October

12

October

12

Tags

Ten Years in the Making

10 years ago, I was in a medically induced coma. On life support, my life rested in the hands of the incredible staff at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego (RCHSD). On October 8th, 2013, I suffered a severe traumatic brain injury due to a suicide attempt: I had jumped 3 stories from the parking garage at Parkway Plaza Mall here in San Diego. In previous articles, I have mentioned aspects of my injury and the epilepsy that resulted from it as it related to the topics of the articles. In this article, however, I will be centering the discussion of severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) around some of the ways in which it has affected me. Welcome to my life.

Severe TBI

Of the 16 diagnoses I had upon admission to the emergency department at RCHSD, the most significant was a diffuse axonal injury (DAI). A DAI is a type of severe TBI that results from a process known as shearing in the brain. Shearing occurs when the two hemispheres of the brain shift contralaterally–moving in opposite directions along the mid-section of the brain, known as the corpus callosum. As its Latin name, Callous Body, implies, the corpus callosum is a thick structure connecting the two hemispheres; it is comprised of the axons of many, many neurons, which make communication between the hemispheres possible. Shearing breaks up these axons, injuring the neurons connecting the hemispheres and resulting in widespread damage within the brain.

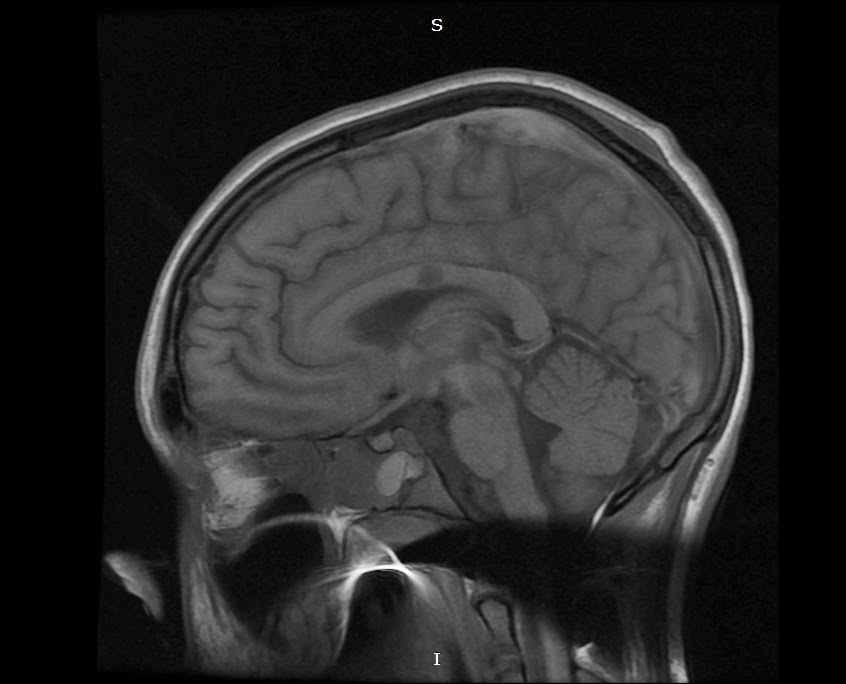

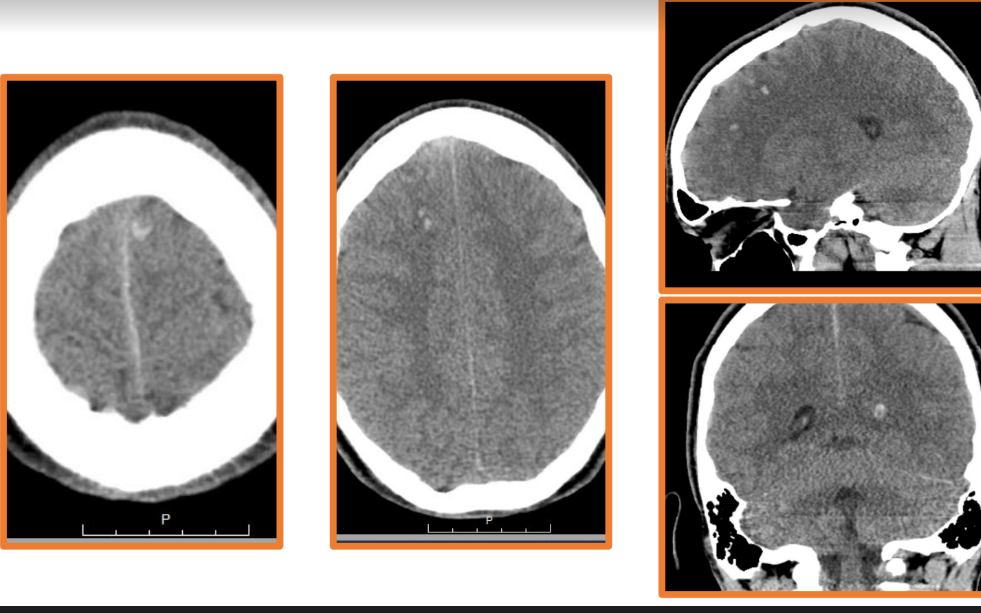

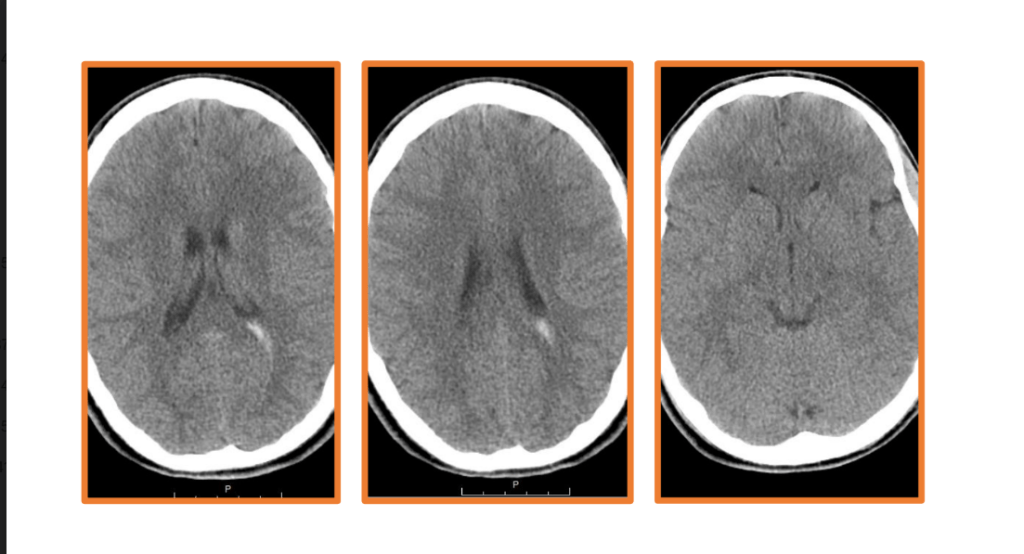

Here I have some CT and MRI images taken soon after my injury. The blurred parts of the MRI image towards the center show evidence of shearing. In addition, the bright white portions of the CT images represent accumulations of blood, known as hemorrhages. These also contributed to the extent of my injury. Had the emergency staff not implanted what is known as an intracranial pressure cup (ICP) to relieve the pressure from the excess fluid within my cranial cavity, my brain would have been displaced and squished down by the fluid, and the extent of my injury would have been much worse, potentially even fatal.

