July

23

July

23

Tags

Deep Depths and Breaths

Keep Holding On

How long can you hold your breath for? Is it over two minutes? Pretty impressive–now imagine holding your breath for that long while sinking deeper and deeper below the dark depths of the ocean, reaching distances of 100 feet (about the length of a 10-story building), while thousands of pounds of water accumulate and press on top of you. Think you could still match your personal record?

The average human can hold their breath for 30-90 seconds underwater while remaining static. This is completely independent of the challenge of swimming, which is an energy expenditure, and of additive water pressure on the body, which has a multitude of physiological effects that are also costly. For years, I have been fascinated by deep sea divers and their ability to defy the body’s natural physiology, going to the depths of not only the ocean but of human limits. In this article, we are going to submerge ourselves in the science of freediving, while I attempt to include as many diving-related puns as possible. Let’s jump in!

Deepest Man in the World

The Guinness World Record for “No Limits” freediving is set by Herbert Nitsch, an Austrian freediver who reached an astounding 831 feet (253 meters) diving record in Santorini, Greece in 2012 during a project labeled ‘Extreme 800’. That’s equivalent to over two-and-a-half Statues of Liberty, or just over three-fourths the height of the Eiffel Tower. The No Limits event involves the use of a weighted sled to descend as far as possible and uses an air-filled balloon or other buoyancy device to return to the surface. This is considered the most dangerous of the freedive events, as it involves a much more rapid descent and ascent than an unassisted free dive, or one requiring a variable weight.

Fig 1. Graphic from Nitsch’s 2007 No Limit freedive record of 702 ft (214 m). He beat this record by 127 ft (39 m) in 2012 with a project labeled ‘Extreme 800’, in which he surpassed the project’s aim of 801 feet, reaching 831 ft (253 m).

A Perilous Plunge

Just 10 minutes after Nitsch resurfaced from breaking the world record in 2012, he began to experience serious symptoms of decompression sickness, a common risk due to rapid pressure changes, such as when a diver ascends too quickly from a dive. He was rushed to the hospital where he incurred multiple brain strokes due to severe decompression sickness. His initial medical report suggested he would no longer be able to walk without assistance and that he would require home care for life. However, through extensive rehabilitation, he made a strong recovery. He still has balance and coordination problems on land, but does not experience them underwater. He continues to deep free dive.

Situations like the one Herbert Nitsch experienced during what could have been his last dive ever are unfortunately not uncommon for deep sea divers. So, what contributed to Nitsch’s nearly fatal accident, and what are the physiological processes involved in a deep sea dive?

Buoyancy Basics

Deep sea divers are not performing these challenging descents by simply plugging their noses and hoping for the best; it’s their ability to alter their CO2 and O2 composition and enter a meditative state that enables them to 1) maximize their oxygen stores to surpass average limits of an underwater breath hold and 2) regulate their blood flow or beats per minute (BPM) to maintain their composure as they glide through layers of ocean. So how is the human body capable of this? To break down what happens below the surface of these deep divers, two principles in physics should be understood:

the first is Boyle’s Law, an experimental gas law that describes the relationship between pressure and volume of a confined gas. According to Boyle’s Law, when pressure goes up, gasses lose volume, thus the deeper they dive, the smaller the lungs get.

The second is Henry’s Law, which states the amount of dissolved gas in a liquid is directly proportional at equilibrium to its partial pressure above the liquid. For example, pressure builds up as swimmers dive deeper, causing an increase of gas molecules, nitrogen and carbon dioxide, to flow into the bloodstream. This causes many divers to experience a type of high, known as narcosis.

These two laws of physics are imminent in the physiological changes that swimmers undergo during submersion, which, like their lungs, I’ll expand on. When humans submerge their faces in cold water an automatic response called the Mammalian Dive Reflex (MDR) is triggered. MDR consists of four main processes:

- Bradycardia – Slowing of the heart, decreasing heart rate (beats per minute), which preserves oxygen levels.

- Peripheral Vasoconstriction – Narrowing of blood vessels in extremities of the body like legs and arms, providing more blood circulation for vital organs, such as the lungs, heart, and brain.

- Blood Shift – Cushioning of lungs with blood at residual volume (when lungs cannot get any more compressed), where blood vessels surround the alveoli of the lungs to protect them from extreme or fatal compression.

- Spleen Contraction – Contraction of the spleen occurs, which releases oxygen-rich blood cells (hemoglobin) and aids in longer breath holds.

These components together make up the MDR physiological adaptations that our bodies automatically initiate to allow a longer and deeper breath hold underwater. Learning how to optimize these abilities through regimented training in breath hold and oxygen preservation are crucial to the success of these athletes.

For more information, or to view a brief YouTube clip on freediving, click this link.

The Bewildering Brains of Deep Sea Divers

Despite the high fatality rates and well-known risks of free diving, these athletes are not dissuaded from striving for breathtaking depths. Does that make them more brave or cognitively resilient than those who do not participate in this sport? To find out what makes the brains and behavior of these aquatic super-humans different from land lovers, air admirers—regular people, let’s take a look at the brain of a trained deep sea diver.

