July

11

July

11

Tags

The World in 3D: A Glimpse Into Depth Perception

We see the world around us in three dimensions. These dimensions can be described as different planes in physical space, extending from any central point in not only vertical and horizontal directions, but also in depth. By using our vision to assess how near or far something is from us, and interpreting objects in three-dimensional space (that is to say, the X, Y, and Z axes illustrated in Figure 1) we are utilizing our skill of depth perception.

Depth perception, or the ability to appreciate and understand differences in depth, is also referred to as stereopsis [1]. Perceiving depth is crucial for performing coordinated and dexterous tasks, like swinging a baseball bat at just the right instant as a pitch comes hurtling towards you. However, it is also crucial for simpler tasks, like reaching for and picking up your coffee cup from your desk smoothly. Miscalculations of depth may result in a swing-and-a-miss in the big game, or in a spill as you stub your fingers into your coffee cup and knock it over.

How We See

Unlike 3D movie experiences, for which we require special glasses to perceive depth created on a flat screen, our naked eyes are remarkably good at detecting how near or far away an object is in the real world. Our eyes rely on external input as well as input from one another. Many animals, including humans, have two eyes that work together to help us perceive depth accurately. This is called binocular vision. The prefix ‘bi’ simply refers to our pair of eyes, and is juxtaposed by monocular vision, a type of eyesight wherein there is only one eye.

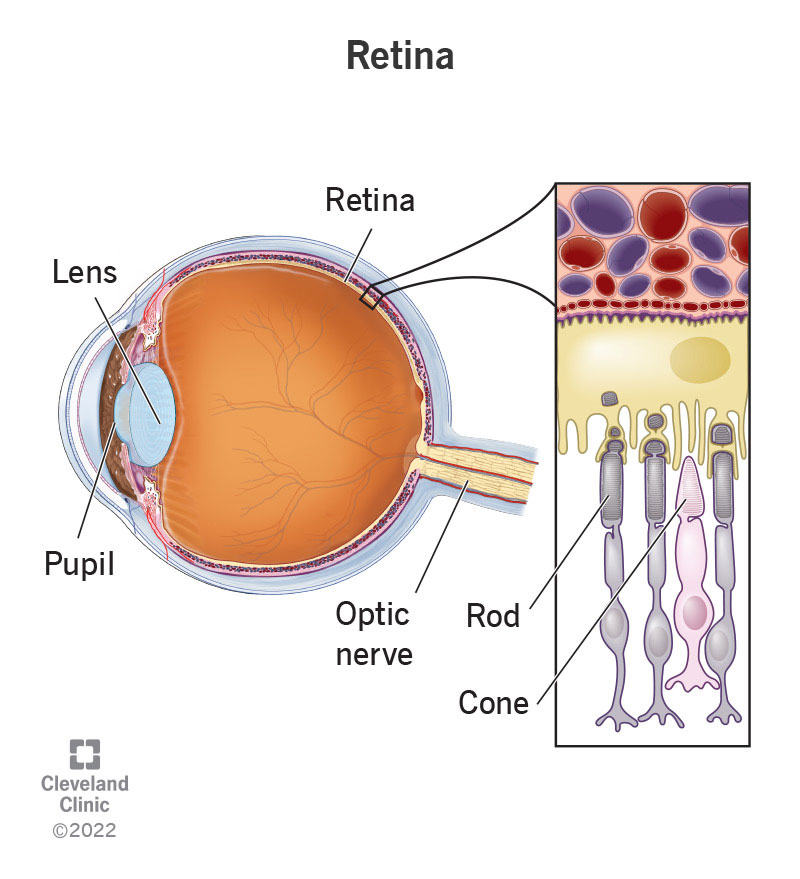

Our eyes are complex organs that pool information to give rise to our detailed vision. Vision begins with light, which is converted to electrical signals at the retina [2]. The retina is a specialized layer of the eye that covers the rear of the eyeball (Figure 2; [3]). It contains photoreceptors, more commonly known as rods and cones. These structures help the eye process visual information under a variety of lighting conditions [2]. The retina has a variety of different cell types organized into sub-layers that each play a unique role in visual processing. Eventually, neuronal projections called axons extend beyond the retina and communicate with the brain via the optic nerve.

