December

28

December

28

Tags

Into the Flow: Insights into the elusive Flow State

Have you ever been so absorbed in an activity that time stops; you are completely dialed in and acutely aware of every movement of your body; you’re performing at your highest level, but you feel no effort; you are completely in the moment, and it feels incredible! This is flow.

What is Flow?

I experienced something similar recently when I went to a dance class. The first half of the class was spent rehearsing a set of challenging moves. At first, my movements were disjointed and lacked fluidity, but after a bit of practice, towards the end, things just clicked into place. I stopped thinking about what came next, I felt like I had all the time in the world, the beat started, and I was in flow. “Fully in Sync,” “heightened state of awareness with no effort,” and “the highest form of concentration” are just some of the phrases that have been used to describe the flow state. In Olympic surfing, flow is even used as a judging criterion and is defined as the ability to get the most out of a wave from start to finish, with effortless motion, making an intense activity look seamless.

Originally coined by the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, flow is a mental state of optimal experience where individuals find themselves fully absorbed in an activity, often reaching a heightened sense of focus and productivity. Since then, researchers have strived to characterize and study flow, hoping to uncover the secrets of achieving this ultimate level of performance. Flow can be experienced in physical endeavors and in more cognitive tasks such as writing an essay or article, writing code to solve a problem, or even performing surgery. Being in flow has been characterized by a few salient features: the individual is completely absorbed and engaged in the task and is much less likely to become distracted by things like a text message or a loud sound. There is less focus on self-reflection and less worrying about how others may perceive your performance or what people think of you and your ability. Tasks are carried out almost automatically, with a smooth transition between conscious control and actions; imagine writing without any mental blocks, as if your thoughts are flying onto the paper. However, there is a component of feedback where one can monitor their performance while not necessarily being distracted by it, i.e., you can correct mistakes, but it doesn’t disrupt your thought process.

