October

30

October

30

Tags

What Dreams Are Made Of

Introduction

Dreaming is a mystical phenomenon. Dreams can take you on magical adventures, allowing you to soar through the sky and discover new worlds. They can also be more earnest, allowing you to relive experiences with loved ones, or imagine how a situation in waking life may have gone if different decisions were made. As such, dreams are thought to have deeply rooted connections with memories and emotions. While dreams are difficult to research due to their reliance on surface-level and non-invasive clinical or psychological studies, many theories regarding the origins and purpose of dreams have been proposed over the years. The debates are ongoing, but at the foundation of these theories, one statement prevails; the involvement of dreams in processing memories and emotions, as well as inspiring creativity, gives dreams an important role in regulating humanity’s emotional and psychological well-being.

Breaking Down Sleep

Sleep States

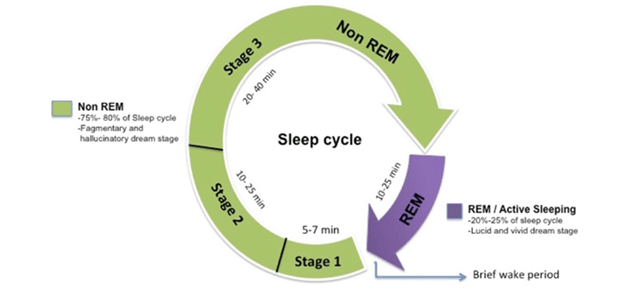

When the body is asleep, it cycles between various unique sleep stages. Each stage in the sleep cycle has a specific purpose in maintaining a person’s physical and psychological well-being. To achieve these specific purposes, the activity in the brain and body in each state continually changes. One common way researchers have broken down the sleep cycle is by dividing sleep into either rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep and non-rapid-eye movement (NREM) sleep. Throughout the night, the body undergoes approximately 4-5 cycles of NREM and REM with each cycle lasting around 90 – 120 minutes (Figure 1) (“Sleep,” 2023).

NREM Sleep Stages

NREM sleep can be broken down into three stages. Stage 1 accounts for approximately 5% of a night’s sleep and is typically thought of as the lightest stage of sleep. This is often the stage people first experience when beginning to fall asleep or wake up (“Sleep,” 2023). The following stage, stage 2, accounts for approximately 45% of time spent sleeping and is characterized by slightly deeper levels of sleep. During stage 2, the body temperature drops, muscles relax, breathing is slowed, heart rate decreases, and eye movements stop (Suni & Singh, Abhinav, 2023). These physiological changes are accompanied by changes in neural activity. At this time, activity in the brain generally slows with the exception of a few short, but powerful, bursts of activity. It is theorized that these bursts of activity are involved in organizing memories from waking life (“Sleep,” 2023). Stage 3 of NREM accounts for approximately 25% of an adult’s time spent asleep and is thought to be the deepest sleeping stage of NREM (“Sleep,” 2023). During stage 3, the body relaxes even further as the muscle tone, pulse, and breathing rate decrease. This stage is theorized to play a vital role in injury repair, boosting the immune system, storing memory, and eliciting creative and insightful thinking (Suni & Singh, Abhinav, 2023).

REM Sleep State

REM sleep makes up the remaining 25% of a typical night’s sleep (“Sleep,” 2023). The body and brain act much differently in REM sleep than in NREM. During REM, the level of activity in the brain increases to a level nearing wakeful thought. At the same time activity in the brain picks up, sensation and movement in the body rapidly decline. In REM, many of the brain’s senses are blocked and muscles throughout the body are temporarily paralyzed. Exceptions to this paralysis, however, are made by the muscles controlling the movement of the eyes. Instead, during REM, the eyes can be seen doing rapid movements underneath the eyelids. This unique feature is what gave REM its name. While it may seem odd that the body undergoes muscle paralysis and decreased sensation at this stage even though the neural activity in the brain nears that of wakeful thought, these features of REM serve an important function. Decreased sensation and muscle paralysis serve to limit the amount of signaling regarding external information from entering, getting processed by, and leaving the brain. By doing this, cognitive thought surrounding external information is essentially blocked. This is believed to allow the mind to direct more energy towards internal processes and enhance REM’s involvement in memory, learning, creativity, and dreaming. (Suni & Singh, Abhinav, 2023).

Stages of Dreaming

REM and NREM are often studied under the lens of dreaming and non-dreaming sleep. While dreaming can occur in both REM and NREM sleep stages, REM is the state people typically associate with dreaming. Over the past few decades, studies have shown REM is associated with higher frequencies of dream recall, and dreams in this stage are typically longer, hold more intense emotions, and can be quite bizarre. In contrast, NREM dreams are less commonly remembered upon waking and are typically shorter, fragmented, and thought-like (Horton, 2017). As a result, studies on the generation and processing of dreams tend to be focused on dreams occurring during REM.

