September

19

September

19

Tags

Solving the Puzzle of Addiction

According to the United Nations’s World Drug Report of 2024, the number of people who use drugs worldwide had risen to 292 million in 2022, a 20 percent increase over the past 10 years (1). Further more, an estimated 64 million of those people suffer from a substance use disorder (addiction). The study of addiction in neuroscience has proven useful in our understanding of addiction and ways in which to combat it, looking at the structures involved with rewarding behaviors. However, because addiction is such a complex disorder, modeling it in scientific research has been seen as inadequate, since the most common experimental paradigm used to study drug-seeking and drug-taking simply looks at drug self-administration through the lens of a simple stimulus-response behavior. However, researchers from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor developed a novel experimental model to study drug-seeking and taking behaviors that avoids the pitfall (2). To understand addiction’s hold on the brain and why we need to reimagine how we study it, let us look at how the brain rewards and motivates us to do things.

The Brain’s Motivator

You may have heard of dopamine as the “feel-good hormone” that rewards you (countless NeuWrite articles have talked about it: here, here, here, here, and here, among many others). However, that is far from the only role of dopamine in the brain. The brain’s dopamine reward center, the mesolimbic pathway, is typically thought to be the center of action for dopamine’s role in keeping people addicted to substances. However, the mesolimbic pathway is not the biggest culprit keeping people addicted. One key brain structure that mediates many of dopamine’s roles in addiction is known as the striatum.

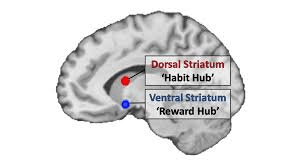

The striatum is a structure that lies beneath the outer layers of the brain, and it is subdivided into two sections that have quite different roles: the ventral striatum is the brain’s reward center that gets us motivated, and the dorsal striatum helps us perform actions by energizing and motivating us to obtain rewards (such as drugs) (3). The ventral striatum has long been associated with addiction, drug-seeking, and drug-taking behavior. However, the ventral striatum evolved to reward and motivate us to do much healthier things that may also be necessary for survival, like eat and reproduce. Drugs of abuse simply hijack this system and send it into overdrive, and that has the drawback of making addiction possible. However, it is not the ventral striatum alone that rewards us.

The other division of the striatum, the dorsal striatum, uses dopamine in a little bit of a different way than the ventral striatum. It motivates us to initiate movements by rewarding us with dopamine, and has two substructures: the dorsomedial striatum (DMS) and the dorsolateral striatum (DLS) (4). Although these two divisions both play a role in helping us execute actions, they take a slightly different approach to doing so, via goal-directed actions (DMS) or habits (DLS). Goal-directed actions are the actions we do every day where we consciously make an effort: you raise your hand in class to answer a question, you write an email to your boss explaining why you were late on the deadline for that project. Habits, on the other hand, are those actions that do not take much conscious effort for us to perform; they become second nature, like your daily morning routine when you’re getting ready for work. These two types of actions lay opposite each other, and thus are mediated separately. In fact, research has found that when you lesion the brain area responsible for one of these types of behavior, the other behavior is still present and takes more precedence (4). Researchers have also shown that, throughout training and habit acquisition, the transfer in excitation from DMS to DLS coincides with the change from goal-directed action to habit (4).

The “Drug Habit”: The Myth of Addiction as a Disorder of Habit

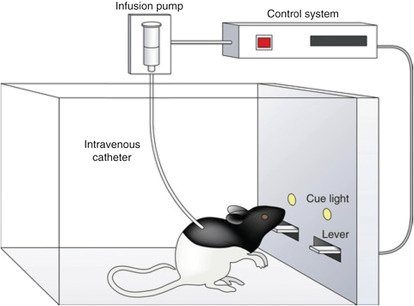

Although we have learned a lot about reward and motivation in the brain, some of the foundational but antiquated ways in which we study learning and addiction have had a lingering effect on the stigma of drug addiction. A classic experimental design for studying addiction is known as the drug self-administration task (5). In this design, a test subject (usually a rat) is trained to respond to specific stimuli in order to receive a dose of the drug being administered (commonly cocaine). Rats are trained to press a lever when an indicator such as noise or light goes off, and the drug is usually administered intravenously (IV) via lever press.

With this design, researchers can then vary many aspects of the experiment to study different things. This includes the rate at which the stimulus corresponds to an actual drug infusion and the amount of time the subject is allowed to administer the drug without restrictions. The problem with the drug self-administration paradigm when modeling addictive behavior, however, is that it models only a stimulus-response conditioned behavior and creates the notion of a “drug habit” (2). This contributes to the stigma surrounding those with addiction: people may view it as “just a bad habit” and falsely believe that it would be easy to simply terminate the habit. This likens addiction to a morning or bedtime routine, something we learn to do every day that just becomes second nature to us without requiring much mental effort (this is especially true with routines you can perform while still half-asleep). Addiction is not like this: drug-seeking and taking behaviors often require ingenuity and flexibility, especially in cases where the drug of choice is illicit and hard to obtain (2). That is why researchers from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, decided to develop their own cocaine self-administration procedure that better represents the nature of drug-seeking behavior in addiction: the puzzle self-administration procedure (PSAP).

