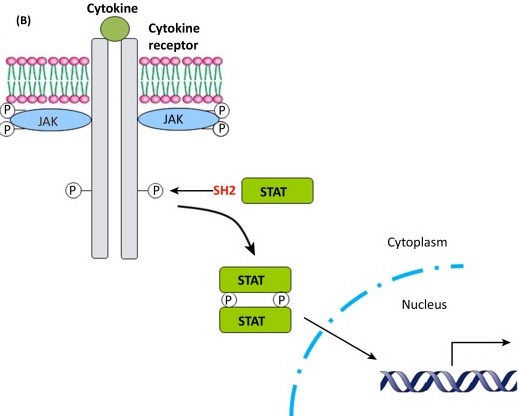

Furthermore, one such differentially methylated CpG site, site 3, was located within a consensus Stat5b binding site. Stat5b is a member of the Janus kinase (JAK)-Stat5b pathway, in which a ligand binds to a cell surface receptor, triggering the activation of its associated kinase, which in turn activates Stat5b. It then goes on to act as a transcription factor, translocating to the nucleus and binding to the promoter region of the ER gene to regulate transcription. Despite similar levels of overall MPOA Stat5b expression, mothers who engage in increased maternal behaviors, as well as their offspring, exhibit increased regional levels of Stat5b ESR1 promoter 1b binding. This suggests a correlation between an offspring’s exposure to maternal behaviors and methylation of the Stat5 consensus sequence, causing an increase in Stat5 ESR1 1b promoter binding. This would in turn lead to an increase in ESR1 MPOA expression that could promote an increase in their own maternal behaviors as adults. In addition to manipulating the genomic action of estradiol, Stat5’s modulation of ESR1 expression means this maternal phenomenon can also indirectly affect another endocrine regulator of maternal behavior: oxytocin.

Let’s talk oxytocin

Research has suggested that ESR1 can regulate oxytocin receptor (OT) binding in the mouse MPOA, as well as stimulate the transcription of oxytocin receptors in ewes (Champagne et al., 2006; Fleming et al., 2006). This mechanism has also been applied to studies on maternal behavior. Oxytocin is required for maternal care and differences in receptor expression are correlated to variations in rates of maternal behavior. For example, inhibiting oxytocin activity reduces rates of maternal behaviors, and mouse mothers who more greatly engage in them demonstrate significantly higher levels of OT binding in the MPOA. These differences are abolished following ovariectomy and reinstated with estrogen administration. The role of ESR1 in mediating MPOA OT binding suggests that it could share a pattern of cross-generational transmission similar to that seen in estradiol. Specifically, that the biological and adopted offspring of mothers who engage in greater rates of maternal behaviors will subsequently display a similar parenting style as adults, as well as increased MPOA OT binding.

Unlike estradiol and progesterone, whose lipophilic identities allow them to directly act on intracellular receptors, oxytocin is hydrophilic, meaning it dissolves in water and cannot readily cross the cell membrane. The hormone is synthesized within the central nervous system, particularly the paraventricular (PVN) and supraoptic (SON) nuclei of the hypothalamus (Saltzman & Maestripieri, 2011). Oxytocin can then be segregated into two separate systems with little co-influence due to the hormone’s difficulty in crossing the blood-brain barrier. Oxytocin can play a key role in peripheral tissues outside the brain after being released into circulation by hypothalamic neurons which project to the posterior pituitary. It is released during uterine contractions and suckling to play key roles in maternal physiological functions such as myometrial contractions and milk letdown. In contrast, intracerebral oxytocin is released via PVN neurons, where it is involved in sexual behavior, social bonding, stress response, and the expression of maternal behavior. For example, tyrosine-hydroxylase neurons in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus are found in greater numbers in females than males, and are also increased postpartum (Scott et al., 2015). They form connections with oxytocinergic PVN neurons, facilitating the release of oxytocin and a subsequent increase in parental behaviors, such as pup retrieval and maternal aggression, in both multiparous and virgin adopting mothers. Furthermore, in both the brain and periphery, the expression of oxytocin and its receptor are upregulated following surges of estradiol and decreased levels of progesterone, such as during the later stages of pregnancy (Saltzman & Maestripieri, 2011). This suggests that the hormone may also help prepare your mom to take care of you. Oxytocin can reduce lamb rejection and plays a role in developing mother-infant bonds in parturient ewes, and it similarly facilitates a transition from pup aversion to attraction in new rat mothers. While in human mothers and fathers, affectionate contact with their babies is positively correlated with concentrations of circulating oxytocin (Rilling & Young, 2014).