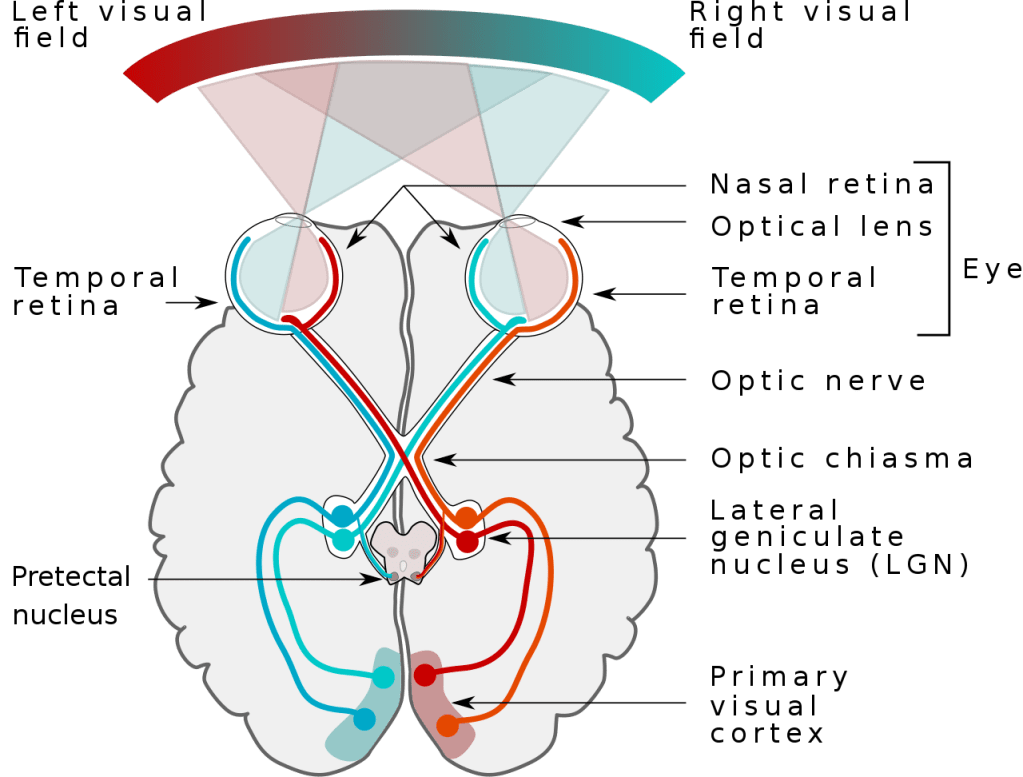

As a visual signal travels down the optic nerve, it decussates (i.e., crosses from one side to the other) at an area called the Optic Chiasm (Figure 3). Indeed, visual information is primarily processed in the hemisphere of the brain contralateral (opposite) to the eye of origin! Next, visual signal passes through the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus (LGN). The LGN is involved in color processing as well as determining relative position of objects in an eye’s field of view [4]. The destination of this pathway is the primary visual cortex, where a map of visual information is created [5]. The cortex also communicates with neighboring cortical areas and the LGN to modulate visual processing.

How deep is your visual field?

When it comes to perceiving and understanding depth, our visual system is well equipped to use the previously described toolkit to allow an individual to gauge the relative locations of many objects in their visual fields. As aforementioned, these tools can be either monocular or binocular visual cues.

Monocular cues

Although monocular vision is less accurate overall in perceiving depth accurately, there is a broad toolkit of cues one can discern from visual input from just one eye. Among these features are static, or unmoving, visual cues, as well as motion-based cues.

The first type of depth indication that can be perceived with monocular vision alone are cues from relative size and interposition of objects. Relative size is simple; a smaller object will appear further away than a larger, similar object. Additionally, if one has previous knowledge of the size of a familiar object, one can interpret a change in size as a change in distance. Picture a simple object, such as an apple – its average size is familiar, and if you see an apple that appears just a few centimeters tall, you will discern that it is further away from you. Secondly, interposition refers to the phenomenon of overlapping objects; the object in front will appear closer than the partially covered object [1]. For example, if you see a person standing in space, partially blocking your view of a car, you will likely interpret that the person is standing in front of the car. This is a simple yet useful way to reconcile the order of objects, even unfamiliar, in one’s visual field.

Additionally, cues from perspective may be used to appreciate depth. Linear perspective is a tool often used in art; when parallel lines converge in the distance, like a road growing smaller as it extends away from the viewer, a great sense of depth is created. This is because, in reality, when linear cues converge, we perceive them to be further away. Alternatively, aerial perspective relies on our color vision and blue light in the atmosphere. Scattered light in the distance causes a hazier, blue tinted visual experience when compared to nearer, more detailed objects in a clearer atmosphere. This perspective tool is also used frequently in art, when mountain ranges are often painted in a blue gradient to indicate distance (Figure 4; [1]; [6]). In addition to being cast in blue, objects in the distance also tend to lack detail that is perceivable in closer objects. This texture gradient is a useful tool to discern how far away an object is, as humans are deeply familiar with the amount of detail their vision is capable of detecting at key distances [7]. Lastly, light and shadows may be used to gauge depth; in typical circumstances, light originates from above, and directionally cast shadows provide information about the object’s location in space.