The Theories Behind Dreaming

PGO Waves

The main types of cells that transmit information through the brain and spinal cord are called neurons. Neurons are able to transmit information about the internal and external environment by passing along electrical signals from one neuron to the next. When neurons’ electrical activity becomes synchronized, they can create rhythmic and repetitive voltage oscillations across brain regions. These neural oscillations are commonly known as brain waves (Buskila et al., 2019). One type of brain wave believed to play a vital role in creating dreams is ponto-geniculo-occipital (PGO) waves (Gao et al., 2023).

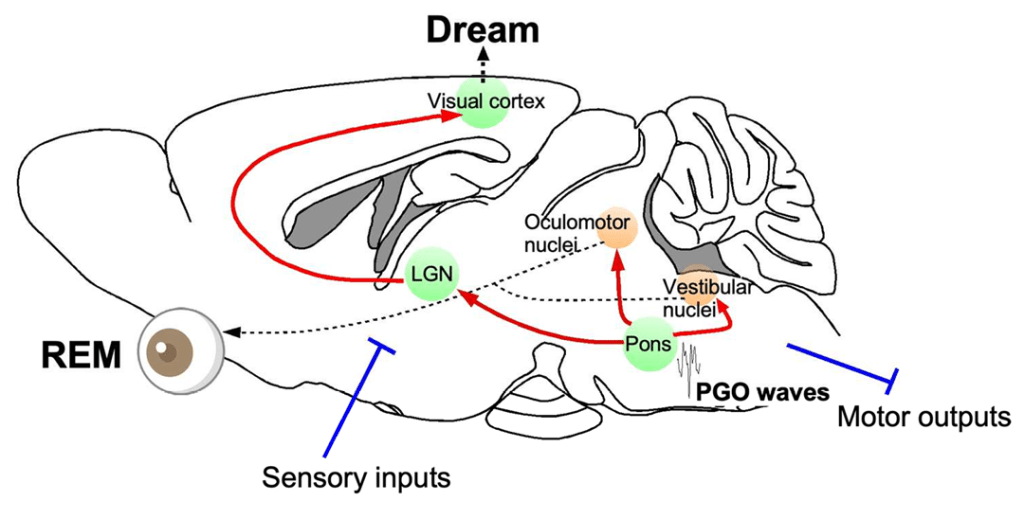

This waveform activity was discovered in the late 1950s and early 1960s by researchers looking at cerebral electrical activity during sleep in cats (Bizzi & Brooks, 1963; Brooks & Bizzi, 1963; Jouvet & Michel, 1959), and was later coined “PGO waves” after the neural pathway they initiate in the brain. PGO waves originate in a region of the brainstem known as the pons (P). The pons is known to be involved in many of the body’s essential functions, including sleep cycle regulation, pain signal management, balance, movement, and breathing (“Pons,” 2022). PGO waves are formed by burst firing from the pons just before the onset of REM and are produced continually throughout the duration of REM. PGO wave activity is then sent to a region of the brain’s visual thalamus known as the lateral geniculate nucleus (G), a brain region thought to transmit visual information to the central visual system for the detection and recognition of shape, color, and motion (Krauskopf, 1998). PGO waves are also sent to the occipital cortex (O), which is widely associated with visual processing (Rehman & Khalili, 2023), as well as other various regions of the brain (Gao et al., 2023; Tsunematsu, 2023).

These waves are a signature of REM sleep and are believed to be involved in generating dreams through their visual pathway. Dreaming is thought to be a result of memory information passing through the PGO wave’s visual pathway, resulting in the memory information being interpreted by the brain as visual information and leading to the visual hallucinosis of dreams (Gao et al., 2023).

Activation Synthesis Model

The activation-synthesis model was initially created based on recordings of PGO wave activity in cats by Hobson and McCarley in 1977 (Hobson & McCarley, 1977). This model breaks dreaming into two processes: activation and synthesis. According to this theory, dreams are created due to the random activation of the pons in the brainstem. The pons, then, send information to downstream regions of the brain, such as the lateral geniculate nucleus and the visual cortex (Figure 2). When this process occurs in the absence of external stimuli, internal inputs are able to randomly activate sensorimotor information to create the perceptual, conceptual, and emotional realities perceived in dreams. The association between a neural network space with an absence of external stimuli and increased internal activation of sensorimotor information for dream formation is thought to be why dreams are much more frequent and intense in REM sleep, where sensory inputs and motor outputs are silenced or blocked (Gao et al., 2023; Tsunematsu, 2023). Later, the hypothesis was improved upon to include emotional appraisal to visual cortex activation and dream generation (Seligman & Yellen, 1987).