So, what does the brain of a trained deep sea diver look like? In a study by Annen, et al., 2021, researchers used electroencephalography (EEG) and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to investigate the psychological and physiological adaptation and the functional cerebral changes during six-and-a-half minutes of dry, static apnea (temporary breath hold without moving) in a world champion freediver. They found that during voluntary apnea, the trained diver showed extreme adaptability.

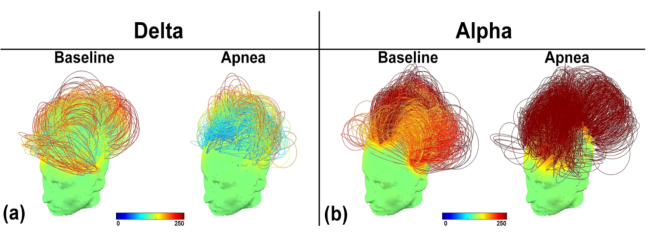

Fig 6. EEG-based connectivity in the delta (a) and alpha (b) frequency bands, during baseline and apnea conditions.

The height and color of the arcs represent connectivity strength, where low arcs and blue/yellow colors represent weak connectivity and high arcs with orange/red colors represent strong connectivity.

As shown in Fig 6., higher connectivity was correlated with alpha bands during apnea states. Alpha is the level of frequency in brain activity that is related to cognitive processes like relaxation, attention, and cognitive performance. Alpha-band oscillations are involved in suppressing distracting information and enhancing attention to relevant stimuli, especially in the occipital cortex, which is where visual processing occurs. This is evident in tasks that require selective attention across different sensory domains. Among these tasks, alpha activity is associated with relaxation and calm, whereas there is much less prominent alpha during the resting, unfocused baseline. Delta waves were higher during baseline compared to apneatic state. Thus, where alpha is correlated with focus, delta occurs during periods of lack of focus or impaired attention, as seen in the unfocused baseline state compared to apneatic.

Fig 7. Significant differences in regional connectivity between the baseline versus apnea in the delta band (c) and alpha band (d) were observed (p < 0.05, FDR corrected).

The scalp color represents the number of connections (i.e., degree) of each node (i.e., electrode). Blue lines represent decreased connectivity, which were observed in the delta band over the left hemisphere and posterior interhemispheric connections. The red lines represent increased connectivity during apnea as compared to baseline, mainly observed between regions within the right hemisphere as well as for interhemispheric connections.

Fig 7. shows that compared to resting state at baseline, apnea (breath holding) was correlated with increased EEG power and functional connectivity in the alpha band (d), and decreased delta band connectivity (c). Connectivity during the fMRI scan was increased within the default mode network, which is associated with mind wandering/daydreaming, and within visual areas, whereas, in the precentral cortex, which is involved in voluntary motor movements and the postcentral cortex, involved in sensory information processing, connectivity was decreased. This sheds light on how champion free divers’ brains function during apneatic activity; neural activity is increased in the future planning centers of the brain and decreased in the peripheral body. Interestingly, these changes overlap with cerebral signatures of meditation practices. Based on these findings along with the self-reports from this study, it is suggested that professional free divers have the ability to create a state of sensory dissociation when performing prolonged apnea, potentially contributing to their zen-like state during what would normally be considered stressful situations.

Cardiovascular Capabilities

In a different study by McKnight, et al., 2021, they used near-infrared spectroscopy to measure cerebral and systemic cardiovascular responses to deep, breath-hold diving in elite freedivers. Impressively, this team of researchers was able to capture the biophysical patterns of breath holding in real time during participant dives. Not only did this study capture these haemodynamic and oxygenation changes in humans, they were also able to apply their technology to gray seals. A side by side comparison of the breathing dynamic in the two subject types is shown below.

Fig 8. The cardiac pulsation of [ΔHbT] for one example dive (a) is compared to the resting state cardiac pulsation in a grey seal (b). The color correlates with the underlying heart rate, meaning that during breath holding, heart rate slows (yellow) and the cardiac pulse magnitude increases (y-axis). Meanwhile, prior to breath hold, the heart rate is high (red) and pulsation magnitude is low.

This figure shows how the human diver and grey seal compare in cardiac pulsation magnitude, which is essentially the strength or amplitude of the pressure wave caused by the heartbeat as it travels through the body. Similarly, both examples show a heightened heartbeat and lowered magnitude cardiac pulsation prior to and during the initial breath hold, as well as decreasing the heart rate and increasing magnitude as time of the dive goes on. Interestingly, aquatic mammals perform similarly to humans, which bolsters the idea of the mammalian diving reflex as described earlier.

Super Human or Super Training?

Now that we have revealed the functional and encephalographical workings of a professional diver, we can unpack the differences between trained divers and non-divers. In a study conducted by Ratmanova et al. in 2016, trained freedivers (N = 13 men) and non-trained participants (N = 9 men) underwent static, breath-holding tests to reveal the influence of prolonged breath-holding on multiple psychophysiological outcomes like heart rate and respiratory variables, brain activity, and cognitive functions.