Monocular cues can also involve motion-based cues to measure depth. The concept of motion parallax refers to differences in perceived speeds of objects at varying distances from a viewer as they are also in motion. Imagine that you are in a train, moving at high speeds down the tracks – a nearby object, such as a fence, appears to fly past you as you chug along, while a faraway object such as the sun appears to follow along with you as you move. Nearby objects appear to quickly fly by, moving against the direction you are headed, while distant objects appear to move with the viewer, much more slowly (Figure 5).

Binocular cues

Despite the types of information our visual system can perceive with monocular vision, these cues are not always sufficient for accurate depth perception. These tools are most helpful when used in tandem and can be somewhat unreliable when used in isolation. Binocular vision pools detailed monocular input from both eyes, laterally spaced on either side of the nose, and creates a three-dimensional image and map of our visual field based on information from both perspectives. Try fixing your vision on an object, near or far, and close one eye at a time as you assess its location in space. Notice how it appears to bounce back and forth slightly, and consider the minutely different angle and perspective each eye provides. To make this exercise easier, you may hold out your thumb to block an object in the distance, and notice that as you close one eye, you may become able to see the hidden object. Despite our eyes being only a few inches apart, our eyeballs receive different enough information through the aforementioned cues that a much more detailed representation of its location in space can be constructed. This principle is known as retinal disparity [1].

Finally, our eyes also rely on convergence to assess depth, the degree to which the eyes angle inward toward one another to maintain a single binocular field of view [7, 8]. By angling our eyes towards the point of focus, one will maintain the ability to properly focus on an object and receive a clear visual image on the retinas. The degree of convergence is greater with closer objects, and lesser as objects move further away.

The Power of Adaptation

It has been shown in a number of classic studies that binocular vision is typically more reliable in calculating depth when compared to monocular vision in a series of lab-based tasks [9]. However, these studies were typically conducted in people with binocular vision who were temporarily forced to use monocular input by putting on an eye patch [9]. By forcing participants to temporarily rely on just one eye, instead of studying people with chronic monocular vision, these studies failed to acknowledge the role of adaptation. Despite the importance of binocular visual cues, people without binocular vision can still perceive depth proficiently through adaptation. In a study dating back to 1988, researchers interviewed patients who had recently lost one eye and thus had to rely on purely monocular vision. Following loss of one eye, 50% reported that they had acclimated to their new monocular vision in daily tasks such as walking, driving, and recreation in less than one month [10]. Even better, 93% of patients reported that they felt they were finished acclimating to their vision after one year [10]. Although less efficient than binocular vision, relying solely on monocular cues will still allow one to perceive depth.