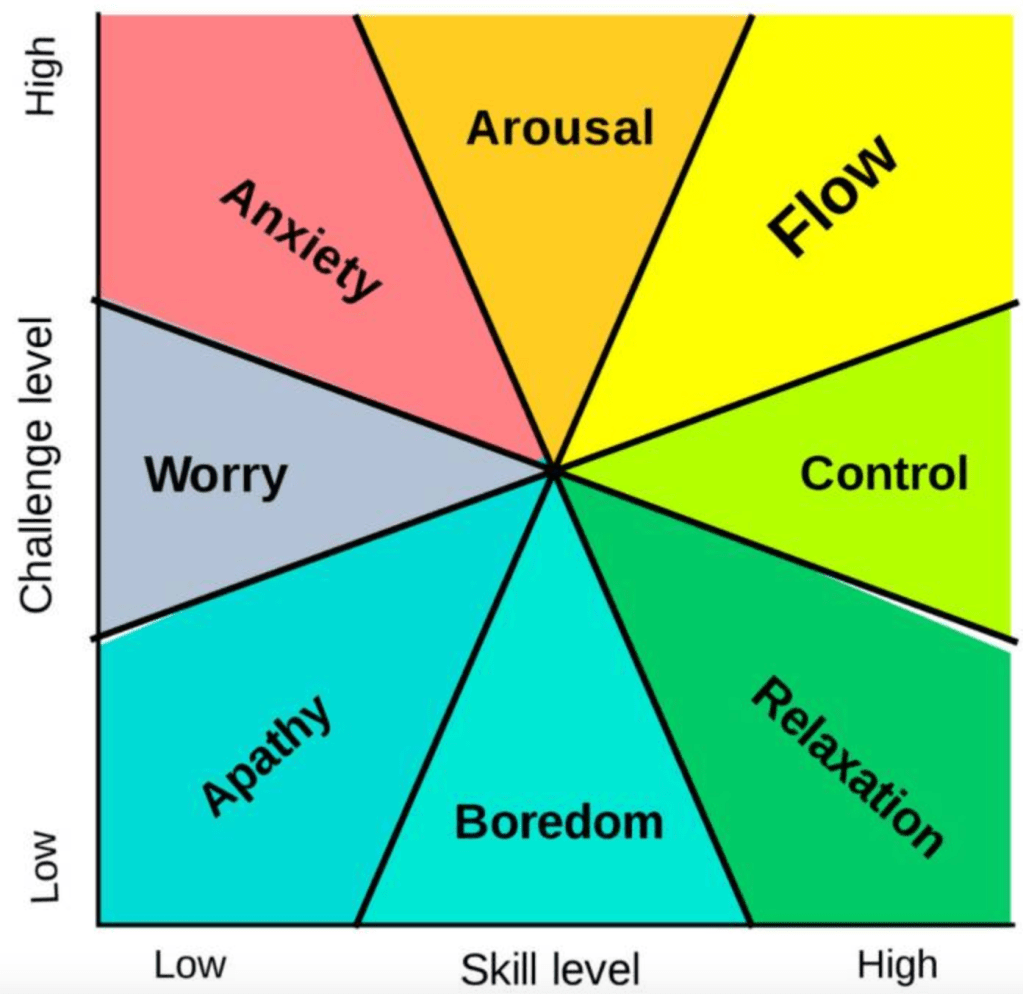

Notably, the type of task defines whether one can get into the flow state. Flow is mainly characterized by a perfect balance between skill and challenge (Fig. 1). Flow can only be achieved when the level of skills and challenge are both high. This means that the participant becomes bored if the task is too easy for their skill level. However, if the challenge is too high, it can result in stress and frustration. For example, in my dance class, I needed to learn the steps before I could experience the flow during execution. Similarly, it would be difficult to achieve flow when writing an article if one hadn’t researched beforehand and knew what they wanted to write. Thus, flow is also associated with an element of control where the individual feels that they are in control of what they’re doing; they have clear goals and know what must be done to achieve them. A common experience when in the flow is that feel-good feeling of being immersed in the task, which is the rewarding feeling that comes from seamless execution; think of athletes describing “runners high,” which typically happens a few miles into a run despite fatigue. Additionally, flow is also associated with an altered perception of time; time seems to slow down when in flow while simultaneously speeding up such that individuals often don’t realize how much time has gone by while they are in the flow.

The Brain in Flow

Given the automaticity of task performance in flow, the state has been associated with lower levels of conscious awareness during the task. Thus, researchers originally proposed that brain areas typically involved in executive function and cognitive ability, such as the cerebral cortex located in the front of the brain, were not involved in this state. Conversely, areas of the brain involved in task execution typically outside of the cortex were thought to play a significant role – the hypofrontal hypothesis. However, more recently, others have proposed that while this is true to some extent, it is actually the differential recruitment of brain attentional networks that enables flow. Through brain imaging studies, researchers have identified that when an individual is not engaged in a task, when their thoughts are drifting, or when they’re involved in self-reflective thoughts about the future or past, a particular set of cortical brain regions are activated. Together, these brain areas make up the default mode network (DMN). In contrast, a second network known as the central executive network (CEN) consists of a distinct set of cortical regions that are active when focused or deep in concentration and is essential for maintaining flow. Critically, the DMN and CEN tend to work in opposition to each other; when one is activated, the other is inactivated. A third network, the salience network (SN), is likely the key to mediating the switch between task-related (i.e., CEN-related) processing and non-task-related (i.e., DMN) processing (Fig. 2). The SN may mediate the switch in one of two ways, if the task is not challenging enough it may start to activate the DMN, and reduce the activation of the CEN, leading to more mind-wandering and reduced flow. Or, if the task is too challenging, it may cause the individual to make more errors, flow is reduced, and the individual increases their self-awareness, thus tipping the balance to reduced CEN activity compared to the DMN. Thus, several areas of the brain cooperate to enhance or disrupt flow.

Besides the activity of cortical networks in flow, chemical messengers in the brain, dopamine (DA), and norepinephrine (NE) are also proposed to play a role in producing flow. Researchers directly tested if areas involved in processing dopaminergic signals, the nucleus accumbens, were directly involved in the flow state. Participants were tested in an MRI brain scanner in three task conditions involving mental calculations. A boring version, where the task was too easy; an overload version, where the task was too challenging; and a flow version, which balanced both skill and challenges. Activity in the nucleus accumbens was highest, specifically in the flow condition, indicating that dopaminergic activity in that region may be prevalent during flow. Since this study focused only on performing mental calculations, it was unclear if the activity patterns existed in other kinds of tasks. However, the findings indicated that dopaminergic activity may be generally involved in the flow state. Moreover, increased dopamine explains some of the observations of individuals experiencing flow, such as reducing fatigue, relentless focus toward that task, increased motivation, and the rewarding experience of being in flow.

