August

29

August

29

Tags

The Neuroscience of the Breath

The Neuroscience of the Breath

Scientists search to uncover the mind-body connection

Mind-body practices, which stem from traditions originating in countries such as India, China, and Tibet, have become increasingly popular in Western society. These practices, which include yoga, meditation and tai chi, revolve around breathing techniques or pranayama- learning to control the breath to shift from an anxious state of mind to a relaxed one.

Contemplative practitioners believe that the breath holds the ability to alter the mind. A growing desire to decipher this mysterious physical-psychological relationship, fueled in part by mainstream popularity, has led to a significant increase in scientific interest in mind-body practices over the last twenty years. From 1997-2006, there were only 2,412 peer-reviewed publications pertaining to mind-body practices. This number increased to 12,395 between 2007-2016, and clinical studies have followed a similar projection [1].

The number of peer-reviewed scientific publications on contemplative activity from 1945-2017. [1]

Throughout this short period of time, scientific studies have described the numerous benefits yoga and meditation practitioners gain such as increased physical health, mental health and cognitive abilities. Commonly observed positive physiological effects include a decrease in heart rate, blood pressure and inflammation, along with improved balance and strength [1]. There are also decreases in psychological symptoms of depression, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and pain. Furthermore, it is thought that meditation can act as a buffer against age-related decline by enhancing working memory and decision-making [1]. Yet, the underlying mechanism of how the breath affects physical and mental health remains elusive.

Photo by Erik Brolin.

One uniting factor across multiple disciplines of mind-body exercises is the focus on the breath. In most cases, the practitioner aims to slow the rate of breathing with particular attention on increasing the length of the exhalation (some exceptions do exist, such as “breath of fire,” which is rooted in kundalini yoga). Through practices such as yoga and tai chi, practitioners often aim to sync their breath with steady movement, thereby increasing the link between the internal body and the external world. Rhythmic, slow breathing increases oxygen uptake [1], which is relayed to the body’s autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system acts to keep the body in a type of balance or equilibrium called homeostasis.

Mind-body exercises, such as meditation and restorative yoga, engage multiple aspects of the autonomic nervous system. During these practices, the parasympathetic and enteric nervous systems, also known as the “rest and digest” systems, become more active, acting to lower heart and respiration rate while increasing digestion. In contrast, the sympathetic nervous system becomes less active. It is responsible for the “fight, flight or freeze” response, and can raise heart rate, blood pressure and respiration rate to provide the organism with immediate energy.

What connects the breath to these nervous systems? Scientists have proposed a neurophysiological model of the breath that relies on relaying communication by the vagus nerve. This nerve connects the heart, lungs and digestive tract to the brain by way of the parasympathetic nervous system. The vagus nerve is responsible for sending and receiving signals about bodily states. It is thought that the enteric nervous system can also communicate with the brain through the parasympathetic nervous system by means of the vagus nerve.

Researchers believe that slow, deep breathing directly activates the parasympathetic nervous system via the vagus nerve through signals sent from stretch receptors in the lungs. When the practitioner takes a deep breath, these receptors are triggered. This respiratory biofeedback could be signaling a state of relaxation to the breathing control center of the brain, located in the brainstem. The brainstem could then respond by sending signals out to decrease stress. Scientists note that this mechanism could explain many of the observed positive effects on mental and physical health after meditating or practicing yoga.

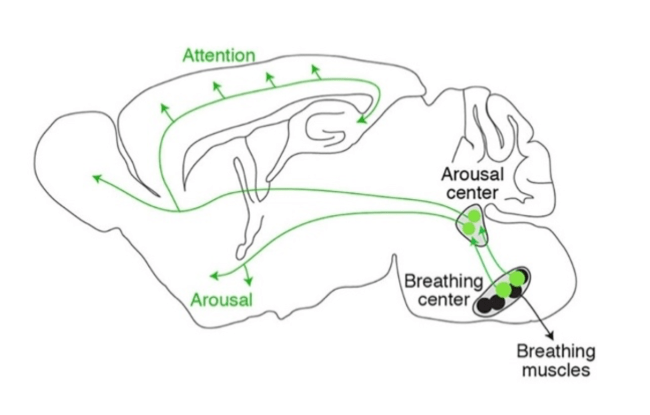

In a recent study from Stanford University, the Mark Krasnow lab showed that this theory may be correct [2]. They identified a group of neurons in the mouse brain that connect the brainstem’s breathing center to parts of the brain involved in arousal and attention. When these neurons were made non-functional, the mice remained in a state of calm, despite attempts by the researchers to induce stress and excitement. These findings suggest that signals about stress states are normally relayed from the breathing center to the rest of the brain. This is the first study to demonstrate a mechanism for how breathing directly impacts states of mind. Since the same brain regions exist in humans, there is reason to believe this may be true in humans as well.

The diagram depicts the pathway (in green) that directly connects the mouse brain’s breathing center to the rest of the brain. Image from the Krasnow lab via the Stanford Medicine News Room.

Additionally, the vagus nerve makes direct contact with the heart and has the ability to slow heart rate. The vagus nerve may also be able to directly suppress systemic inflammation by activating the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, halting a domino effect of inflammatory activity that involves the spleen. Some evidence for this connection has been found in rodent models, although it remains largely unaddressed in humans, except for the observation that if the vagus nerve is removed (called a vagotomy), then systemic inflammation increases [1].

Although additional research is needed in the field, many researchers and clinicians are now focusing on using technologies to stimulate the vagus nerve in patients to achieve positive outcomes such as reducing stress and inflammation. This could possibly benefit those with depression, asthma, cardiovascular disease, and inflammatory disorders, among others. Vagal nerve stimulation has also been shown to suppress epileptic seizures [3]. Over time, increased activation of the parasympathetic pathways could lead to changes in the physical structure of the brain that may allow for longer lasting benefits for patients.

Researchers remain optimistic about the powers of the breath. Future studies will undoubtedly aim to definitively show the mechanism connecting the breath to the mental and physical body.

References:

- Gerritsen RJS & Band GPH (2018). Breath of Life: The Respiratory Vagal Stimulation Model of Contemplative Activity. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00397

- Yackle K. et al., (2017). Breathing Control Center Neurons Promote Arousal in Mice. Science. doi: 10.1126/science.aai7984

- Scott E. Krahl (2012). Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Epilepsy: A Review of the Peripheral Mechanisms. doi: 4103/2152-7806.91610

Thank you for the great overview!

Some users therefore may be interested in the App HeartBreath (at the moment only available for iOS)

HeartBreath – Biofeedback, RSA, HRV and Breathing

…Did you know that your heart beats faster during inhalation and slower during exhalation AND did you know that this is good for you? The technical term is RSA (respiratory sinus arrhythmia).

Time for slow breathing…

HeartBreath is a biofeedback tool, that addresses exactly this relationship between breathing and heart rate. The app guides you through a simple slow-breathing exercise (with pictures and sounds), while detecting and displaying the intervals between your heartbeats. With 6-8 breaths you can determine your heart rate AND the variability of your heartbeats (measure of stress, fitness, biological age etc.). You can measure, train and evaluate your personal status. No additional hardware devices are needed.

http://www.heartbreath.app

Pingback: The Neuroscience of the Breath

Pingback: I Speak Yoga | The one reason healing should be a personal and global priority!

Pingback: A Better Mindfulness Meditation Practice in 3 Easy Steps: What Neuroscientist Really Thinks – A Chat With Stars

Pingback: Mindfulness as a treatment for anxiety | NeuWrite San Diego