SOLVING THE PUZZLE OF ADDICTION

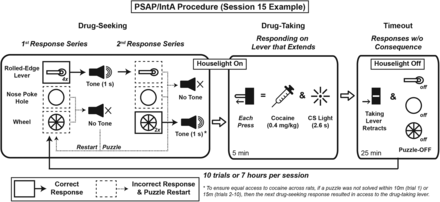

The classic drug self-administration model is a rather artificial model of addiction, not completely representative of drug-seeking behaviors outside of a lab. This is why Singer et al (2018) believed it was necessary to reimagine how we study addictive-like behaviors, using PSAP. PSAP serves as an updated model for addiction and drug-seeking behavior because it mimics the ingenuity and flexibility those with addiction must have to procure their drug of choice (2). In the study, PSAP requires rats to solve a unique puzzle each day to receive drug administration.

The study tested mice with PSAP for twenty days, with 10 trials per day. It was designed that puzzles increased in difficulty throughout the day, and each subsequent day. Each puzzle consisted of any number of lever presses, a nose pokes, and/or a wheel turns, and every puzzle switched up which task and how many times. For instance, on day 1, the rats simply had to perform one nose poke for the drug-taking lever to extend. On the otherhand, on day 20, they had to do 4 lever presses and 1 nose poke to self-administer the drug. Furthermore, each time a puzzle was failed, the rat had to restart it from the beginning. The idea behind having such elaborate procedures was to make it so the rats never formed a habit of drug-seeking and taking behaviors. Furthermore, by making the rats restart the puzzle every time they failed, it allowed the researchers to see if the rats would still persist in drug-seeking behaviors despite obstacles.

This is the key takeaway from the results of this study: drug-seeking/taking behaviors and addiction are not simple stimulus-response habits, both behaviorally and neurologically. The unique aspect that sets this drug self-administration procedure apart from the classic paradigm is the addition of the aforementioned puzzles. Rats’ adjustments in drug-seeking/taking behaviors (or lack thereof) is what distinguishes these addictive behaviors from stimulus-response habits. Put simply, researchers saw exactly what you would expect to see from a human being suffering from addiction: there was an increase in drug intake throughout the course of the experiment, and an increase in the rate in which the rats attempted the puzzles, even as they became more difficult and they failed more often.

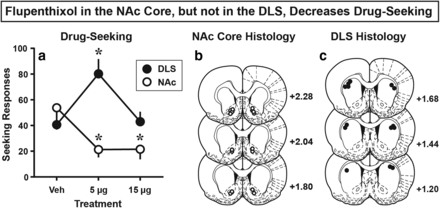

The next phase of this study looked at the neural mechanisms that underlie these self-administration behaviors. As previously mentioned, the ventral striatum is responsible for processing the reinforcement we get from rewarding stimuli – in this case, the euphoria from psychoactive drugs. This is the driving force behind drug-seeking, and as experimenters hypothesized, impairing this structure’s function in rats, along with the DMS, by administering a compound that inhibited dopamine functioning led to a reduction in drug-seeking behaviors (2).

Interestingly enough, impairing the DLS, the region responsible for habitual behaviors, had two different effects on drug-seeking, depending on the degree to which researchers impaired this region (size of the dose). At a high-dose, there was no change in the drug-seeking behavior. Most puzzling of all, when a low dose of this inhibiting compound was administered, there was actually an increase in drug-seeking behaviors. If drug-seeking were a habit, this would most likely not be the case, and drug-seeking behaviors would be expected to reduce. If drug-taking were a habitual stimulus-response behavior, drug-seeking behavior would not be affected when the ventral striatum and DMS are impaired, and it would be when the DLS is. However, that is the opposite of what Singer et al. found. Because of these puzzling findings, researchers speculate that the control and regulation of drug-seeking behaviors is much more complicated than we think. However, with PSAP, researchers were able to conclude that drug-seeking behaviors are not solely stimulus-response habits (2), it seems that we can lay to rest the myth that addiction is a “drug habit”.

CONCLUSION

In today’s world, substance abuse is becoming a problem with devastating impact on people’s lives around the globe, leading someone organizations to call it an “international crisis” (6). In 2022, an estimated 2.7 million people were prosecuted for drug offenses, and only 1 in 11 individuals with a substance use disorder are in treatment. The number over drug-related deaths is increasing dramatically with more potent drugs being synthesized all the time, underscoring the need for more research on addiction and resources out there to those struggling with addiction. We must improve our methods until research on addiction can provide us with more effective ways to treat and prevent addiction so we can save lives, and this research seems to be a step in the right direction

References

- https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/press/releases/2024/June/unodc-world-drug-report-2024_-harms-of-world-drug-problem-continue-to-mount-amid-expansions-in-drug-use-and-markets.html

- https://www.jneurosci.org/content/38/1/60

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959438811000389

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0896627313008052

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/drug-self-administration#:~:text=Drug%20self%2Dadministration%20refers%20to,a%20drug%20as%20a%20reinforcer.

- https://www.overdoseday.com/facts-stats/

You must be logged in to post a comment.