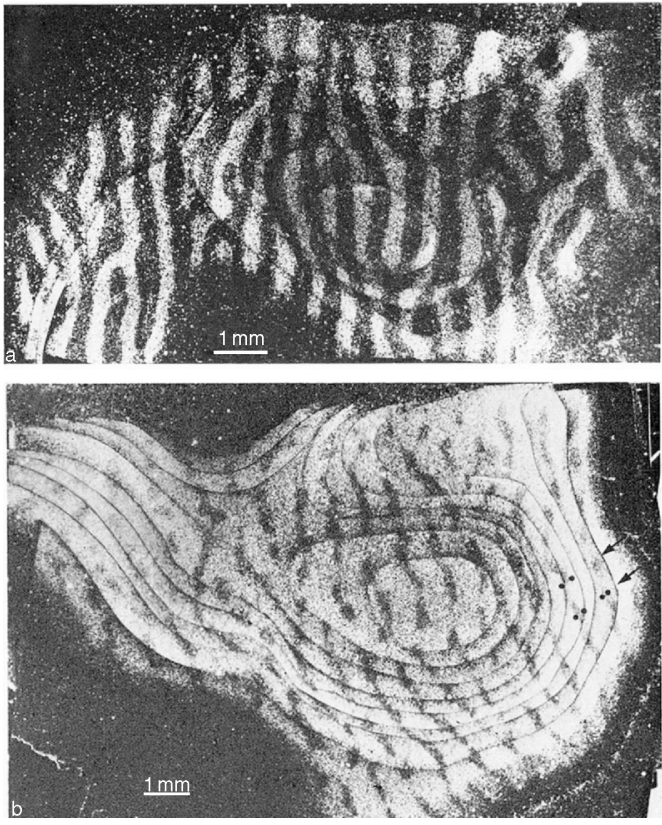

In organisms who lose vision in one eye early in life, stating that adaptation occurs is not solely a comment on behavior – it is a comment on the visual system’s biology. Research has shown that following monocular deprivation in a macaque during the animal’s early life, there is a significant change in representation of each eye in the visual cortex. This can take place during what is called a critical period, a time during which the brain is especially plastic for specific biological systems. In macaques with typical binocular vision, the visual cortex equally represents each eye (Figure 6a). By injecting dye into the functional eye of a macaque with binocular vision, this technique demonstrated the ocular dominance of the functional eye (Figure 6b, the white areas reflect the dyed representation of the injected eye) [11, 12]. Essentially, this showed that cortical representation of the deprived eye had all but vanished. This adaptation process prioritizes the functional eye for use of the cortex’s processing power. This work was foundational in the field of neuroscience, carried out by Drs. David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel in the 1970s.

Conclusion

Humans are resilient and dexterous, with the ability to adjust our motor actions in accordance with visual input. Independent of bi- or monocular visual input, in cases where one observes that an action has been miscalculated, one can adjust subsequent actions to account for the gap between perceived and observed distances. For example, if you reach for your coffee cup and end up grasping the space just in front of your mug, you will remedy this mistake by adjusting your perception of the cup’s distance from your body and reach further within seconds. Altogether, depth perception is an important tool for navigating the world around us, but it is not as simple as either having ‘good’ or ‘bad’ depth perception. We utilize multiple strategies – monocular and binocular – to interpret depth and learn how to interpret these cues quickly and subconsciously, and every living being develops their own repertoire of skills to navigate their own environments to the best of their ability.

References

[1] Kalloniatis M, Luu C. The Perception of Depth. 2005 May 1 [Updated 2007 Jun 6]. In: Kolb H, Fernandez E, Nelson R, editors. Webvision: The Organization of the Retina and Visual System [Internet]. Salt Lake City (UT): University of Utah Health Sciences Center; 1995-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11512/

[2] Troncoso, X. G., Macknik, S. L., & Martinez-Conde, S. (2011). Vision’s first steps: Anatomy, physiology, and perception in the retina, lateral geniculate nucleus, and early visual cortical areas. Visual Prosthetics, 23–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0754-7_2

[3] Nguyen KH, Patel BC, Tadi P. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Eye Retina. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542332/

[4] Lindstrom, S. & Wrobel, A. (1990) Intracellular recordings from binocularly activated cells in the cats dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus Acta Neurobiol Exp vol 50, pp 61–70

[5] Braddick, O. (2001). Occipital lobe (visual cortex): Functional aspects. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 10826–10828. https://doi.org/10.1016/b0-08-043076-7/03470-7

[6] Brooks, K. R. (2017). “Depth Perception and the History of Three-Dimensional Art: Who Produced the First Stereoscopic Images?”. i-Perception. 8 (1). Sage: 204166951668011. doi:10.1177/2041669516680114

[7] Monocular cues and binocular cues – AP psychology – what is depth perception?. YouTube. (2023, September 19). https://youtu.be/1zq6H3yzqGU?si=UcRcVnLUbf1uV1LY

[8] Cassin, B. and Solomon, S. Dictionary of Eye Terminology. Gainesville, Florida: Triad Publishing Company, 1990.

[9] Granrud, C. E., Yonas, A., & Pettersen, L. (1984). A comparison of monocular and binocular depth perception in 5- and 7-month-old infants. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 38(1), 19–32. doi:10.1016/0022-0965(84)90016-x

[10] Linberg, J. V., Tillman, W. T., & Allara, R. D. (1988a). Recovery after loss of an Eye. Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, 4(3), 135–138. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002341-198804030-00002

[11] Crair, M. C., & Shah, R. D. (2009). Long-Term Potentiation and Long-Term Depression in Experience-Dependent Plasticity. Encyclopedia of Neuroscience, 561–570. doi:10.1016/b978-008045046-9.01213-4

[12] Hubel DH and Wiesel TN (1977). Ferrier lecture: Functional architecture of macaque monkey visual cortex. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B: Containing Papers of a Biological Character 198: 1–59, with permission from The Royal Society

Motion parallax gif credit to Wikipedia.

You must be logged in to post a comment.