Spasticity

Sustaining a severe TBI has many consequences, which include physical disabilities, difficulties with sensory processing, cognitive impairments, and behavioral disorders. A common physical limitation that occurs after DAI is known as spasticity, or an abnormal increase in muscle tone and stiffness, which results in rigid movements and can cause issues with ambulation (walking), speech, and swallowing, and may have some discomfort/pain involved. In an individual with spasticity, their muscles remain contracted and stiff, and resist being stretched (2). Spasticity is caused by damage to neural pathways responsible for muscle movement and coordination.

Treatments for spasticity range from therapy to muscle relaxant medications, such as Baclofen. Baclofen is prescribed orally for patients with spasticity, but to get desirable effects in some people, higher doses must be used sometimes. However, higher doses of baclofen taken orally usually have side effects such as feeling sleepy, tired, dizzy or weak, feeling nauseous, headaches, blurred vision, and problems sleeping (3). For those who require higher doses to treat their spasticity, an alternative delivery method is available, which is to use a surgically implanted pump to continuously supply the spinal cord with Baclofen, allowing for the use of higher doses without side effects. Known as an intrathecal baclofen pump, this device is a round implant about the size of a hockey puck used to store about 6 months’ worth of medication, and it delivers it to the spinal cord intrathecally–in the cerebrospinal fluid that fills the space between the spinal cord and the tissue that surrounds it–via a catheter. Baclofen relaxes the constant contraction of the muscles, so this method of treatment helps restore fluidity in the individual’s movements and eases the tone in their muscles. However, not everyone can go through with this surgery (such as myself). Actually, I had a surgical injection of Baclofen a few weeks ago (09/26/2023) to test if it would work for me before going through with the implantation of the device. Results: it helped somewhat, but the side effects of the surgery itself (lumbar puncture) were severe enough that I’d rather not go through that again. I’ve gone 10 years without it, and all the while graduated from high school with honors and UCSD with a bachelor’s degree in Cognitive Science, I think I can function perfectly okay without it.

Recently, however, advancement in the treatment of spasticity has used Botox injections in regions affected. Because botox relaxes muscles, it helps relieve the stiffness caused by the constant contracture to aid in movement. This is why Botox is used by people who want to look younger, by relaxing the muscles, you are reducing wrinkling of the skin (when I told one of my teachers in high school I was going to have Botox injections in my legs, he joked around and said I’m going to make my legs look younger).The effects of botox injections used to treat spasticity last about three months (at least from my personal experience).

Cognition and Behavior

A patient’s cognitive abilities and behavior following a brain injury are something taken into account when physicians go to assess a patient’s likelihood and degree of recovery (prognosis). Many different effects on cognition and behavior can occur, and one behavioral side effect from severe TBI is known as neuroagitation, which, as I will mention, can actually give us insight into the mental state and recovery of a patient.

Neuroagitation refers to disorders of consciousness caused by severe traumatic brain injuries usually early on following their injury, shortly after emerging from a coma (cite). These disorders of consciousness, oddly enough, are usually good signs. They represent one of the first signs of returning of consciousness in a comatose patient. Research has evaluated the link between neuroagitation and the recovery of consciousness following severe TBI, as these behaviors represent goal-directed behaviors, rather than the non-purposeful movements sometimes encountered in patients in comatose states.

Now, here is a funny story that I tell all the time, and though it’s a story I tell just as something funny, it does have value and actually meant a lot about my state of mind at the time. As I said earlier, I was in a medically induced coma around this time last year, when I was in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) at RCHSD, for about a month. They had started weaning me off of the sedative medications that kept me in this coma, and one day what would be my future rehabilitation doctor came in to assess my eligibility for the severe TBI rehabilitation program. He gave a dire prognosis: that I would never be able to speak or move again. What he did not know, however, was that I was hearing every word he said, because I was completely aware. As my mom told me, I began to cry (my long-term memory formation was not engaged yet at this point, so I don’t remember this).