Findings showed significantly decreased heart rate in trained divers, compared to non-divers, with the average duration of breath-holding for divers being 265 seconds vs 180 seconds for the non-divers. Interestingly, both groups showed a substantial decrease in alveolar oxygen partial pressure (PA O2) and a notable increase in alveolar carbon dioxide partial pressure (PA CO2), indicating peripheral vasoconstriction for air preservation as occurs in MDR. Moreover, trained divers demonstrated a greater decrease in PA O2 compared to the non-divers, potentially revealing why they were able to hold their breath longer. PA CO2 values remained similar between both groups at the end of the breath-holding.

Trained divers also showed considerably lower arterial oxygen levels (SpO2), which is a marker of how well oxygen is being transported to peripheral parts of the body.

Fig 9. Changes in haemodynamic parameters induced by breath-holding. (a) Arterial blood oxygenation (SpO2); (b) brain tissue oxygenation index (TOI).

Contrary to the initial hypothesis that prolonged apnea would cause cerebral hypoxia, the study found that brain tissue oxygenation index (TOI) remained relatively stable up to the end of apnea in both divers and non-divers, with no significant differences between the groups.

This incredible maintenance of brain oxygenation, even with severely decreased SpO2, is attributed to specific compensatory mechanisms that were shown to be much more prominent in trained breath-hold divers. These mechanisms are similar to the diving responses aimed at centralizing blood circulation and reducing peripheral oxygen uptake. Brain tissue hemoglobin was significantly increased in both groups during breath-holding, but impressively, the increment was significantly higher in the trained diving group, suggesting a higher cerebral blood flow in divers compared to non-divers.

Lastly, the attention and cognitive performance was measured for both groups. The initial attention level and speed of processing measured prior to breath-hold were similar in both groups.

Fig 10. Results of the letter cancellation task, i.e., attention task, in breath-hold divers (D group) and non-divers (C group) before and after holding their breaths.

There was no decrease in attention level or speed of processing immediately after breath-holding in either group. In fact, the attention level significantly increased in both groups after prolonged apnea, with some non-divers reaching 100% on the attention test. Among attention, the anxiety level of participants was also measured. The trait anxiety level of divers was significantly lower than that of control subjects, while state anxiety was similar in both groups.

In summary, the study concluded that apnea up to 5 minutes did not cause notable cerebral hypoxia or a decrease in brain performance in either group. Instead, compensatory mechanisms, particularly enhanced in trained divers, seem to maintain brain oxygen supply despite significant drops in arterial oxygen levels.

Sub-Merging it all Together

From the depths of one of my greatest fascinations, we’ve just scratched the surface of what makes deep sea divers so impressive. With the lung-crushing depths they reach and their brainwave-calming meditations, the world of freediving is as much about mental mastery as it is about physical adaptation. We explored how the mammalian dive reflex, cardiovascular control, and breath-hold training push the limits of human endurance, while neural shifts in alpha and beta waves reveal a cognitive calm beneath the chaos. Whether it’s a lower resting heart rate, enhanced attention, or reduced anxiety, elite freedivers train their minds and bodies to perform where most would panic.

And while most of us may never descend 800+ feet into the ocean’s abyss, understanding these adaptations reminds us that deep breaths—whether underwater or on dry land—can help us stay centered, sharpen focus, and keep calm when life gets heavy. So, whether you’re diving into the deep or just your daily to-do list… don’t forget to breathe.

REFERENCES:

- Mapping the functional brain state of a world champion freediver in static dry apnea –

- Annen, J., Panda, R., Martial, C. et al. Mapping the functional brain state of a world champion freediver in static dry apnea. Brain Struct Funct 226, 2675–2688 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-021-02361-1

- When the human brain goes diving: using near-infrared spectroscopy to measure cerebral and systemic cardiovascular responses to deep, breath-hold diving in elite freedivers –

- McKnight, J. C., Mulder, E., Ruesch, A., Kainerstorfer, J. M., Wu, J., Hakimi, N., … & Schagatay, E. (2021). When the human brain goes diving: using near-infrared spectroscopy to measure cerebral and systemic cardiovascular responses to deep, breath-hold diving in elite freedivers. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 376(1831), 20200349. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0349

- Prolonged dry apnoea: effects on brain activity and physiological functions in breath-hold divers and non-divers –

- Ratmanova, P., Semenyuk, R., Popov, D. et al. Prolonged dry apnoea: effects on brain activity and physiological functions in breath-hold divers and non-divers. Eur J Appl Physiol 116, 1367–1377 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-016-3390-2

- How MDR works in freediving (content and cartoons screenshotted) –

- Wiki Herbert Nitsch –

- Screenshots (2) from video of MDR (underwater cartoons) –

- Breath-hold physio explained –

- Fitz‐Clarke, J. R. (2018). Breath‐hold diving. Comprehensive physiology, 8(2), 585-630. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c160008

You must be logged in to post a comment.