Putting together what makes your mom special

Maternal behaviors manifest thanks to a constellation of complex mechanisms and a myriad of circuits all coming together to help prepare your mom to care for you. Many additional brain regions, hormones, and circuits that weren’t discussed here are also involved in other aspects of maternal bonding. For example, projections from the hypothalamus to the periaqueductal gray play a role in why mothers find their children attractive regardless of whether you were an ugly baby, while the dopamine reward system helps maintain your bond and her drive to engage in maternal behaviors long after birth (Bridges, 2015). Even so, we’ve only scratched the surface when it comes to understanding how this all works. Your mom has gone through a lot to take care of you, so make sure to wish her a happy Mother’s Day if you haven’t already.

References

Bridges, R. S. (2015). Neuroendocrine regulation of maternal behavior. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 36: 178-196.

Benedetto, L., Torterolo, P., & Ferreira, A. (2018). Melanin-concentrating hormone: role in nursing and sleep in mother rats. Melanin-Concentrating Hormone and Sleep: 149-170.

Boundless (2013). Anatomy & Physiology. Pressbooks. Chapter 88, Hormones.

Champagne, F. A., Weaver, I. C., Diorio, J., Dymov, S., Szyf, M., & Meaney, M. J. (2006). Maternal care associated with methylation of the estrogen receptor-alpha1b promoter and estrogen receptor-alpha expression in the medial preoptic area of female offspring. Endocrinology, 147(6): 2909-2915.

De Marco, A., Cinque, C., Sanna, A., Zuena, A. R., Giuliani, A., Thierry, B., & Cozzolino, R. (2024). Maternal style and offspring behavior in Macaca tonkeana. International Journal of Primatology, 46: 321-342.

Durham, G. A., Williams, J. J., Nasim, M. T., & Palmer, T. M. (2019). Targeting SOCS proteins to control JAK-STAT signalling in disease. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 40(5): 298-308.

Fleming, J. G., Spencer, T. E., Safe, S. H., & Bazer, F. W. (2006). Estrogen regulates transcription of the ovine oxytocin receptor gene through GC-rich SP1 promoter elements. Endocrinology, 147(2): 899-911.

Gupta, P., Mahapatra, A., Suman, A., & Singh, R. K. (2021). Hot topics in Endocrinology and Metabolism. Anthem (AZ): IntechOpen. Chapter 2, Effect of endocrine disrupting chemicals on HPG axis: a reproductive endocrine homeostasis.

Rilling, J. K., & Young, L. J. (2014). The biology of mammalian parenting and its effect on offspring social development. Science, 345(6198): 771-776.

Saltzman, W., & Maestripieri, D. (2011). The neuroendocrinology of primate maternal behavior. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 35(5): 1192-1204.

Scott, N., Prigge, M., Yizhar, O., & Kimchi, T. (2015). A sexually dimorphic hypothalamic circuit controls maternal care and oxytocin secretion. Nature, 525: 519-522.

Tuohimaa, P., Bläuer, M., Pasanen, S., Passinen, S., Pekki, A., Punnonen, R., Syvälä, H., Valkila, J., Wallén, M., Väliaho, J., Zhuang, Y. H., & Ylikomi, T. (1996). Mechanisms of action of sex steroid hormones: basic concepts and clinical correlations. Maturitas, 23: S3-S12.

You must be logged in to post a comment.