The next time the doctor came in to do rounds (Can you look at me? Can you lift your arm? Can you lift your leg?), I completely ignored him. After seeing this, and after the doctor left, my mom rushed to me, “Donovan, were you mad at him?” At the time, I could not speak. However, we had devised a system for me to communicate: for yes, I would raise my left arm, and for no, I would raise my left leg (I could only move the left side of my body at this point). So, I raised my left arm in response “Donovan, that’s the head of rehab! You have to show him what you can do!”

After pleading with the doctor, my mom was able to get him to come back into the room and repeat the exam: “Can you look at me?” My eyes dart towards him. “Can you raise your arm?” My left arm flops up. “Can you lift your leg?” I briefly raise my left arm. Continuing, this time he asks me, “Now, can you hold up a finger for me?” to determine fine motor coordination. I think you can imagine what finger an angry teenager would hold up. Yes, I flipped off the head of rehab at RCHSD. The room erupted in laughter, including from the doctor who I had just flipped off.

Funny story aside, as discussed earlier, this meant much more than showing the angsty teenager that I was. By displaying an agitated response and a purposeful movement, it indicated my level of consciousness, or rather, that my consciousness was still there. That I was still there.

Time is Function

For traumatic brain injuries, a slogan is used to describe recovery prospects: “Time is Function”. This is to say that the sooner the brain-injured patient gets into recovery and rehabilitation, the greater their prospects for recovery of function are. This is because the brain’s natural healing process, known as neuroplasticity, is greatest early on in recovery. Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to respond to the environment and stimuli it receives, and “rewire” itself accordingly. In rehabilitation, continued recovery of function is possible by repetitive performance of exercises that promote the strengthening of the proper neural circuits. Therefore, the reverse is also true: the longer it takes for the patient to enter recovery and rehabilitation, the worse their prospects for recovery are.

Speaking of which, following brain injury, there is a general pattern of recovery that most brain-injured patients follow, timewise. The slogan time is function still applies here, but based on how long it has been since the injury, we can predict what we can expect for recovery progression. For the first 3 months following a brain injury, we see daily improvements in the patient’s condition. 3-6 months: weekly improvements. 6-12 months: monthly improvements. Then, greater than 12 months after injury, spontaneous improvements start to diminish. Once patients reach the 2-year mark post-injury, spontaneous recovery generally ceases. However, this does not mean the individual is stuck like they are at that point forever. What I mean by saying spontaneous recovery is that improvements due purely to the passing of time cease. Improvements can still be accomplished by going to therapy and strengthening the desired neural circuits by continual practice. This is because your brain’s neural plasticity never ceases: it’s how we do so many things in our day-to-day lives, even if you are not brain-injured. Learning, making new memories, making associations, and forming habits, all require a plastic brain.

Conclusion

Now, what I have covered in this article is only beginning to scratch the surface of the consequences of TBI, and it has only begun to scratch the surface of the story of my recovery. Not only is every brain injury unique, given the complex structure of the brain and the myriad of ways in which it can be injured but the severity of an injury can vary greatly determined by certain factors at the time of injury as well. The severity of an injury and these other factors also determine the consequences of the brain injury.

Although I have a jovial and cavalier attitude throughout this article, I would be remiss if I were not to underscore the importance of our awareness of the consequences of TBI, because TBI can and does affect so many people’s lives–tens of millions per year, actually. Not only does it leave many with lifelong disabilities, but a sizeable portion of those who suffer TBIs die because of it. In fact, approximately 70% of pediatric trauma-related deaths are from severe TBIs (cite; this article has many more statistics on TBI occurrences in the US). This being said, it is imperative that we spread more awareness of the consequences of TBI, and bolster prevention efforts. We owe it to our brains.

References

- Skalsky, A. (2023, March 14). Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Rehabilitation [PowerPoint slides]. Department of Orthopedics, University of California, San Diego. Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diffuse_axonal_injury

- https://www.aans.org/Patients/Neurosurgical-Conditions-and-Treatments/Spasticity

- https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/baclofen/side-effects-of-baclofen/

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsurg.2021.627008/full

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8710712/

You must be logged in to post a comment.