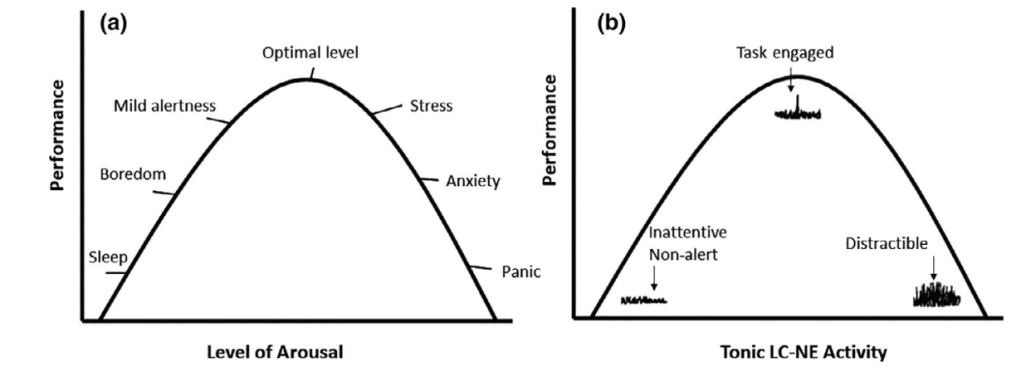

The strong task engagement associated with flow is linked to the brain’s norepinephrine system. Norepinephrine (more frequently known as adrenaline) influences arousal and stress in the brain and plays a key role in task engagement. Norepinephrine levels during task execution cycles between baseline or moderate levels to maintain arousal and increased levels in response to a reward or stimuli. If engaged in a task, the person experiences a good level of arousal and responds well to task-relevant information. However, if norepinephrine levels fall too low, arousal is lowered, the individual may become bored and subsequently feel disengaged from the task. Conversely, when norepinephrine is too high, it could signal high arousal, which in turn causes a sense of anxiety and responsiveness to distracting stimuli; also resulting in task disengagement (Fig. 3). Thus, an optimal level of norepinephrine is required to maintain flow.

Can We Achieve Flow?

While the neural mechanisms of the flow state are still being uncovered, insight into how humans achieve this coveted state may be gained from observations of athletes and high performers. When researchers interviewed athletes about their flow experience, they identified factors that helped or prevented flow. For example, if their performance felt good, it would contribute to flow; if it felt poor, it would disrupt the flow. While confidence and a positive attitude helped flow, doubt or putting pressure on oneself disrupted flow. Optimal planning and physical preparation ahead of time improved flow, while confusion or a lack of preparation disrupted flow. Thus, a combination of preparedness and emotional state before and during the task determines flow. So, while it may take practice and learning for us to leverage flow, in the meantime, if your training and task align, catch the wave and ride the flow.

References

- van der Linden D, Tops M, Bakker AB. Go with the flow: A neuroscientific view on being fully engaged. Eur J Neurosci. 2021; 53: 947–963. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.15014

- Ulrich M, Keller J, Hoenig K, Waller C, Grön G. Neural correlates of experimentally induced flow experiences. Neuroimage. 2014 Feb 1;86:194-202. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.019. Epub 2013 Aug 17. PMID: 23959200.

- Gold J, Ciorciari J. A Review on the Role of the Neuroscience of Flow States in the Modern World. Behav Sci (Basel). 2020 Sep 9;10(9):137. doi: 10.3390/bs10090137. PMID: 32916878; PMCID: PMC7551835.

- Clara Alameda, Daniel Sanabria, Luis F. Ciria,The brain in flow: A systematic review on the neural basis of the flow state,Cortex,Volume 154,2022,Pages 348-364,ISSN 0010-9452,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2022.06.005.

- Cheron G. How to Measure the Psychological “Flow”? A Neuroscience Perspective. Front Psychol. 2016 Dec 6;7:1823. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01823. PMID: 27999551; PMCID: PMC5138413.

- Harris DJ, Vine SJ, Wilson MR. Neurocognitive mechanisms of the flow state. Prog Brain Res. 2017;234:221-243. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2017.06.012. Epub 2017 Jul 24. PMID: 29031465.

- Susan A. Jackson (1995) Factors influencing the occurrence of flow state in elite athletes, Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 7:2, 138-166, DOI: 10.1080/10413209508406962

- Antonini Philippe R, Singer SM, Jaeger JEE, Biasutti M, Sinnett S. Achieving Flow: An Exploratory Investigation of Elite College Athletes and Musicians. Front Psychol. 2022 Mar 30;13:831508. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.831508. PMID: 35432058; PMCID: PMC9009586.

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience.” Journal of Leisure Research, 24(1), pp. 93–94

- https://www.surfertoday.com/surfing/speed-power-and-flow-the-competitive-surfing-formula

Pingback: Chasing a Runner’s High | NeuWrite San Diego