Activation, Input, & Modulation (AIM) Model

The AIM Model, proposed by Hobson et al. in 2000, evolved from the Activation-Synthesis Model to explain similarities and differences in the experiences of the waking state, NREM, and REM (Hobson et al., 2000). AIM here stands for Activation, Input, and Modulation. Activation refers to the capacity of the nervous system to process information, with the thought that dreaming occurs during sleep when cortical arousal exceeds a certain threshold, regardless of the stage of sleep. Input refers to how much information is being processed by the brain and whether that information originates internally or externally. Lastly, modulation describes how neural processes are influenced by chemicals in the brain called neurotransmitters and neuromodulators.

In this model, the awake state has a high activation level, input is externally dependent, meaning a significant portion of the brain’s energy is directed toward processing information gathered from the outside world, and the brain’s neuronal processing system is heavily influenced by a group of neurotransmitters called monoamines. NREM, despite being a sleeping state, experiences few hallucinatory activities due to its weak activation and modulation levels and both external and internal information input processing capabilities. In contrast, REM experiences more frequent and vivid dreaming due to high activation levels, its shift from external to internal information-dependent processing, and its cholinergic neurotransmitter dominant modulation system (Tsunematsu, 2023).

Dopaminergic Forebrain Mechanism

While many believe that dreaming originates in the brainstem, it has also been hypothesized that the forebrain controls dream generation. It has been shown that REM and dreaming are dissociable states, so in this alternative theory, it is proposed that the foundational generation of REM and dreaming may be different as well. Here, the brainstem is believed to control REM sleep and is only one of the factors that can activate the forebrain to initiate dreaming. The forebrain is also activated by a part of the brain called the mesocortical-mesolimbic dopamine system. This part of the brain is also known as the “seeking system” and is widely thought to be involved in emotional anticipation and behavior motivation. As a result, this region is thought to convey the emotional drive and motivation involved in dream generation, increasing dream activity during heightened emotional states in both REM and NREM stages (Gao et al., 2023).

Conclusion

Despite the immense difficulty researchers face when studying the neural mechanisms behind how we dream, researchers are continually finding new, innovative ways to further understand the sleeping mind. New theories are constantly being developed and expanded upon, opening debates on which theories lie closest to the truth. As more research comes out, our knowledge of the mind will continue to grow, and with that, we come closer to understanding a pivotal part of what makes us all human.

References

Bizzi, E., & Brooks, D. C. (1963). FUNCTIONAL CONNECTIONS BETWEEN PONTINE RETICULAR FORMATION AND LATERAL GENICULATE NUCLEUS DURING DEEP SLEEP. Archives Italiennes De Biologie, 101, 666–680.

Brooks, D. C., & Bizzi, E. (1963). BRAIN STEM ELECTRICAL ACTIVITY DURING DEEP SLEEP. Archives Italiennes De Biologie, 101, 648–665.

Buskila, Y., Bellot-Saez, A., & Morley, J. W. (2019). Generating Brain Waves, the Power of Astrocytes. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 1125. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.01125

Gao, J.-X., Yan, G., Li, X.-X., Xie, J.-F., Spruyt, K., Shao, Y.-F., & Hou, Y.-P. (2023). The Ponto-Geniculo-Occipital (PGO) Waves in Dreaming: An Overview. Brain Sciences, 13(9), 1350. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13091350

Hobson, J. A., & McCarley, R. W. (1977). The brain as a dream state generator: An activation-synthesis hypothesis of the dream process. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 134(12), 1335–1348. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.134.12.1335

Hobson, J. A., Pace-Schott, E. F., & Stickgold, R. (2000). Dreaming and the brain: Toward a cognitive neuroscience of conscious states. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23(6), 793–842; discussion 904-1121. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x00003976

Horton, C. L. (2017). Consciousness across Sleep and Wake: Discontinuity and Continuity of Memory Experiences As a Reflection of Consolidation Processes. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 159. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00159

Jouvet, M., & Michel, F. (1959). [Electromyographic correlations of sleep in the chronic decorticate & mesencephalic cat]. Comptes Rendus Des Seances De La Societe De Biologie Et De Ses Filiales, 153(3), 422–425.

Krauskopf, J. (1998). Color Vision. In AZimuth (Vol. 1, pp. 97–121). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1387-6783(98)80006-8

Krishnan, D. (2021). Orchestration of dreams: A possible tool for enhancement of mental productivity and efficiency. Sleep and Biological Rhythms, 19(3), 207–213.

Pons. (2022). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/23003-pons

Rehman, A., & Khalili, Y. A. (2023). Neuroanatomy, Occipital Lobe. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544320/

Seligman, M. E., & Yellen, A. (1987). What is a dream? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 25(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(87)90110-0

Sleep. (2023). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/12148-sleep-basics

Suni, E., & Singh, Abhinav. (2023). Stages of Sleep: What Happens in a Sleep Cycle. Sleep Foundation. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/stages-of-sleep

Tsunematsu, T. (2023). What are the neural mechanisms and physiological functions of dreams? Neuroscience Research, 189, 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures.2022.12.017

Cover Image Source

You must be logged in to post a comment.